Myingyan District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Myingyan District

Physical aspects

A dry zone District in the Meiktila Division of Upper Burma, lying between 20° 32' and 21° 46' N. and 94° 43' and 96° i' E., with an area of 3,137 square miles. On the west it is bounded by the Irrawaddy river, on the north by Sagaing District, on the east by Kyaukse and Meiktila, and on the south by Magwe District. It is an irregularly shaped stretch of arid country, about twice as long as it is broad, stretching ^soects^ south-west and north-east along the eastern bank of the Irrawaddy. Most of it is dry undulating plain-land, diversified by isolated hill masses. The more northerly of these clumps of upland are comparatively insignificant. Popa Hill, however, near the south-east corner, is a conspicuous eminence, forming the most noticeable feature of the District.

It is more or less conical in shape ; its origin is volcanic, and it has two peaks of almost equal height nearly 5,000 feet above sea-level. While the summit is bare, the lower slopes are covered with gardens, where fruit trees flourish, for owing to its position in the centre of the plains, Popa attracts and catches a Hberal rainfall. On the south and east of the main central cone are many spurs extending to the Pin valley and Meiktila. North of the peak rough and hilly ground extends to the Taungtha hills, which rise from the plain a few miles south of Myingyan town, and attain a height of nearly 2,000 feet. Other stretches of upland deserving of mention are the Taywindaing ridge traversing the Pagan subdivision in the south-west, and the Yondo, the Sekkyadaung, and the Mingun hills in the Myingyan and Natogyi townships, in the extreme north of the District on the borders of Sagaing.

The only river of importance is the Irrawaddy, which skirts the western border. Entering the District near Sameikkon in the north, it runs in a south-westerly direction for a few miles, then south till it reaches Myingyan town, where it makes a curve to the west, forming, just off Myingyan, a large island called Sinde, which, in the dry season, interposes several miles of sandbank between the steamer channel and the town. After passing this bend, the river again takes a south- westerly course till it reaches Nyaungu (Pagan). Here the channel turns south for a while, then again south-west to Sale, and finally south- east till the southern border of the District is reached.

In the channel are numerous fertile islands, on which tobacco, beans, rice, chillies, and miscellaneous crops are grown. Parts of these islands are washed away every year, and fresh islands spring up in their place, a source of endless disputes among the neighbouring thugyis. Besides the Irrawaddy, the only perennial streams are the Popa chaung in the south and the Hngetpyawaing chaung in the north. Only the first of these, however, has an appreciable economic value. The principal intermittent watercourses are the Sindewa, the Pyaungbya, and the Sunlun streams. For the greater part of the year the beds of these are dry sandy channels, but after a heavy fall of rain they are converted into raging torrents.

The rocks exposed belong entirely to the Tertiary system, and consist for the most part of soft sandstones of pliocene age thrown into long flat undulations or anticlines by lateral pressure. In some instances denudation has removed the pliocene strata from the crests of the more compressed folds, and exposed the miocene clays and sandstones beneath. These low ridges are separated by broad tracts covered with alluvium. The clay varies in consistency, but is generally light and always friable on the surface, however hard it may be below.

The sandstone is of light yellow colour. It forms thick beds, which frequently contain nodular or kidney-shaped concretions of extremely hard siliceous sandstone. The concretions, which are sometimes of considerable size, are arranged in strings parallel to the bedding, and project out of the surrounding softer materials, forming a very con- spicuous feature in the landscape. In parts of the District, chiefly in the south, silicified trunks of trees are found, some of great length. Distinct from the rocks found in the plains is the volcanic Popa region. Dr. Blanford, in 1862, reported that he found six different beds represented on the hill and in its environs, which were as follows : lava of variable thickness capping the whole ; soft sands and sandy clays, yellow, greenish, and micaceous ; a white sandy bed, abounding in fragments of pumice ; volcanic ash, containing quartz and pebbles 3 ferruginous gravel and sandy clay, containing quartz and pebbles and numerous concretions of peroxide of iron ; coarse sand, mostly yellowish, with white specks.

The cutch-tree is found throughout the District, but it is fast dis- appearing. Not only is it cut and its very roots dug out of the ground to be boiled down for cutch, but the young trees are much exploited for harrow teeth. The thitya {Shorea obtusd), tanaung {^Acacia leuco- phloea), letpan {Bombax malabaricuni), nyaung (Ficiis), and tamarind {Tamarindus indica) are the commonest trees. Toddy-palms {Borassus flabellifer) are very plentiful, and form an appreciable part of the wealth of the people. Bamboos are found on the low hills on the Meiktila border and on Popa. The jack-tree {Artocarpus integrifolia) is common about Popa, and the zibyn {Cicea macrocarpd) and the zi {Zizyphiis Jiijuba) produce fruit which is exported by the ton to Lower Burma, besides being consumed in the District itself. On Popa a little teak and a number of thitya and tngyin {^Pentacme sianietisis) trees are found. Barely fifty years have elapsed since elephants, sdmbar, and tigers roamed the forests in the neighbourhood of Popa. Since the occupa- tion of Upper Burma, however, no elephants have visited the District, and the sdmbar and tiger have disappeared, though there are still numerous leopards, and on Popa a few specimens of the serow {Nemorhaedus sumatrensis) have been seen and shot. The thamin (brow-antlered deer) is scarce, but hog and barking deer are common, the former in the heavier jungle, the latter everywhere. Wild dogs, which hunt in packs, are found in the Natogyi and Kyaukpadaung townships.

The climate of the District is dry and healthy, the atmosphere being practically free from moisture for the greater part of the year. In March and April, and often for several days together throughout the rains, a strong, high, dry, south-west wind sweeps the District, a trial to human beings and a curse to the crops. Popa, thanks to its elevation, has a pleasantly cool cUmate during the hot season, but has never been systematically made use of as a sanitarium. The maximum tempera- ture in the Irrawaddy valley varied in 1901 from 105° in May to 85" in December, and the minimum from 75° in May to 56° in December. In July, a typical rains month, the mean was about 80° in the same year.

Owing to its position in the dry zone, the District suffers from a fickle and scanty rainfall. An excessively heavy downpour is often followed by a lengthy spell of dry scorching heat ; and it may be said that not much oftener than twice in the year on an average does the sky become black, and true monsoon conditions prevail. At other times the rainfall is confined to small showers and thunderstorms. It is, moreover, not only meagre, but capricious in its course, and leaves tracts here and there altogether unvisited. The rainfall in 1901, which was on the whole normal, varied from 2 2-| inches at Pagan and Sale to 30 inches in the more hilly townships of Taungtha and Kyaukpadaung.

History

The early history of the District is bound up with that of the famous Pagan dynasty, the beginnings of which are wrapped in a mist of nebulous tradition. According to legend, the king- dom of Pagan was founded early in the second century by Thamudarit, the nephew of a king of Prome, when that town was destroyed by the Talaings. This monarch is said to have established his capital at Pugama near Nyaungu, and to have been followed by kings who reigned at Pugama, Thiripyitsaya, Tampawadi, and Paukkarama (or Pagan) for nearly 1,200 years. One of the most famous of these early rulers was Thinga Yaza, who threw off the yellow robe of the pongyi and seized the throne, and is credited with having left a mark in history by his establishment of the Burmese era, starting in A.D. 638. The whole history of this early period, however, is unre- liable. Pagan itself is said to have been founded in 847 by a later king, Pyinbya ; and here we have evidence from other sources, which more or less corroborates the date given. The Prome chronicles record a second destruction of Prome by the Talaings in 742, which led to the migration of the reigning house northwards to Pagan.

Prome was in all probability raided several times in these early days, and even the later of the two sackings alluded to occurred at a period which can hardly be dignified with the title of historical. The early annals are of little scientific value, but from the accumulated mass of myth and tradition there emerge the two facts that the Pagan dynasty originated from Prome, and that it was finally established in the seats it was to make famous not later than the middle of the ninth century. The son and successor of Pyinbya, the founder of Pagan, was murdered by one of his grooms, a scion of the royal family, who succeeded him.

One of the murdered king's wives, however, escaped and gave birth to a son, who eventually regained the throne and became the father of Anawrata. This great ruler conquered Thaton, and from the sack of the Taking capital brought away the king Manuha and a host of captive artificers, whom he employed in building tlie pagodas for which Pagan has been famous ever since. He died after a reign of forty- two years. His great-grandson, Alaungsithu, extended his sway over Arakan and reigned seventy-five years ; he was succeeded by the cruel Narathu, who was assassinated by hired Indian bravoes, and was known afterwards as the Kalakya iiiiii ('the king overthrown by the foreigners '). While Narapadisithu, one of the last-named monarch's successors, was on the throne the kingdom attained the zenith of its glory, to crumble rapidly in the thirteenth century during the reign of Tayokpyemin, a monarch who earned his title by flying from Pagan before a Chinese invasion which he had brought on his country by the murder of an ambassador. The last king, Kyawzwa, was enticed to a monastery by the three sons of Theingabo, a powerful Shan Sawbwa, who compelled him to assume the yellow robe, and divided among themselves the residue of the Pagan kingdom. Since that time Pagan lias played a comparatively unimportant part in Burmese history. Yandabo, where the treaty was signed in 1826 which put an end to the first Burmese ^^'ar, lies on the Irrawaddy in the north of the District.

A District, with its head-quarters at Myingyan, was constituted in 1885 as the Mandalay expedition passed up the Irrawaddy, and Pagan was made the head-quarters of a second Deputy-Commissioner's charge. These two Districts contained, in addition to the areas now forming Myingyan, portions of Meiktila and INIagwe, and the whole of what is now Pakokku District ; but Pakokku and Meiktila were shortly afterwards formed, and on the creation of the former Pagan was incorporated in Myingyan. At annexation the local officials sur- rendered to the expedition, and there was no open hostility. The Burmese governor, however, after remaining loyal for six months, joined the Shwegyobyu pretender at Pakangyi in Pakokku District. During these early days of British dominion trade flourished on the river bank, but throughout 1886 portions of the District were practically held by dacoits, especially in the tract south of Pagan.

The northern and eastern areas, however, were kept quiet to a certain extent by the establishment of posts at Sameikkon on the Irrawadd}', and at Natogyi inland in the north-east of the District ; and combined operations from Myingyan and Ava put a stop to the depredations of a leader who called himself Thlnga Yaza. But the mountain valleys about the base of Popa long remained the refuge of cattle-lifters, robbers, and receivers of stolen property, and at least one dacoit was still at large in this tract ten years after annexation. In 1887 a leader named Nga Cho gave considerable trouble in the south, and a second outlaw, Nga Tok, harried the north. The latter was killed in 1888 ; but the former and another leader, Van Nyun, famous for his cruelties, disturbed the Dis- trict for two years more. By 18S9 the whole of Myingyan, excepting the Popa tract, wa.s free from dacoits ; but it was not till 1890, when Van Nyun surrendered, that the entire District could be regarded as pacified. Nga Cho remained at large six years longer, but ceased to be a dangerous leader when Yan Nyun came in.

The chief objects of archaeological interest are the ruined temples of Pagan. In the Natogyi township, at Pyinzi, are the ruins of a moat and wall said to mark the site of the residence of a prosperous prince of olden days. In the Taungtha township, at Konpato, is the Pato pagoda, where a large festival is held every November. Near East Nyaungu is the Kyaukku, or rock-cave pagoda, said to have been built to commemorate the floating of a stone which a pongyi, charged with a breach of his monastic vows, flung into the river, establishing his innocence by means of the miracle. In the cliff under the pagoda are several caves inhabited hy pongy is : and near them are the caves of the Hngetpyittaung kyaiing, reputed to have been built for Buddhist mis- sionaries from India, and to be connected by an underground passage with the Kyaukku pagoda, more than a mile distant. Festivals are held in November at the Zedigyi pagoda at Sale : in February at the Thegehla pagoda at Pakannge, in the Sale township; in November at the Myatshweku pagoda at Kyaukpadaung ; and in July at the Shinbinsagyo pagoda at Uyin, in the Sale township.

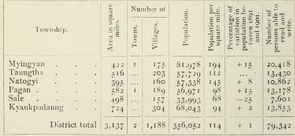

The population was 351,465 in 1891, and 356,052 in 1901. Its distribution in the latter year is shown in the tabic below : —

The two towns are Myingyan, the head-quarters, and Nyaungu. The population has been almost stationary for several years past, and has increa.sed materially only in the rather thinly inhabited township of Pagan. Elsewhere there has been a decrease, or the rise has been insignificant. Partial famines, due to scarcity of rain, have caused considerable emigration from the .Sale township, and similar causes have operated elsewhere. A regular ebb and flow of population between the Districts of Meiktila, ^'amcthin, and Myingyan is regu- lated largely b)- the barometer, but, owing to the absence of railways in Myingyan till lately, the inward flow in the more promising seasons has been checked. Though its rate of growth has been slow, Myingyan ranks high among the Districts of Upper Burma in density of popula- tion, and the rural population of the Myingyan township is as thick as in many of the delta areas. Buddhism is the prevailing religion ; in fact, the adherents of other religions form less than i per cent, of the total, and all but a fraction of the inhabitants speak Burmese.

The number of Burmans in 1901 was 354,100, or more tlian 99 per cent, of the total population. The District is one of the few in Burma that has no non-Burman indigenous races ; and the absence till recently of a railway is doubtless responsible for the smallness of the Indian colony, which numbers only about 1,400, equally divided between Hindus and Musalmans. In 1901 the number of persons directly dependent on agriculture was 224,095, representing 63 per cent, of the total population, compared with 66, the corresponding percentage for the Province as a whole.

There are only 180 Christians, 109 of whom are natives, and there is at present comparatively little active missionary work.

Agriculture

Myingyan is, for the most part, a stretch of rolling hills, sparsely covered with stunted vegetation, and cut up by deep nullahs ; and most of the cultivation is found in the long and generally narrow valleys separating the ridges, and on the lower slopes of the rising ground. The cultivated areas occur in patches. Rich land is scarce, the rainfall is precarious, and one of the main characteristics of the country is the large extent of ya or ' dry upland ' cultivation. The District may be divided for agricultural purposes into four tracts — alluvial, upland, valley, and the Popa hill area— while the crops grown on these may be split up into the following seven groups : permanently irrigated rice, mayin rice, mogaiing rice, ya crops, kaing crops, taze crops, and gardens. Both kaing and taze crops are grown on inundated land in the river-side area. The 'dry crops,' which are of the ordinary kinds (millet, sesamum, and the like), are found away from the Irrawaddy.

Some little distance from the river is a strip of poor land running north and south through the west of the Myingyan and Taungtha townships and the east of the Kyauk- padaung township, mainly devoted to the cultivation of millet, with sesamum and pulse as subordinate crops, often as separate harvests on one holding. South-west of this strip, and separated from it by the mass of Popa and the hills branching from it, is the poorest land in the District, occupying the greater part of the Pagan and Sale townships. The staple crop here is early sesamum, followed, as a second harvest, by peas, beans, or lu.

The uplands occupying the northern portion of the Myingyan township, the western portion of the Natogyi township, and the eastern portion of Taungtha township form, with the adjoining parts of Sagaing and Meiktila, the great cotton-growing tract of Burma, about 200 square miles in extent, nearly half of which lies within Myingyan. Mogaung (rain-irrigated) rice lands are cultivated in the east of the Natogyi township in the extreme north-east of the District, while mayin is grown in the beds of tanks, and the lower slopes of Popa are covered with plantain groves. The soil in the two richest townships (Natogyi and Myingyan) is loam and clay, and the rainfall is more regular here than in the poorest townships (Sale and Pagan), where gravel and sandstone predominate.

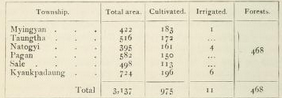

The following table gives the chief agricultural statistics for 1903-4, in square miles : —

Nearly 140 square miles of the area cultivated in 1903-4 bore

two harvests, and about 128 square miles failed to mature. In the

same year millet covered about 420, and sesamum (chiefly the early

variety) 336 square miles. Pulse of various kinds was grown on

137, and rice on only 81 square miles, an area quite insufficient for

the needs of the District. Cotton covered 88 square miles, and

1,900 acres were under orchards, the greater part being plantain groves.

Repairs to the Kanna tank have added 4,000 acres to the rice lands in the Natogyi township, but elsewhere the cultivable area has slightly decreased of late, in consequence of the formation of ' reserved ' forests. The only new crop that has met with success is the Pondi- cherry ground-nut, which was introduced a few years ago. In 1903-4 about 800 acres of land were under this crop. It gives a large out- turn and is very remunerative. The experimental cultivation of Havana and ^'irginia tobacco has not met with success. The leaves of these varieties are looked upon as too small, and the Burmans decline to take the trouble to cure them after American methods.

Practically no advances have been made under the Land Improve- ment Loans Act. On the other hand, advances under the Agriculturists' Loans Act, for the purchase of seed-grain and plough cattle, are very popular. The advances, which averaged more than Rs. 25,000 in the three years ending 1904, are made on the mutual securit)' of the villagers requiring loans ; their recovery on due date is easil)' efiected, and no loss has been (^aused to the state by any failure in repayment.

The District has always been noted for its bullocks, whose quality is due to the large areas of pasturage that exist on lands not fertile enough for cultivation, or only occasionally cultivated. Cattle-breeding is practised by all the well-to-do cultivators to a greater or less extent. Goat-breeding has largely increased of late. Buffaloes are kept along the banks of the Irrawaddy, but are rare in the interior. A few sheep are reared in Myingyan town by butchers. Myingyan has always held a high place among the pony-breeding centres of Burma ; and locally ihe palm is awarded to Popa by the Burmans, who credit Popa grass and water with special strength-giving properties, and have given the local breed the name of kyauksaung-myo. The necessity of allotting grazing-grounds has not yet arisen, for on the uplands there is abun- dance of waste land. Inland, away from the Irrawaddy, the question of watering the live-stock is often a difficult one.

Except in the basin of the Pin stream, which supplies a few private canals, there is practically no irrigation beyond what is afforded by tanks entirely dependent on the rainfall or high river-floods. The majority of these are in the north-east of the District, and the most important are the Kanna and the Pyogan. In 1 901-2 the newly repaired Kanna tank began to water the fields below it, with the result that land, which used formerly to be cultivated but had dropped out of cultivation, is now being eagerly taken up. It is estimated to be capable of irrigating 4,000 acres. The dam was seriously breached in 1903, but has been repaired. The Pyogan tank irri- gates about 1,000 acres. In the neighbourhood of Pyinzi, in the Natogyi township, a number of private tanks water a considerable area ; but in the whole District only 6,800 acres were returned as irrigated in 1903-4. Of this area, 2,900 acres drew their supplies from Government works.

In 1901 the District contained 73 fisheries, of which 57 were in the Myingyan and 16 in the Pagan township. The only important one is the Daung, which lies about 5 miles to the south-west of Myingyan town, and dries up enough to produce ffiayi?i rice from November to April. A large number of the fishermen leave the District annually at the end of November for the delta Districts and Katha, returning to Myingyan when the rains set in.

With the exception of a tract in the vicinity of Popa, the forests of Myingyan consist chiefly of dry scrub growth. Here the only plant of any importance is the Acacia Catechu, yielding the cutch of commerce. The cutch industry used to be flourishing, but has de- clined of late years owing to the exhaustion of the supply, due to overwork in the past. Approaching Popa the scrub growth merj^es into dry forest with ingy'ui, and here and there thiiya and teak of poor description, while the old crater of Popa and the slopes on the south and east sides of the hill are clothed with evergreen forest. At the close of 1 900-1 there were no 'reserved' forests in the Dis- trict, but since then 74 square miles have been gazetted as Reserves. The area of unreserved forests is 394 square miles ; but hardly any- thing of value is left in any of the jungle tracts, and the total forest revenue averages only about Rs. 600.

- Iron ore and sulphur have been found in the Pagan township, but are not worked. In several villages in the Kyaukpadaung township, and at Sadaung in the Natogyi township, salt is manufactured by primitive methods for local consumption. Petroleum oil has been found by the Burma Oil Company in the neighbourhood of Chauk village in the Singu circle of the Pagan township. The oil is said to be extraordinarily low-flashing, of a quality similar to that obtained from the Yenangyat wells. A refinery for extracting the naphtha has been built: and in 1903 the company was employing a staff of 7 Americans, 47 natives of India, and 55 Burmans. The Rangoon Oil Company is also boring within the limits of the District.

Trade and communication

Cotton-weaving is practised by women on a small scale in nearly every village, the yarn used being generally imported from England or Bombay. A few goldsmiths, who make orna- iraaeand ments for native wear, are found in the towns and large villages ; and at Mymgyan the mhabitants of one whole street devote their time to casting bells, images, and gongs from brass. Pottery is made at Yandabo and Kadaw in the Myingyan township, and in a few other localities, but only as an occupation subsidiary to agriculture. Lacquer-ware is manufactured by the people of Old Pagan, West Nyaungu, and the adjoining villages. The framework of the articles manufactured is composed of thin slips of bamboos closely plaited together. This is rubbed with a mixture of cow-dung and paddy husk to fill up the interstices, after which a coat of thick black varnish {tJiitsi) is laid on the surface. An iron style is then used to grave the lines, dots, and circles which form the pattern on the outer portion of the box. Several successive coats of cinnabar, yellow orpiment, indigo, and Indian ink are next put on, the box or other article being turned on a primitive lathe so as to rub off the colour not required in the pattern.

After each coat of colour has been applied, the article is polished by rubbing with oil and paddy husk. The workmen who apply the different colours are generally short-lived and liable to disease ; their gums are always spongy and discoloured. Mats and baskets are woven in the villages on Popa and in the neighbourhood, where bamboos grow plentifully. The principal factory is a cotton-ginning mill in Myingyan town owned by a Bombay firm. It is doing a large business, and buys up nearly three-fourths of the raw cotton grown in the District, having thus replaced the hand cotton-gins which existed in large numbers before its establishment. In addition to cotton- ginning, the mill extracts oil from cotton seed, and makes cotton-seed cake and country soap. Four other steam ginning factories have been established ; and keen competition has caused the prices of the raw material to rule high, and has greatly benefited the cultivators.

The external trade is monopolized by Myingyan town, Sameikkon, Taungtha, and Yonzin in the Myingyan, and by Xyaungu, Singu, Sale, and Kyaukye in the Pagan subdivision. The principal traders at Myingyan are Chinese and Indians, but elsewhere the Burmans still have most of the local business in their hands. The chief exports arc beans, gram, tobacco, cotton, jaggery, chillies, cutch, wild plums, lacquer-ware, hides, cattle, and ponies. Chief among the imports are rice, paddy, salt and salted fish, hardware, piece-goods, yarn, bamboos, timber, betel-nuts, and petroleum. The imports come in and the ex- ports go out by railway and steamer. Most of the business is done at the main trade centres, but professional pedlars also scour the whole District, hawking imported goods of all sorts among the rural population.

The branch railway line from 'I'hazi through Meiktila to Myingyan, commenced in 1897 as a famine relief work, has a length of about 32 miles within the District. The country is well provided with roads. Those maintained by the Public ^Vorks department have a length of 203 miles, the most important running from Myingyan to Mahlaing (31 miles), from Myingyan to Natogyi (19 miles), and on to Pyinzi near the Kyaukse boundary (15 miles), from Myingyan to Pagan (42 miles), from Pagan to Kyaukpadaung and I.etpabya, near the borders of Magwe District (50 miles), and from Kyaukpadaung to Sattein and Taungtha (45 miles). About 400 miles of serviceable fair-weather roads, rather more than one-third of which are in the Pagan township, are maintained by the District fund.

The only navigable river is the Irrawaddy, which forms the western border. The Irrawadd\- Flotilla Company's steamers (mail and cargo) call • at Myingyan, Sameikkon, Nyaungu, Singu, and. .Sale regularly sexeral times a week each way, and there are daily steamers from Myingyan to Mandalay and Pakokku. A large part of the trade of t-he riverain tract is carried in country boats. The District contains 19 public ferrie.s — two managed by the Myingyan municipality, one by the Nyaungu town committee, and 16 by the Deputy-Commissioner for the benefit of the Myingyan District fund.

Famine

The earliest famine still remembered occurred in 1856-7, when the rains are said to have failed completely and the crops withered in the fields. No steamers were available to bring up rice from Lower . Burma, nor was there any railway to carry emigrants

down ; the result was that the people died in the fields gnawing the bark of trees, or on the highways wandering in search of food, or miserably in their own homes. The more desperate formed themselves into gangs, and murdered, robbed, and plundered. The Burmese government imported rice from the delta, but its price rose to, and remained at, famine level. From the epoch of this famine changes came upon the country. It had brought home to the culti- vators the unreliability of rice ; and the next few years saw an increase in the area under sesamum, cotton, and bdjra, and the introduction of jowdr. The years preceding the annexation in 1S85 were bad, and in 189 1-2 there was distress. In 1896-7 the early rain did not fall, and the early sesamum, the most important crop in the District, failed completely. No rain fell in either August or September, the November showers never came to fill the ear, and famine resulted. Relief works were opened without delay, and the total number of units (in terms of one day) relieved from November, 1896, to November, 1897, was four and a half millions. Remissions of thathameda owing to the famine amounted to nearly 4 lakhs. A total of \\ lakhs was expended out of the Indian Charitable Relief Fund on aid to the sufferers, and nearly i lakh was spent in granting agricultural loans in 1896-7 and 1897-8. The total cost of the famine operations exceeded 11 lakhs. The most important relief work carried out was the Meiktila-Myingyan railway.

Administration

The District is divided for administrative purposes into two sub- divisions : Myingyan, comprising the Mvingvax, Tauxgtha, and Natogvi township ; and Pagan, comprising the Administration. Pagan, Sale, and Kvaukpadaung townships. These are staffed by the usual executive officers, under whom are 777 village headmen, 436 of whom draw commission on revenue collections. At head-quarters are an akunwim (in subordinate charge of the revenue),

a treasury ofificer, and a superintendent of land records, with a staff of 8 inspectors and 70 surveyors. The District forms a subdivision of the Meiktila Public Works division, and (with Meiktila and Kyaukse Districts the Kyaukse subdivision of the Mandalay Forest division.

The District, subdivisional, and township courts are as a rule presided over by the usual executive officers. An ofificer of the Provincial Civil Service is additional judge of the District court, spending half the month at Myingyan and half at Pakokku ; and the treasury ofificer, Myingyan, has been appointed additional judge of the Myingyan township court. The prevailing form of crime in the District is cattle-theft. Litigation is, on the whole, of the ordinary type.

In king Minclon's time tliathaineda was introduced into the District, and in 1S67 the rate is said to have been Rs. 3, while in the following year it rose to Rs. 5. 'l"he average seems to have fluctuated; but at the time of the British occupation it was nominally Rs. 10 per household, though the actual incidence was probably less than this. In addition to thathameda, royal land taxes were paid on islands, land known as konayadau>, and mayin fields. After annexation revenue was not as a rule assessed on may 171 rice land, but was paid on the other two classes of royal land — in the case of island land at acre rates (from 1892 onwards) ; in the case of konayada^v at a rate representing the money value of one-fourth of the gross produce. The only unusual tenure found in the District was that under which the kyedan or com- munal lands in 47 circles in the Pagan and Kyaukpadaung townships were held. In former days the people had the right to hold, but not to alienate, these lands, and any person who left the circle forfeited the right to his holding. No rents were paid to the crown for the land, but military service had to be performed if required. The District was brought under summary settlement during the seasons 1 899-1 901, and in 1 901-2 the former land revenue system was superseded by the arrangement now in force. Under this, the rates on non-state rice land vary from 15 annas per acre on mogaung to Rs. 3 on irrigated rice ; on state lands the rate is a third as much again. On ya land the minimum is 4 annas and the maximum Rs. 1-4 per acre, and non-state land is assessed at the same rate as state land. The assess- ment on orchards varies from Rs. 1-14 on non-state plantain groves in the plains to Rs. 20 on state betel vineyards. Plantains on Popa pay Rs. 3 or Rs. 4 per acre, according as they are on non-state or state land : and all other garden crops (mangoes, jacks, toddy-palms, (See.) pay Rs. 3, whatever the nature of the land. On riverain bobaba'nig land (kaing or taze) rates vary from Rs. 1-8 for the least valuable crops to Rs. 5-4 for onions and sweet potatoes, the state land rates being one-third higher. If an area is twice cropped, only the more valuable crop is assessed. The f/iathameda rate per household was reduced from Rs. 10 to Rs. 3 in 190 1.

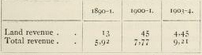

The growth of the revenue since 1 890-1 is shown in the following table, in thousands of rupees : —

Until the introduction of settlement rates, thathameda was by far the most important source of revenue in the District. It fell from Rs. 6,40,000 in 1900-1 to Rs. 2,23,000 in 1903-4.

The income of the District fund in 1903-4 was Rs. 17,200, which is devoted mainly to public works. There is one municipality, Myin- GYAN. Pagan was formerly a municipality, but in 1903 a body known as the Nyaungu town committee took the place of the municipal committee.

The District Superintendent of police has under him 2 Assistant Superintendents (in charge of the Myingyan and Pagan subdivisions), 2 inspectors, 13 head constables, 38 sergeants, and 397 constables, distributed in ii stations and 15 outposts. The military police belong to the Mandalay battalion, and their sanctioned .strength Is 205 of all ranks, of whom 145 are stationed at Myingyan, 30 at Nyaungu, and 30 at Kyaukpadaung.

A Central jail is maintained at Myingyan, and a District jail, mainly for leper prisoners, at Pagan. The Myingyan jail has accommodation for 1,322 prisoners, who do wheat-grinding, carpentry, blacksmith's work, cane-work, and weaving and gardening. The Pagan jail contains about 60 convicts, half of them lepers. In the leper section only the lightest of industries are carried on ; in the non-leper section the usual jail labour is enforced.

Owing, no doubt, to its large proportion of Burmans, Myingyan showed in 1901 a fair percentage of literate persons — 45 in the case of males, 2-4 in that of females, and 22 for both sexes together. In 1904, 5 special, 14 secondary, iii primary, and 1,145 elementary (private) schools were maintained, with an attendance of 17,724 pupils (in- cluding 1,037 girls). The total has been rising steadily, having been 7,539 in 1891 and 15,121 in 1901. The expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 15,300, of which Provincial funds provided Rs. 12,100, while Rs. 3,100 was contributed by fees.

There are three hospitals with a total of 63 beds, and two dis- pensaries. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 23,272, including 702 in-patients, and 626 operations were performed. The joint income of the institutions amounted to Rs. 12,100, towards which municipal and town funds contributed Rs. 6,800 : Provincial funds, Rs. 3,800 ; the District fund, Rs. 600 ; and private sub.scribers, Rs. 800.

Vaccination is compulsory in the towns of Myingyan and Nyaungu. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated .was 10,776, representing 30 per 1,000 of population.

[B. S. Carey, Seffkme/if Reporf 1901