Mysore District

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

District in the south of the State of Mysore

District in the south of the State of Mysore, lying between 11° 36' and 13° 3' N. and 75° 55' and 77° 20' E., with an area of 5,496 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Hassan and Tumkūr Districts ; on the east by Bangalore and the Coimbatore District of Madras ; on the south by the Nīlgiri and Malabar Districts of Madras ; and on the west by Coorg.

The river Cauvery, besides forming the boundary for some distance both on the west and east, traverses the District from north-west to east, receiving as tributaries the Hemāvati, Lokapāvani, and Shimsha on the north, and the Lakshmantīrtha, Kabbani, and Honnu-hole or Suvarnāvati on the south. Lofty mountain ranges covered with vast forests, the home [S. 251] of the elephant, shut in the western, southern, and some parts of the eastern frontier.

The only break in this mighty barrier is in the southeast, where the Cauvery takes its course towards the lowlands and hurls itself down the Cauvery Falls, called Gagana Chukki and Bhar Chukki, at the island of Sivasamudram. The principal range of hills within the District is the Biligiri-Rangan in the south-east, rising to 5,091 feet above the level of the sea. Next to these, the isolated hills of Gopālswāmi in the south (4,770 feet), and of Bettadpur in the north-west (4,389 feet), are the most prominent heights, with the Chāmundi hill (3,489 feet) to the south-east of Mysore city.

The French Rocks (2,882 feet), north of Seringapatam, are conspicuous points of a line culminating in the sacred peak of Melukote (3,579 feet). Short ranges of low hills appear along the south, especially in the south-west. On the east are encountered the hills which separate the valleys of the Shimsha and Arkāvati, among which Kabbāldurga (3,507 feet) has gained an unenviable notoriety for unhealthiness.

Mysore District may be described as an undulating table-land, fertile and well watered by perennial rivers, whose waters, dammed by noble and ancient anicuts, enrich their banks by means of canals. Here and there granite rocks rise from the plain, which is otherwise unbroken and well wooded.

The extreme south forms a tarai of dense and valuable but unhealthy forest, occupying the depression which runs along the foot of the Nīlgiri mountains. The lowest part of this is the remarkable long, steep, trench-like ravine, sometimes called the Mysore Ditch, which forms the boundary on this side, and in which flows the Moyār.

The irrigated fields, supplied by the numerous channels drawn from the Cauvery and its tributaries, cover many parts with rich verdure. Within this District alone there are twenty-seven dams, the channels drawn from which have a total length of 807 miles, yielding a revenue of 5 1/3 lakhs.

The geological formation is principally of granite, gneiss, quartz, and hornblende. In many places these strata are overlaid with laterite. Stone for masonry, principally common granite, is abundant throughout the District. Black hornblende of inferior quality and potstone are also found. Quartz is plentiful, and is chiefly used for road-metalling. Dikes of felsites and porphyries occur abundantly in the neighbourhood of Seringapatam, and a few elsewhere. They vary from fine-grained hornstones to porphyries containing numerous phenocrysts of white to pink felspar, in a matrix which may be pale green, pink, red, brown, or almost black.

The majority of the porphyries form handsome building stones, and some have been made use of in the new palace at Mysore. Corundum occurs in the Hunsūr tāluk. In Singaramāranhalli the corundum beds were found to be associated with an intrusion of olivine-bearing rocks, similar to those of the Chalk Hills near Salem, [S. 252] and large masses of a rock composed of a highly ferriferous enstatite, with magnetite and iron-alumina spinel or hercynite.

The trees in the extensive forest tract along the southern and western boundary are not only rich in species, but attain a large size. Of teak (Tectona grandis) there are several large plantations. Other trees include Shorea Talura, Pterocarpus Marsupium, Terminalia tomentosa, Lagerstroemia lanceolata, and Anogeissus latifolia, which are conspicuous and very abundant in the Muddamullai forest.

In February most of these trees are bare of leaf, and represent the deciduous belt. In open glades skirting the forests and descending the Bhandipur ghāt are plants of a varied description. Bambusa arundinacea occurs in beautiful clumps at frequent intervals. There are also Helicteres Isora, Hibiscus Abelmoschus, and many others. Capparis grandiflora is most attractive in the Bhandipur forest, and there is also a species without thorns. Clusters of parasites, such as Viscum orientale, hang from many trees.

On the Karabi-kanave range farther north the grasses Andropogon pertusus and Anthistiria ciliata attain an abnormal size, and are often difficult to penetrate. Ferns, mosses, and lichens are abundant in the rainy season. There are also a few orchids. The heaviest forest jungle is about Kākankote in the south-west. The Biligiri-Rangan range in the south-east possesses an interesting flora with special features. The growth includes sandalwood, satin-wood (Chloroxylon Swietenia), Polyalthia cerasoides, and others.

The babūl (Acacia arabica) attracts attention by the road-side and in cultivated fields. Hedgerows of Euphorbia Tirucalli, Jatropha Curcas, and Vitex Negundo are not uncommon. In the poorest scrub tracts Phoenix farinifera is often gregarious. The growth in the parks at Mysore city is not so luxuriant as at Bangalore, where the soil is richer; but in the matter of species it is much the same.

The flora of Chāmundi, which is a stony hill, is limited in species and poor in growth. Clinging to the rivers and canals are found such plants as Crinum zeylanica, Salix tetrasperma, and Pandanus odoratissimus.

Mysore: Temperature

The mean temperature and diurnal range at Mysore city in January are 73° and 25°; in May, 81° and 23°; in July, 75° and 16°; in November, 73° and 18°. The climate is generally healthy, but intermittent fevers prevail during the cold months. The annual rainfall averages 33 inches. The wettest month is October, with a fall of 8 inches ; then May, with 6 ; and next September, with 5 inches.

The earliest traditional knowledge we have relating to this District goes back to the time of the Maurya emperor, Chandra Gupta, in the fourth century B. C. At that time a State named Punnāta occupied the south-west. After the death of Bhadrabāhu at Sravana Belgola, the Jain emigrants whom he had led from Ujjain in the north, Chandra Gupta being his chief disciple, [S. 253] passed on to this tract.

It is mentioned by Ptolemy, and its capital Kitthipura has been identified with Kittūr on the Kabbani, in the Heggadadevankote tāluk. The next mention concerns Asoka, who is said to have sent Buddhist missionaries in 245 B. C. to Vanavāsi on the north-west of the State, and to Mahisa-mandala, which undoubtedly means the Mysore country. After the rise of the Ganga power, their capital was established in the third century A. A. at Talakād on the Cauvery.

They are said to have had an earlier capital, at Skandapura, supposed to be Gazalhatti, on the Moyār, near its junction with the Bhavāni ; but this is doubtful. In the fifth century the Ganga king married the Punnāta king's daughter, and Punnāta was soon after absorbed into the Ganga kingdom. In the eighth century the Rāshtrakūtas overcame and imprisoned the Ganga king, appointing their own viceroys over his territories. But he was eventually restored, and intermarriages took place between the two families.

In the tenth century the Ganga king assisted the Rāshtrakūtas in their war with the Cholas. In 1004 the Cholas invaded Mysore under Rājendra Chola, and, capturing Talakād, brought the Ganga power to an end. They subdued all the country up to the Cauvery, from Coorg in the west to Seringapatam in the east, and gave to this District the name Mudikondacholamandalam.

Meanwhile the Hoysalas had risen to power in the Western Ghāts, and made Dorasamudra (Halebīd in Hassan District) their capital. About 1116 the Hoysala king, Vishnuvardhana, took Talakād and expelled the Cholas from all parts of Mysore. He had been converted from the Jain faith by the Vaishnava reformer Rāmānuja, and bestowed upon him the Ashtagrāma or 'eight townships,' with all the lands north and south of the Cauvery near Seringapatam.

The Hoysalas remained the dominant power till the fourteenth century. The Muhammadans from the north then captured and destroyed Dorasamudra, and the king retired at first to Tondanūr (Tonnūr, north of Seringapatam). But in 1336 was established the Vijayanagar empire, which speedily became paramount throughout the South. One of the Sāluva family, from whom the short-lived second dynasty arose, is said to have built the great temple at Seringapatam.

But Narasinga, the founder of the Narasinga or third dynasty, seized Seringapatam about 1495 by damming the Cauvery and crossing over it when in full flood. Later on, Ganga Rājā, the Ummattūr chief, rebelled at Sivasamudram and was put down by Krishna Rāya, in 1511. Eventually the Mysore country was administered for Vijayanagar by a viceroy called the Srī Ranga Rāyal, the seat of whose government was at Seringapatam. Among the feudal estates under his control in this part were Mysore, Kalale, and Ummattūr in the south, and the Changālva kingdom in the west. After the overthrow of Vijayanagar by the Muhammadans [S. 254] in 1565, the viceroy's authority declined, and the feudatories began to assume independence. At length in 1610 he retired, broken down in health, to die at Talakād, and Rājā Wodeyar of Mysore gained possession of Seringapatam.

This now became the Mysore capital, and the lesser estates to the south were absorbed into the Mysore kingdom. Seringapatam was several times besieged by various enemies, but without success. From 1761 to 1799 the Mysore throne was held by the Muhammadan usurpers, Haidar Alī and Tipū Sultān.

During this period several wars took place with the British, in the course of which Haidar Alī died and finally Tipū Sultān was killed. The Mysore family was then restored to power by the British, and Mysore again became the capital in place of Seringapatam. Owing to continuous misrule, resulting in a rebellion of the people, the Mysore Rājā was deposed in 1831 and the country administered by a British Commission. This continued till 1881, when Mysore was again entrusted, under suitable guarantees, to the ancient Hindu dynasty.

Of architectural monuments the principal one is the Somnāthpur temple, the best existing complete example of the Chālukyan style. It was built in 1269, under the Hoysalas. It is a triple temple, and Fergusson considered the sculpture to be more perfect than at Belūr and Halebīd. Other notable examples of the same style are the temples at Basarālu, built in 1235, and one at Kikkeri, built in 1171.

The tall pillars of the temple in Agrahāra Bāchahalli are of interest. They are of the thirteenth century, and on the capital of each stands the figure of an elephant, with Garuda as the mahaut, and three or four people riding on it. As good examples of the Dravidian style may be mentioned the temples at Seringapatam, Nanjangūd, and on the Chāmundi hill. Of Muhammadan buildings the most noteworthy are the Gumbaz or mausoleum of Haidar and Tipū at Ganjam, and the Daryā Daulat summer palace at Seringapatam. Of the latter, Dr. Rees, who has travelled much in Persia and India, says :—

'The lavish decorations, which cover every inch of wall from first to last, from top to bottom, recall the palaces of Ispahān, and resemble nothing that I know in India.'

Attention may also be directed to the bridges of purely Hindu style and construction at Seringapatam and Sivasamudram. The numerous inscriptions of the District have been translated and published.

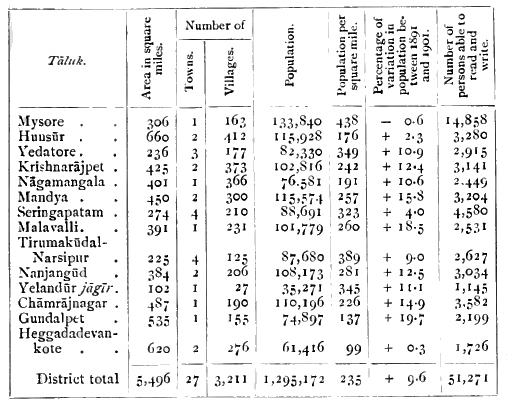

The population at each Census in the last thirty years was : (1871) 1,104,808, (1881) 1,032,658, (1891) 1,181,814, and (1901) 1,205,172. The decrease in 1881 was due to the famine of 1876-8. By religion, in 1901 there were 1,232,958 Hindus, 49,484 Musalmāns, 6,987 Animists, 3,707 Christians, 2,006 Jains, and 30 Parsīs. The density of population was 235 persons per square mile, that for the State being 185. The number of towns [S. 255] is 27, and of villages 3,212. Mysore, the chief town (population, 68,111), is the only place with more than 20,000 inhabitants.

The following table gives the principal statistics of population in 1901

The Wokkaligas or cultivators are the strongest caste in numbers, their total being 320,000. Next come the outcaste Holeyas and Mādigas, of whom there are 194,000 and 25,000; the Lingāyats, numbering 173,000; Kurubas or shepherds, 127,000; Besta or fishermen, 10,200. The total of Brāhmans is 43,000. Among Musalmāns, the Sharīf's form nearly seven-tenths, being 29,000.

The nomad Korama number 2,500; wild Kuruba, 2,300; and Iruliga, 1,600. About 74 per cent. of the total are engaged in agriculture and pasture; 8 per cent, each in unskilled labour not agricultural, and in the preparation and supply of material substances; 2.5 per cent. in the State service, and 2.4 per cent. in personal services; 1.9 per cent. in commerce, transport, and storage ; and 1.8 per cent. in professions.

Christians in the District

The Christians in the District number 3,700, of whom 2,200 are in Mysore city. The total includes 3,300 natives. Early in the eighteenth century a Roman Catholic chapel was built at Heggadadevankote, but the priest was beaten to death by the people. A chapel at Seringapatam, which was courageously defended by the Christian troops, escaped the destruction of all Christian churches ordered by Tipū Sultān.

After the downfall of the latter in 1799, the well-known Abbé Dubois took charge, and founded the mission at Mysore, where large churches, schools, and convents arc in existence. The London [S. 256] and Wesleyan Missions began work at Mysore in 1839, but the former retired in 1850. The Wesleyans have churches, a college, schools for boys and girls, and a printing press, and are building a large hospital for women and children.

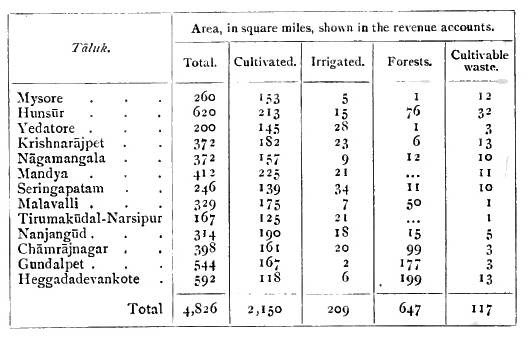

Red soil prevails throughout the District, while one of the most valuable tracts of the more fertile black soil in the country runs through the south-east in the Chāmrājnagar tāluk and the Yelandūr jāgīr. The following table gives statistics of cultivation in 1903-4 :—

The crops, both 'wet' and 'dry,' are classed under two heads, according to the season in which they are grown, hain and kār. The season for sowing both 'wet' and 'dry' hain crops opens in July, that for sowing kār 'wet crops' in September, and for kār 'dry crops' in April. It is only near a few rain-fed tanks in the east that both hain and kār crops are now obtained from the same 'wet' lands in the year. On 'dry' lands it is usual to grow two crops in the year, the second being a minor grain, if the land is fertile enough to bear it.

But of grains which form the staple food, such as rāgi and jola, the land will only produce one crop as a rule, and consequently the ryots arc obliged to choose between a hain or kār crop. In the north the former is preferred, because the growth is there more influenced by the monsoon. But in the south a kār crop is found more suitable, because the springs and frequent rain afford a tolerable supply of water all the year round, whereas the south-west monsoon, which falls with greater force on the forest land, would render ploughing in June laborious. Rāgi in 1903-4 occupied 873 square miles; gram, 521 ; other food-grains, 360; rice, 184; oilseeds, 159; garden produce, 27; sugar-cane, 10.

Coffee cultivation has been tried, the most successful being in the [S. 257] Biligiri-Rangan region. Much attention has been paid to mulberry cultivation in the east, in connexion with the rearing of silkworms. During the twelve years ending 1904 Rs. 29,000 was advanced as agricultural loans for land improvement, and Rs. 16,500 for field embankments.

The area irrigated from canals is 122 square miles, from tanks and wells 72, and from other sources 15. The length of channels drawn from rivers is 807 miles, and the number of tanks 1,834, of which 157 are classed as 'major.'

The south and west are occupied by continuous heavy forest, described in the paragraph on Botany. The State forests in 1904 covered an area of 521 square miles, 'reserved' lands 81, and plantations 8. Teak, sandal-wood, and bamboos, with other kinds of timber, are the chief sources of forest revenue. The forest receipts in 1903-4 amounted to nearly 5 lakhs.

Gold-mining, experimentally begun at the Amble and Wolagere blocks near Nanjangūd, has been abandoned. Prospecting for gold has also been tried near Bannūr. Iron abounds in the rocky hills throughout the District, but is worked only in the Heggadadevankote and Malavalli tāluks. The iron of Malavalli is considered the best in the State. Stones containing magnetic iron are occasionally turned up by the ploughshare near Devanūr in the Nanjangūd tāluk.

Talc is found in several places, and is used for putting a gloss on baubles employed in ceremonies. It occupies the rents and small veins in decomposing quartz, but its laminae are not large enough to serve for other purposes. Asbestos is found in abundance in the Chāmrājnagar tāluk. Nodules of flint called chakmukki are found in the east, and were formerly used for gun-flints.

Cotton cloth, blankets, brass utensils, earthenware, and jaggery (unrefined sugar) from both cane and date, are the principal manufactures. There is also some silk-weaving. The best cloth is made at Mysore and Ganjam. At Hunsūr factories were formerly maintained in connexion with the Commissariat, consisting of a blanket factory, a tannery and leather factory, and a wood-yard where carts and wagons were built. Although these have been abolished, their influence in local manufactures remains. Nearly all the country carts of the District are made here.

There are also extensive coffee-works and saw-mills, under European management. The number of looms or small works reported for the District are: silk, 50; cotton, 4,267 ; wool, 2,400; other fibres, 862; wood, 200 ; iron, 360 ; oil-mills, 857 ; sugar and jaggery mills, 360.

A great demand exists for grain required on the west coast and in Coimbatore, and the Nīlgiri market derives a portion of its supplies from this District. There is also considerable trade with Bangalore [S. 258] and Madras. Many of the traders are Musalmāns, and on the Nīlgiri road Lambānis are largely employed in trade. The large merchants, who live chiefly in Mysore city, are for the most part of the Kunchigar caste.

They employ agents throughout the District to buy up the grain, in many cases giving half the price in advance before the harvest is reaped. A few men with capital are thus able to some extent to regulate the market. Much of the trade of the country is carried on by means of weekly fairs, which are largely resorted to ; and at Chunchankatte in the Yedatore tāluk there is an annual fair which lasts for a month. Upon these the rural population are mainly dependent for supplies.

The most valuable exports are grain, oilseeds, sugar, and jaggery ; and the most valuable imports are silk cloths, rice, salt, piece-goods, ghī, cotton and cotton thread, and areca-nuts. The Mysore State Railway from Bangalore to Nanjangūd runs for 61 miles through the District from the north-east to the centre. The length of Provincial roads is 330 miles, and of District fund roads 539 miles.

The District is virtually secured against famine by the extensive system of irrigation canals drawn from the Cauvery and its tributaries. In 1900 some test works for relief were opened for a short time in the Mandya tāluk.

The District is divided into fourteen tāluks : Chāmrājnagar, Gundalpet, Heggadadevankote, Hunsūr, Krishnarājpet, Malavalli, Mandya, Mysore, Nāgamangala, Nanjangūd, Seringapatam, Tirumakūdal-Narsipur, Yedatore, and the Yelandūr jāgīf.

It is under a Deputy-Commissioner, and subject to his control the tāluks have been formed into the following groups in charge of Assistant Commissioners : Mysore, Seringapatam, Mandya, and Malavalli, with head-quarters at French Rocks ; Nāgamangala and Krishnarājpet, with head-quarters at Krishnarājpet ; Chāmrājnagar, Nanjangūd, Gundalpet, and Tirumakūdal-Narsipur, with head-quarters at Nanjangūd ; Heggadadevankote, Hunsūr, and Yedatore, with head-quarters at Mysore city.

There are District and Subordinate Judge's courts at Mysore city, whose jurisdiction extends over Hassan District, besides two Munsifs' courts; in addition, there are Munsifs at Seringapatam and Nanjangūd. Dacoity is not infrequent.

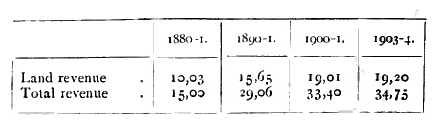

The land revenue and total revenue

The land revenue and total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees

[S. 259] The revenue survey and settlement were introduced in the west in 1884, in the north and east between 1886 and 1890, in the south between 1891 and 1896. The incidence of land revenue per acre of cultivated area in 1903-4 was Rs. 1-4-6. The average assessment per acre on 'dry' land is R. 0-12-1 (maximum scale Rs. 2-4, minimum scale R. 0-1); on 'wet' land, Rs. 5-3-11 (maximum scale Rs. 11, minimum scale R. 0-4); on garden land, Rs. 3-15-6 (maximum scale Rs. 15, minimum scale Rs. 1-8).

In 1903-4, besides the Mysore city municipal board, there were seventeen municipalities—Hunsūr, Chāmrājnagar, Yedatore, Heggadadevankote, Gundalpet, Nanjangūd, Tirumakūdal-Narsipur, Piriyāpatna, Bannūr, Talakād, Seringapatam, Mandya, Krishnarājpet, Malavalli, Nāgamangala, Melukote, and French Rocks—with a total income of Rs. 47,000, and an expenditure of Rs. 42,000 ; and also 8 village Unions, converted in 1904 from previously existing minor municipalities —Sargūr, Sosale, Sāligrāma, Mirle, Kalale, Maddūr, Pālhalli, and Kikkeri—with a total income and expenditure of Rs. 10,000 and Rs. 18,000.

Outside the municipal areas, local affairs are managed by the District and tāluk boards, which had an income of 1.5 lakhs in 1903-4 and spent 1.1 lakhs, including Rs. 86,000 on roads and buildings. The police force in 1903-4 included 2 superior officers, 181 subordinate officers, and 1,210 constables. Of these, 46 officers and 275 constables formed the city police ; and 3 officers and 49 constables the special reserve. The Mysore District jail has accommodation for 447 prisoners. The daily average in 1904 was 200. In the 14 lock-ups the average daily number of prisoners was 17.

The percentage of literate persons in 1901 was 20.1 for the city and 3.1 for the District (7.3 males and 0.6 females). The number of schools increased from 675 with 22,346 pupils in 1890-1 to 778 with 23,126 pupils in 1900-1. In 1903-4 there were 766 schools (458 public and 308 private), with 22,853 pupils, of whom 3,379 were girls.

Besides the general hospital at Mysore city, there are 23 dispensaries in the District, at which 250,000 patients were treated in 1904, of whom 2,300 were in-patients, the number of beds available being 69 for men and 60 for women. The total expenditure was Rs. 82,000.

The number of persons vaccinated in 1904 was 13,896, or 11 per 1,000 of the population.