North Indian Popular Religion: 16a-Animal-worship

This article is an extract from THE POPULAR RELIGION AND FOLK-LORE OF NORTHERN INDIA WESTMINSTER Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor |

North Indian Popular Religion: 16a-Animal-worship

ANIMAL-WORSHIP.

Τῶ δέ καὶ Αὐτομέδων ὕπαγε ζυγὸν ὠκέας ἵππους

Χάνθον καὶ Βαλίον, τὼ ἅμα πνοιῆσι πετέσθην

Τούς ἔτεκε Ζεφύρω ἀνέμω Ἅρπυια Ποδάργη

Βοσκομένη λειμῶνι παρὰ ῥόον Ὠκεανοῖο.

Iliad, xvi. 148–51.

Origin of Animal-worship

We now come to consider the special worship of certain animals. The origin of this form of belief may possibly be traced to many different sources.

In the first place, no savage fixes the boundary line between man and the lower forms of animal life so definitely as more civilized races are wont to do. The animal, in their belief, has very much the same soul, much the same feelings and passion as men have, a theory exemplified in the way the Indian ploughman speaks to his ox, or the shepherd calls his flock.

To him, again, the belief is familiar that the spirits of his ancestors appear in the form of animals, as among the Drâvidian races they come in the shape of a tiger which attacks the surviving relatives, or as a chicken which leaves the mark of its footsteps in the ashes when it re-visits its former home.

So, all these people believe that the witch soul wanders about at night, and for want of a better shape enters into some animal, takes the form of a tiger or a bear, or flies through the air like a bird.

All through folk-lore we find the idea that man has kinship [202]with animals generally accepted. We constantly find the girl wooed by the frog, marrying the pigeon, elephant, eagle, or whale. Every child in the nursery reads of the frog Prince, and no savage sees any particular incongruity in his marriage and transformation. In more than one of the Indian tales the childless wife longs for a child and is delivered of a snake.

The incident of animal metamorphosis is also familiar. Thus, in one of Somadeva’s tales his mistress turns a man into an ox; in another his wife transforms him into a buffalo; in a third the angry hermit turns the king into an elephant.1 Everyone remembers the terrific scene of transformation into various animals which makes up the tale of the second Qalandar in the Arabian Nights.

Animals, too, constantly assume other shapes. In one of the Bengal stories the mouse becomes a cat. In other Indian tales the golden deer becomes the mannikin demon, the white hind becomes the white witch, the hero’s mother becomes a black bitch, the hero himself a parrot, and so on.2 In fact a large part of the incidents of Indian stories turns on various forms of metamorphosis, and every English child knows how the lover of Earl Mar’s daughter took the shape of a dove.

We have again the very common incident in the folk-tales of animals understanding the speech of human beings, and men learning the tongue of birds, and the like. Solomon, according to the Qurân, knew the language of animals; in the tales of Somadeva, the Vaisya Bhâshâjna knows the language of all beasts and birds, a faculty which in Germany is gained by eating a white snake.3

Then there is the large cycle of tales in which the grateful animal warns the hero or heroine of approaching danger, as in the story of Bopuluchi, or brings news, or produces gold. [203]The idea of grateful animals assisting their benefactors runs through the whole range of folk-lore.4

Another series of cognate ideas has been very carefully analyzed by Mr. Campbell. The spirits of the dead haunt two places, the house and the tomb. Those who haunt the house are friendly; those who haunt the tomb are unfriendly. Two classes of animals correspond to these two classes of spirits—an at-home, fearless class, as the snake, the rat, flies and ants and bees, into which the home-haunting or friendly spirits would go; and a wild, unsociable class, such as bats and owls, dogs, jackals, or vultures, into which the unfriendly or tomb-haunting spirits would go.

In the case of some of these tomb-haunting animals, the dog, jackal, and vulture, the feeling towards them as tomb-haunters seems to have given place to the belief that as the spirit lives in the tomb where the body is laid, so, if the body be eaten by an animal, the spirit lives in the animal, as in a living tomb.5

Other animals, again, are invested with particular qualities, fierceness and courage, strength or agility, and eating part of their flesh, or wearing a portion as an amulet, conveys to the possessor the qualities of the animal. A familiar instance of this is the belief in the claws and flesh of the tiger as amulets or charms against disease and the influence of evil spirits.

Many animals, too, are respected for their use to man or as scarers of demons, as the cow; as possessors of wisdom, like the elephant or snake; as semi-human in origin or character, as the ape. But it is, perhaps, dangerous to attempt, as Mr. Campbell has done, to push the classification much farther, because the respect paid to any particular animal is possibly based on varied and diverging lines of belief.

Lastly, as Mr. Frazer has shown, many animals are regarded [204]as representing the Corn spirit, and are either revered or killed in their divine forms to promote the return of vegetation with each recurring spring.

Horse-worship

To illustrate some of these principles from the worship of certain special animals, we may begin with the horse.

War horses were so highly prized by the early Aryans in their battles with the aborigines, that the horse, under the name of Dadhikra, “he that scatters the hoar frost like milk,” soon became an object of worship, and in the Veda we have a spirited account of the worship paid to this godlike being.6

Another horse often spoken of in the early legends is Syâma Karna, “he with the black ears,” which alone was considered a suitable victim in the horse sacrifice or Asvamedha. One hundred horse sacrifices entitled the sacrificer to displace Indra from heaven, so the deity was always trying to capture the horse which was allowed to roam about before immolation. The saint Gâlava, who was a pupil of Visvamitra, when he had completed his studies, asked his tutor what fee he should pay.

The saint told him that he charged no fee, but he insisted in asking, till at last the angry Rishi said that he would be content with nothing less than a thousand black-eared horses. After long search Gâlava found three childless Râjas, who had each two hundred such horses, and they consented to exchange them for sons.

Gâlava then went to Yayâti, whose daughter could bear a son for any one and still remain a virgin. By her means the three Râjas became fathers of sons, Visvamitra took them, and to make up the number, had himself two sons by the same mystic bride.

In the Mahâbhârata, Uchchaihsravas, “he with the long ears,” or “he that neighs loudly,” is the king of the horses, and belongs to Indra. He is swift as thought, follows the [205]path of the sun, and is luminous and white, with a black tail, made so by the magic of the serpents, who have covered it with black hair. In the folk-tales he consorts with mares of mortal birth, and begets steeds of unrivalled speed, like the divine Homeric coursers of Æneas.7 In the tales of Somadeva we find the king addressing his faithful horse, and praying for his aid in danger, as Achilles speaks to his steeds Xanthos and Balios, and in the Karling legend of Bayard.8 We meet also with the horse of Manidatta, which was “white as the moon; the sound of its neighing was as musical as that of a clear conch or other sweet-sounding instrument; it looked like the waves of the sea of milk surging on high; it was marked with curls on the neck, and adorned with the crest jewels, the bracelet, and other signs, which it seemed it had acquired by being born in the race of Gandharvas.”

At a later mythological stage we meet Kalki, the white horse which is to be the last Avatâra of Vishnu, and reminds us of the white horse of the Book of Revelation. We meet in the Rig Veda with Yatudhanas, the demon horse, which feeds now upon human flesh (like the Bucephalus of the legend of Alexander), now upon horseflesh, and now upon milk from cows. He has a host of brethren, such as Arvan, half horse, half bird, on which the Daityas are supposed to ride.

Dadhyanch or Dadhîcha has a curious legend. He was a Rishiand. Indra, after teaching him the sciences, threatened to cut his head off if he communicated the knowledge to any one else. But the Aswins tempted him to disobey the god, and then, to save him from the wrath of Indra, cut off his head and replaced it with that of a horse.

Finally Indra found his horse-head in the lake at Kurukshetra, and using it as Sampson did the jaw-bone of the ass, he slew the Asuras. We have, again, Vishnu in the form of Hayagrîva, or “horse-necked,” which he assumed to save [206]the Veda, carried off by two Asuras, and in another shape he is Hayasiras or Hayasîrsha, which vomits forth fire and drinks up the waters.

In the Purânas we meet the Daitya Kesi, who assumes the form of a horse and attacks Krishna, but the hero thrusts his hand into his mouth and rends him asunder. A large chapter of Scottish folk-lore depends on the doings of magic horses such as these.9

The flying horse of the Arabian Nights has been transferred into many of the current folk-tales, and has found its way into European folk-lore.10 In the same connection we meet the magic bridle; the flying car, such as Pushpaka, the flying vehicle of Kuvera, the god of wealth; the flying bed, the Urân Khatola of the Indian tales; the flying boat, and the flying shoes.11

There are numerous other horses famous in Hindu legend. The saint Alam Sayyid of Baroda was known as Ghorê Kâ Pîr, or the horse saint. His horse was buried near him, and Hindus hang images of the animal on trees round his tomb.12 We have already spoken of Gûga and his mare Javâdiyâ. The horse of the king of Bhilsa or Bhadrâvatî was of dazzling brightness, and regarded as the palladium of the kingdom, but in spite of all the care bestowed upon it, it was carried off by the Pândavas.

There is a stock horse miracle story told in connection with Lâl Beg, the patron saint of the sweepers. The king of Delhi lost a valuable horse, and the sweepers were ordered to bury it, but as the animal was very fat, they proceeded to cut it up for themselves, giving one leg to the king’s priest.

They took the meat home and proceeded to cook it, but being short of salt, they sent an old woman to buy some. She went to the salt merchant’s shop and pressed him to serve her at once, “If you do not hurry,” said she, “a thousand rupees’ worth of meat will be ruined.” He informed the king, who, suspecting the state of the case, ordered the [207]sweepers to produce the horse.

They were in dismay at the order, but they laid what was left of the animal on a mound sacred to Lâl Beg, and prayed to him to save them, whereupon the horse stood up, but only on three legs. So they went to the king and confessed how they had disposed of the fourth leg. The unlucky priest was executed, and the horse soon after died also.13

The horse is regarded as a lucky and exceedingly pure animal. When a cooking vessel has become in any way defiled, a common way of purifying it is to make a horse smell it. In the Dakkhin it is said that evil spirits will not approach a horse for fear of his foam.14 In Northern India, the entry of a man on horseback into a sugar-cane field during sowing time is regarded as auspicious.

This taking of omens from horses was well known in Germany, and Tacitus says, “Proprium gentis equorum praesagia ac monitus experiri, hinnitus ac fremitus observant.”15 There does not appear to be in India any trace of the idea prevalent in England that the horse has the power of seeing ghosts, or that it can cure diseases such as whooping cough.16 But, like the bull, the stallion is believed to scare the demon of barrenness.

In the Râmâyana, Kausalyâ touches the stallion in the hope of obtaining sons, and with the same object the king and queen smell the odour of the burnt marrow or fat of the horse. The water in which a fish is washed has the same effect on women in Western folk-lore. With the same object, at the Asvamedha, the queen lies at night beside the slain sacrificial horse.17

It is popularly supposed that the horse originally had wings, and that the chestnuts or scars on the legs are the places where the wings originally grew. Eating horseflesh is supposed to bring on cramp, and when a Sepoy at rifle practice misses the target, his comrades taunt him with having eaten the unlucky meat.18 [208]

Modern Horse-worship

Of modern horse-worship there are many examples. The Palliwâl Brâhmans of Jaysalmer worship the bridle of a horse, which Colonel Tod supposes to prove the Scythic origin of the early colonists, who were equestrian as well as nomadic.19 Horse-worship is still mixed up with the creed of the Buddhists of Yunân, who doubtless derived it from India.20

In Western India this form of worship is common. It is the chief object of reverence at the Dasahra festival. Some Râjput Bhîls worship a deity called Ghorâdeva or a stone horse; the Bhâtiyas worship a clay horse at the Dasahra, and the Ojha Kumhârs erect a clay horse on the sixth day after birth, and make the child worship it. Rag horses are offered at the tombs of saints at Gujarât.

The Kunbis wash their horses on the day of the Dasahra, decorate them with flowers, sacrifice a sheep to them, and sprinkle the blood on them.21 The custom among the Drâvidian races of offering clay horses to the local gods has been already noticed. The Gonds have a horse godling in Kodapen, and at the opening of the rainy season they worship a stone in his honour outside the village.

A Gond priest offers a pottery image of the animal and a heifer, saying, “Thou art our guardian! Protect our oxen and cows! Let us live in safety!”22 The heifer is then sacrificed and the meat eaten by the worshippers. The Devak or marriage guardian of some of the Dakkhin tribes is a horse.

The Worship of the Ass

The contempt for the ass seems to have arisen in post-Vedic times. Indra had a swift-footed ass, and one of the epithets of Vikramaditya was Gadharbha-rûpa, or “he in the form of an ass.” The Vishnu Purâna tells of the demon Dhenuka, who took the form of an ass and began to kick Balarâma and Krishna, as they were plucking fruit in the demon’s grove. Balarâma seized him, with sundry of his [209]companions and flung him on the top of a palm tree. Khara, a cannibal Râkshasa who was killed by Râma Chandra, also used to take the form of an ass. Muhammad said, “The most ungrateful of all voices is surely the voice of asses.” Muhammadans believe that the last animal which entered the ark was the ass to which Iblîs was clinging.

At the threshold the beast seemed troubled and could enter no farther, when Noah said unto him, “Fie upon thee! Come in!” But as the ass was still in trouble and did not advance, Noah cried, “Come in, though the Devil be with thee!” So the ass entered, and with him Iblîs. Thereupon Noah asked, “O enemy of Allah! Who brought thee into the ark?” And Iblîs answered, “Thou art the man, for thou saidest to the ass, ‘Come in, though the Devil be with thee!’”23

The worship of the ass is chiefly associated with that of Sîtalâ, whose vehicle he is. The Agarwâla sub-caste of Banyas have a curious rule of making the bridegroom just before marriage mount an ass. This is done in secret, and though said to be intended to propitiate the goddess of small-pox, is possibly a survival of some primitive form of worship.

In folk-lore the ass constantly appears. We have in Somadeva the fable of the ass in the panther’s skin, which also appears in the fifth book of the Panchatantra. Professor Weber asserts that it was derived from the original in Æsop, but this is improbable, as it is also found in the Buddhist Jâtakas.

In one of the Kashmîr tales we have the bird saying, “If any person will peel off the bark of my tree, pound it, mix the powder with some of the juice of its leaves and then work it into a ball, it will be found to work like a charm; for any one who smells it will be turned into an ass.”24 We have instances of ass transformation in Apuleius and Lucian, and in German and other Western folk-tales. [210]

The Lion

The lion, from his comparative rarity in Northern India, appears little in popular belief. It is one of the vehicles of Pârvatî, and rude images of the animal are sometimes placed near shrines dedicated to Devî. There is a current idea that only one pair of lions exists in the world at the same time.

They have two cubs, a male and a female, which, when they arrive at maturity, devour their parents. In the folk-tales the childless king is instructed that he will find in the forest a boy riding on a lion, and this will be his son. The lovely maiden in the legend of Jimutavâhana is met riding on a lion.

We have the lion Pingalika, king of beasts, with the jackal as his minister, and in one of the cycle of tales in which the weak animal overcomes the more powerful, the hare by his wisdom causes the lion to drown himself. The basis of the famous tale of Androcles is probably Buddhistic, but only a faint reference to it is found in Somadeva. In one of the modern stories the soldier takes a thorn out of the tiger’s foot, and is rewarded with a box which contains a manikin, who procures for him all he desires.25

The Tiger

The tiger naturally takes the place of the lion. According to the comparative mythologists, “the tiger, panther, and leopard possess several of the mystical characteristics of the lion as the hidden sun. Thus, Dionysos and Siva, the phallical god par excellence, have these animals as their emblems.”26 Siva, it is true, is represented as sitting in his ascetic form on a tiger skin, but it is his consort, Durgâ, who uses the animal as her vehicle.

Quite apart from the solar myth theory, the belief that witches are changed into tigers, and the terror inspired by him, are quite sufficient to account for the honour bestowed upon him. [211]

Much also of the worship of the tiger is probably of totemistic origin. Thus the Baghel Râjputs claim descent, and from him (bâgh, vyâghra, “the spotted one”) derive their name. This tribe will not, in Central India, destroy the animal. So, “no consideration will induce a Sumatran to catch or wound a tiger, except in self-defence, or immediately after the tiger has destroyed a friend or a relation.

When a European has set traps for tigers, the people of the neighbourhood have been known to go by night to the spot and explain to the tiger that the traps were not set by them, nor with their consent.” The Bhîls and the Bajrâwat Râjputs of Râjputâna also claim tiger origin.27

Another idea appearing in tiger-worship is that he eats human flesh, and thus obtains possession of the souls of the victims whom he devours. For this reason a man-eating tiger is supposed to walk along with his head bent, because the ghosts of his victims sit on it and weigh it down.28

He is, again, often the disguise of a sorcerer of evil temper, an idea similar to that which was the basis of the European dread of lycanthropy and the were-wolf. “Accounts differ as to the way in which the were-wolf was chosen. According to one account, a human victim was sacrificed, one of his bowels was mixed with the bowels of animal victims, the whole was consumed by the worshippers, and the man who unwittingly ate the human bowel was changed into a wolf.

According to another account, lots were cast among the members of a particular family, and he upon whom the lot fell was the were-wolf. Being led to the brink of a tarn, he stripped himself, hung his clothes on an oak tree, plunged into the tarn, and swimming across it, went into desert places.

There he was changed into a wolf, and herded with wolves for nine years. If he tasted human blood before the nine years were out he had to remain a wolf for ever. If during the nine years he [212]abstained from preying on men, then, when the tenth year came round, he recovered his human shape. Similarly, there is a negro family at the mouth of the Congo who are supposed to possess the power of turning themselves into leopards in the gloomy depths of the forest. As leopards, they knock people down, but do no further harm, for they think that if, as leopards, they once lapped blood, they would be leopards for ever.”29

Hence in India the jungle people who are in the way of meeting him will not pronounce his name, but speak of him as Gîdar, “the jackal,” Jânwar, “the beast,” or use some other euphemistic term. They do the same in many cases with the wolf and bear, and though they sometimes hesitate to kill the animal themselves, they will readily assist sportsmen to destroy him, and make great rejoicings when he is killed.

A Shikâri will break off a branch on the road as he goes along, and say, “As thy life has departed, so may the tiger die!” When he is killed they will bring forward some spirits and pour it on the head of the animal, addressing him, “Mahârâja! During your life you confined yourself to cattle, and never injured your human subjects.

Now that you are dead, spare us and bless us!” In Akola the gardeners are unwilling to inform the sportsmen of the whereabouts of a tiger or panther which may have taken up its quarters in their plantation, for they have a superstition that a garden plot loses its fertility from the moment one of these animals is killed there. So, with the Ainos of Japan, who when a bear is trapped or wounded by an arrow, go through an apologetic or propitiatory ceremony.30

In Nepâl they have a regular festival in honour of the tiger known as the Bâgh Jâtra, in which the worshippers used to dance in the disguise of tigers. [213]

worship among the Jungle Races

But, as is natural, the worship of the tiger prevails more widely among the jungle races. We have already met with Bâgheswar, the tiger deity of the Mirzapur forest tribes. The Santâls also worship him, and the Kisâns honour him as Banrâja, or “lord of the jungle.” They will not kill him, and believe that in return for their devotion he will spare them. Another branch of the tribe does not worship him, but all swear by him. The Bhuiyârs, on the contrary, have no veneration for him, and think it their interest to slay him whenever they have an opportunity.

The Juângs take their oaths on earth from an ant-hill, and on a tiger’s skin; the ant-hill is a sacred object with the Khariyas, and the tiger skin is brought in when the Hos and Santâls are sworn. Among the eastern Santâls, the tiger is worshipped, but in Râmgarh only those who have suffered from the animal’s ferocity condescend to adore him. If a man is carried off by a tiger, the Bâgh Bhût, or “Tiger ghost,” is worshipped, and an oath on a tiger’s skin is considered most solemn.31

Bâgh Deo, the Tiger Godling

Further west the Kurkus of Hoshangâbâd worship the tiger godling, Bâgh Deo, who is the Wâgh Deo of Berâr. At Petri in Berâr is a sort of altar to Wâghâî Devî, the tiger goddess, founded on a spot where a Gond woman was once seized by a tiger. She is said to have vanished as if by some supernatural agency, and the Gonds who desire protection from wild beasts present to her altar gifts of every kind of animal from a cow downwards. A Gond presides over the shrine and receives the votive offerings.

In Hoshangâbâd the Bhomka is the priest of Bâgh Deo. “On him devolves the dangerous duty of keeping tigers out of the boundaries. When a tiger visits a village, the Bhomka repairs to Bâgh Deo, and makes his offerings to the god, and promises to repeat them for so many years on condition [214]that the tiger does not appear for that time. The tiger, on his part, never fails to fulfil the compact thus solemnly made by his lord; for he is pre-eminently an upright and honourable beast—‘pious withal,’ as Mandeville says, not faithless or treacherous like the leopard, whom no compact can bind.

Some Bhomkas, however, masters of more powerful spell, are not obliged to rely on the traditional honour of the tiger, but compel his attendance before Bâgh Deo; and such a Bhomka has been seen, a very Daniel among tigers, muttering his incantations over two or three at a time as they crouched before him. Still more mysterious was the power of Kâlibhît Bhomka (now, alas! no more).

He died, the victim of misplaced confidence in a Louis Napoleon of tigers, the basest and most bloodthirsty of his race. He had a fine large Sâj tree into which, when he uttered his spells, he would drive a nail. On this the tiger came and ratified the contract with enormous paw manual. Such was that of Timûr the Lame, when he dipped his mighty hand in blood and stamped its impression on a parchment grant.”32

In the same way in other parts of the Central Provinces the village sorcerers profess to be able to call tigers from the jungles, to seize them by the ears, and control their voracity by whispering to them a command not to come near their villages, or they pretend to know a particular kind of root, by burying which they can prevent the beasts of the forest from devouring men or cattle. With the same object they lay on the pathway small models of bedsteads and other things which are supposed to act as charms and stop their advance.

Magical Powers of Dead Tigers

All sorts of magical powers are ascribed to the tiger after death. The fangs, the claws, the whiskers are potent charms, valuable for love philters and prophylactics against demoniacal influence, the Evil Eye, disease and death. The [215]milk of a tigress is valuable medicine, and it is one of the stock impossible tasks or tests imposed upon the hero to find and fetch it, as he is sent to get the feathers of the eagle, water from the well of death, or the mystical cow guarded by Dânos or Râkshasas.33 The fat is considered a valuable remedy for rheumatism and similar maladies.

The heart and flesh are tonics, stimulants and aphrodisiacs, and give strength and courage to those who use them. The Miris of Assam prize tiger’s flesh as food for men; it gives them strength and courage; but it is not suited for women, as it would make them too strong-minded.34 The whiskers are believed, among other qualities which they possess, to be a slow poison when taken with food, and the curious rudimentary clavicles, known as Santokh or “happiness,” are highly valued as amulets. There is a general belief that a tiger gets a new lobe to his liver every year.

A favourite amulet to repel demoniacal influence consists of the whiskers of the tiger or leopard mixed with nail parings, some sacred root or grass, and red lead, and hung on the throat or upper arm. This treatment is particularly valuable in the case of young children immediately after birth.

Tiger’s flesh is also a potent medicine and charm, and it is burnt in the cow-stall when cattle disease prevails. The flesh of the tiger, or if that be not procurable, the flesh of the jackal is burnt in the fields to keep off blight from the crops.

Tigers, Propitiation of

Some tigers are supposed to be amenable to courtesy. In one of the Kashmîr tales, the hero in search of tiger’s milk shoots an arrow and pierces one of the teats of the tigress, to whom he explains that he hoped she would thus be able to suckle her cubs with less trouble. In other tales we find the tiger pacified if he is addressed as “Uncle.”35 So, Colonel Tod describes how a tiger attacked a boy near his camp, and was supposed to have, like the fierce Râkshasa of the Nepâl [216]legend, released the child when he was addressed as “Uncle.”36 “This Lord of the Black Rock, for such is the designation of the tiger, is one of the most ancient bourgeois of Morwan; his stronghold is Kâla Pahâr, between this and Magawâr; and his reign during a long series of years has been unmolested, notwithstanding numerous acts of aggression on his bovine subjects.

Indeed, only two nights before he was disturbed gorging on a buffalo belonging to a poor oilman of Morwan. Whether the tiger was an incarnation of one of the Mori lords of Morwan, tradition does not say; but neither gun, bow, nor spear has ever been raised against him. In return for this forbearance, it is said, he never preyed on man; or if he seized one, would, on being entreated with the endearing epithet of ‘Uncle,’ let go his hold.”37

Tiger-worship among the Gonds

Among the Gonds tiger-worship assumes a particularly disgusting form. At marriages among them, a terrible apparition appears of two demoniacs possessed by Bâgheswar, the tiger god. They fall ravenously on a bleating kid, and gnaw it with their teeth till it expires. “The manner,” says Captain Samuells, who witnessed the performance, “in which the two men seized the kid with their teeth and killed it was a sight which could only be equalled on a feeding day in the Zoological Gardens or a menagerie.”38

Men Metamorphosed into Tigers

The only visible difference between the ordinary animal and a man metamorphosed into a tiger was explained to Colonel Sleeman to consist in the fact that the latter had no tail. In the jungles about Deori there is said to be a root, which if a man eats, he is converted into a tiger on the spot; and if, when in this state, he eats another species of root, he is turned back into a man again. [217]

“A melancholy instance of this,” said Colonel Sleeman’s informant, “occurred in my own father’s family when I was an infant. His washerman Raghu was, like all washermen, a great drunkard. Being seized with a violent desire to ascertain what a man felt like in the state of a tiger, he went one day to the jungle and brought back two of these roots, and desired his wife to stand by with one of them, and the instant she saw him assume the tiger’s shape to thrust the root she held into his mouth.

She consented, and the washerman ate his root and instantly became a tiger, whereupon she was so terrified that she ran off with the antidote in her hand. Poor old Raghu took to the woods, and there ate a good many of his friends from the neighbouring villages; but he was at last shot, and recognized from his having no tail. You may be quite sure when you hear of a tiger having no tail that it is some unfortunate man who has eaten of that root, and of all the tigers he will be found the most mischievous.”39

This is a curious reversal of the ordinary theory regarding the tail of the tiger, to which a murderous strength is attributed. A Hindu proverb says that the hair of a tiger’s tail may be the means of losing one’s life. This has been compared by Professor De Gubernatis with the tiger Mantikora spoken of by Ktesias, which has on its tail hairs which are darts thrown by it for the purpose of defence.40

A Nepâl legend describes how some children made a clay image of a tiger, and thinking the figure incomplete without a tongue, went to fetch a leaf to supply the defect. On their return they found that Bhairava had entered the image and had begun to devour their sheep. The image of Bâgh Bhairava and the deified children are still to be seen at this place. We have the same legend in the Panchatantra and the tales of Somadeva, where four Brâhmans resuscitate a tiger and are devoured by it.41

We have many instances in the folk-tales of the tiger befooled. [218]In one of the tales told by the Mânjhis of Mirzapur the goat has kids in the tiger’s den, and when he arrives she makes her kids squall and pretends that she wants some tiger’s flesh for them.42 In a Panjâbi tale the farmer’s wife rides up to the tiger calling out, “I hope I may find a tiger in this field, for I have not tasted tiger’s flesh since the day before yesterday, when I killed three,” whereupon the tiger runs away. The tale which tells how the jackal succeeds in getting the tiger back into the cage and thus saves the Brâhman is common in Indian folk-lore.43

Dog-worship

In the Nepâl legend which we have been discussing we find Bhairava associated with the tiger, but his prototype, the local godling Bhairon, has the dog as his sacred animal, and his is the only temple in Benares into which the dog is admitted.44

Two conflicting lines of thought seem to meet in dog-worship. As Mr. Campbell says, “There is a good house-guarding dog, and an evil scavenging and tomb-haunting dog. Some of the products of the dog are so valued in driving off spirits that they seem to be a distinct element in the feeling of respect shown to the dog.

Still it seems better to consider the dog as a man-eater, and to hold that, like the tiger, this was the original reason why the dog was considered a guardian.”45 It is perhaps in this connection that the dog is associated with Yama, the god of death.

An ancient epithet of the dog is Kritajna, “he that is mindful of favours,” which is also a title of Siva. The most touching episode of the Mahâbhârata is where Yudhisthira refuses to enter the heaven of Indra without his favourite dog, which is really Yama in disguise. These dogs of Yama probably correspond to the Orthros and Kerberos of the Greeks, and Kerberos has been connected etymologically [219]with Sarvari, which is an epithet of the night, meaning originally “dark” or “pale.”46 The same idea shows itself in the Pârsi respect for the dog, which may be traced to the belief of the early Persians.

The dog’s muzzle is placed near the mouth of the dying Pârsi in order that it may receive his parting breath and bear it to the waiting angel, and the destruction of a corpse by dogs is looked on with no feeling of abhorrence.

The same idea is found in Buddhism, where on the early coins “the figure of a dog in connection with a Buddhist Stûpa recalls to mind the use to which the animal was put in the bleak highlands of Asia in the preferential form of sepulchre over exposure to birds and wild beasts in the case of deceased monks or persons of position in Tibet. Strange and horrible as it may seem to us to be devoured by domestic dogs, trained and bred for the purpose, it was the most honourable form of burial among Tibetans.”47

The Kois of Central India hold in great respect the Pândava brethren Arjuna and Bhîma. The wild dogs or Dhol are regarded as the Dûtas or messengers of the heroes, and the long black beetles which appear in large numbers at the beginning of the hot weather are called the Pândavas’ goats. None of them will on any account interfere with these divine dogs, even when they attack their cattle.48

Dog-worship: Bhairon

In modern times dog-worship appears specially in connection with the cultus of Bhairon, the Brâhmanical Bhairava, the Bhairoba of Western India. No Marâtha will lift his hand against a dog, and in Bombay many Hindus worship the dog of Kâla Bhairava, though the animal is considered unclean by them. Khandê Râo or Khandoba or Khandoji is regarded as an incarnation of Siva and much [220]worshipped by Marâthas.

He is most frequently represented as riding on horseback and attended by a dog and accompanied by his wife Malsurâ, another form of Pârvatî. His name is usually derived from the Khanda or sword which he carries, but Professor Oppert without much probability would connect it with that of the aboriginal Khândhs who are supposed to have been original settlers in Khândesh, after whom it was called.49 In many temples of Bhaironnâth, as at Benares and Hardwâr, he is depicted on the wall in a deep blue colour approaching to black, and behind him is the figure of the dog on which he rides. Sweetmeat sellers make little images of a dog in sugar, which are presented to the deity as an offering.

At Lohâru, in the Panjâb, a common-looking grave is much respected by the Hindus. It is said to contain the remains of a dog formerly possessed by the chief of the victorious Thâkurs, which is credited with having done noble service in battle, springing up and seizing the wounded warriors’ throats, many of whom it slew. Finally it was killed and buried on the spot with beat of drum, and has since been an object of worship and homage. “Were it not,” says General Cunningham, “for the Sagparast of Naishapur, mentioned in Khusru’s charming Darvesh tales, this example of dog-worship would probably be unique.”50 This is, it is hardly necessary to say, a mistake.

Thus, close to Bulandshahr, there is a grove with four tombs, which are said to be the resting-place of three holy men and their favourite dog, which died when the last of the saints departed this life. They were buried together, and their tombs are held in much respect by Muhammadans.51

In Pûna, Dattâtreya is guarded by four dogs which are said to stand for the four Vedas, and at Jejuri and Nâgpur children are dedicated to the dogs of Khandê Râo. The Ghisâdis, on the seventh day after a birth, go and worship water, and on coming back rub their feet on a dog. At [221]Dharwâr, on the fair day of the Dasahra at Malahâri’s temple, the Vâggayya ministrants dress in blue woollen coats and meet with bell and skins tied round their middles, the pilgrims barking and howling like dogs. Each Vâggayya has a wooden bowl into which the pilgrims put milk and plantains.

Then the Vâggayyas lay down the bowls, fight with each other like dogs, and putting their mouths into the bowls, eat the contents.52 In Nepâl, there is a festival, known as the Khichâ Pûjâ, in which worship is done to dogs, and garlands of flowers are placed round the neck of every dog in the country.53 Among the Gonds, if a dog dies or is born, the family has to undergo purification.54

Dogs in Folk-lore: The Bethgelert Legend

The famous tale of Bethgelert, the faithful hound which saves the child of his master from the wolf and is killed by mistake, appears all through the folk-tales and was probably derived from India. In the Indian version the dog usually belongs to a Banya or to a Banjâra, who mortgages him to a merchant.

The merchant is robbed and the dog discovers the stolen goods. In his gratitude the merchant ties round the neck of the dog a scrap of paper, on which he records that the debt has been satisfied. The dog returns to his original master, who upbraids him for deserting his post, and, without looking at the paper, kills him, only to be overcome by remorse when he learns the honesty of the faithful beast.

This famous tale is told at Haidarâbâd, Lucknow, Sîtapur, Mirzapur, and Kashmîr. In its more usual form, as in the Panchatantra and the collection of Somadeva, the mungoose takes the place of the dog and kills the cobra on the baby’s cradle.55

Throughout folk-lore the dog is associated with the [222]spirits of the dead, as we have seen to be the case with Syâma, “the black one,” and Sabala or Karvara, the “spotted ones,” the attendants of Yama.56 Hence the dog is regarded as the guardian of the household, which they protect from evil spirits.

According to Aubrey,57 “all over England a spayed bitch is accounted wholesome in a house; that is to say they have a strong belief that it keeps away evil spirits from haunting of a house.” As in the Odyssey, the two swift hounds of Telemachus bear him company and recognize Athene when she is invisible to others, and the dogs of Virgil howl when the goddess approaches, so the Muhammadans believe that dogs recognize Azraîl, the angel of death, and in Northern India it is supposed that dogs have the power of seeing spirits, and when they see one they howl. In Shakespeare King Henry says:—

“The owl shriek’d at thy birth, an evil sign;

The night-crow cried, aboding luckless time;

Dogs howled and hideous tempests shook down trees.”

Hence in all countries the howling of dogs in the vicinity of a house is an omen of approaching misfortune.

The respect for the dog is well shown in the case of the Bauris of Bengal, who will on no account kill a dog or touch its body, and the water of a tank in which a dog has been drowned cannot be used until an entire rainy season has washed the impurity away. They allege that as they kill cows and most other animals, they deem it right to fix on some beast which should be as sacred to them as the cow to the Brâhman, and they selected the dog because it was a useful animal when alive and not very nice to eat when dead, “a neat reconciliation of the twinges of conscience and cravings of appetite.”58

Various omens are in the Panjâb drawn from dogs. When out hunting, if they lie on their backs and roll, as they generally do when they find a tuft of grass or soft ground, it shows that plenty of game will be found. If a [223]dog lies quietly on his back in the house, it is a bad omen, for the superstition runs that the dog is addressing heaven for support, and that some calamity is bound to happen.59

We have seen already that some of the Central Indian tribes respect the wild dog. The same is the case in the Hills, where they are known as “God’s hounds,” and no native sportsman will kill them.60 In one of Grimm’s tales we read that the “Lord God had created all animals, and had chosen out the wolf to be his dog,” and the dogs of Odin were wolves.61 Another sacred dog in Indian folk-lore is that of the hunter Shambuka. His master threw him into the sacred pool of Uradh in the Himâlaya.

Coming out dripping, he shook some of the water on his owner, and such was the virtue of even this partial ablution that on their death both hunter and dog were summoned to the heaven of Siva.62

All over Northern India the belief in the curative power of the tongue of the dog widely prevails. In Ireland they say that a dried tongue of a fox will draw out thorns, however deep they be, and an old late Latin verse says:—

In cane bis bina sunt, et lingua medicina

Naris odoratus, amor intiger, atque latratus.63

Among Musalmâns the dog is impure. The vessel it drinks from must be washed seven times and scrubbed with earth. The Qurân directs that before a dog is slipped in chase of game, the sportsman should call out, “In the name of God, the great God!” Then all game seized by him becomes lawful food.

The Goat

The goat is another animal to which mystic powers are attributed. In the mythology of the West he is associated with Dionysos, Pan, and the Satyr. In England it is commonly [224]believed that he is never seen for twenty-four hours together, and that once in this space he pays a visit to the Devil to have his beard combed.64 The Devil, they say, sometimes appears in this form, which accounts for his horns and tail. The wild goat was associated with the worship of Artemis, the Arab unmarried goddess.65 In the Râmâyana, Agamukhî, or “goat’s face,” is the witch who wishes Sîtâ to be torn to pieces.

Mr. Conway asks whether this idea about the goat is due to the smell of the animal, its butting and injury to plants, or was it demonized merely because of its uncanny and shaggy appearance?66 Probably the chief reason is because it has a curious habit of occasionally shivering, which is regarded as caused by some indwelling spirit. The Thags in their sacrifice used to select two goats, black, and perfect in all their parts.

They were bathed and made to face the west, and if they shook themselves and threw the water off their hair, they were regarded as a sacrifice acceptable to Devî. Hence in India a goat is led along a disputed boundary, and the place where it shivers is regarded as the proper line. Plutarch says that the Greeks would not sacrifice a goat if it did not shiver when water was thrown over it.

In the Panjâb it is believed that when a goat kills a snake it eats it and then ruminates, after which it spits out a Manka or bead, which, when applied to a snake-bite, absorbs the poison and swells. If it be then put in milk and squeezed, the poison drips out of it like blood, and the patient is cured. If it is not put in milk, it will burst to pieces.67 It hence resembles the Ovum Anguinum, or Druid’s Egg, to which reference has been already made.68 If a person suffers from spleen, they take the spleen of a he-goat, if the patient be a male; or of a she-goat, if the patient be a female.

It is rubbed on the region of the spleen seven times on a Sunday or Tuesday, pierced with acacia thorns and hung on a [225]tree. As the goat’s spleen dries, the spleen of the patient reduces.

The horn is regarded as somehow most closely connected with the brain. So, in the “Merry Wives of Windsor,” Mrs. Quickly says: “If he had found the young man, he would have been horn mad,” and Horace gives the advice, “Fenum habet in cornu longe fuge.” Martial describes how in his time the Roman shrines were covered with horns, Dissimulatque deum cornibus ora frequens.69

It is for this reason that the local shrines in the Himâlaya are decorated with horns of the wild sheep, ibex, and goat. In Persia many houses are adorned with rams’ heads fixed to the corners near the roof, which are to protect the building from misfortune. In Bilochistân and Afghanistân it is customary to place the horns of the wild goat and sheep on the walls of forts and mosques.70 Akbar covered his Kos Minars or mile-stones with the horns of the deer he had killed. The conical support of the Banjâra woman’s head-dress was originally a horn, and many classes of Faqîrs tie a piece of horn round their necks. We have the well-known horn of plenty, and it is very common in the folk-tales to find objects taken out of the ears or horns of the helpful animals.71

Goat and Totemism

We perhaps get a glimpse of totemism in connection with the goat in some of the early Hindu legends. When Parusha, the primeval man, was divided into his male and female parts, he produced all the animals, and the goat was first formed out of his mouth. There is, again, a mystical connection between Agni, the fire god, Brâhmans, and goats, as between Indra, the Kshatriyas, and sheep, Vaisyas and kine, Sûdras and the horse. These may possibly have been tribal [226]totems of the races by whom these animals were venerated.72 The sheep, as we have already seen, is a totem of the Keriyas.

The Aheriyas, a vagrant tribe of the North-Western Provinces, worship Mekhasura or Meshasura in the form of a ram.

Cow and Bull Worship

But the most famous of these animal totems or fetishes is the cow or bull. According to the school of comparative mythology the bull which bore away Europe from Kadmos is the same from which the dawn flies in the Vedic hymn.

He, according to this theory, is “the bull Indra, which, like the sun, traverses the heaven, bearing the dawn from east to west. But the Cretan bull, like his fellow in the Gnossian labyrinth, who devours the tribute children from the city of the Dawn goddess, is a dark and malignant monster, akin to the throttling snake who represents the powers of night and darkness.”73 This may be so, but the identification of primitive religion, in all its varied phases, with the sun or other physical phenomena is open to the obvious objection that it limits the ideas of the early Aryans to the weather and their dairies, and antedates the regard for the cow to a period when the animal was held in much less reverence than it is at present.

Respect for the Cow Modern

That the respect for the cow is of comparatively modern date is best established on the authority of a writer, himself a Hindu. “Animal food was in use in the Epic period, and the cow and bull were often laid under requisition. In the Aitareya Brâhmana, we learn that an ox, or a cow which suffers miscarriage, is killed when a king or honoured guest is received. In the Brâhmana of the Black Yajur Veda the kind and character of the cattle which should be slaughtered in minor sacrifices for the gratification of particular divinities [227]are laid down in detail.

Thus a dwarf one is to be sacrificed to Vishnu, a drooping-horned bull to Indra, a thick-legged cow to Vâyu, a barren cow to Vishnu and Varuna, a black cow to Pûshan, a cow having two colours to Mitra and Varuna, a red cow to Indra, and so on. In a larger and more important ceremonial, like the Aswamedha, no less than one hundred and eighty domestic animals, including horses, bulls, goats, sheep, deer, etc., were sacrificed.

“The same Brâhmana lays down instructions for carving, and the Gopatha Brâhmana tells us who received the portions. The priests got the tongue, the neck, the shoulder, the rump, the legs, etc., while the master of the house wisely appropriated to himself the sirloin, and his wife had to be satisfied with the pelvis. Plentiful libations of Soma beer were to be allowed to wash down the meat. In the Satapatha Brâhmana we have a detailed account of the slaughter of a barren cow and its cooking.

In the same Brâhmana there is an amusing discussion as to the propriety of eating the meat of an ox or cow. The conclusion is not very definite. ‘Let him (the priest) not eat the flesh of the cow and the ox.’ Nevertheless Yajnavalkya said (taking apparently a very practical view of the matter), ‘I, for one, eat it, provided it is tender.’”74

The evidence that cows were freely slaughtered in ancient times could be largely extended. It is laid down in the early laws that the meat of milch cows and oxen may be eaten, and a guest is called a Goghna or “cow-killer,” because a cow was killed for his entertainment.75 In the Grihya Sûtra we have a description of the sacrifice of an ox to Kshetrapati, “the lord of the fields.” In another ancient ritual the sacrifice of a cow is stated to be very similar to that of the Satî, and, according to an early legend, kine were created from Parusha, the primal male, and are to be eaten as they were formed from the receptacle of food.76 [228]

It need hardly be said that the worship of the cow is not peculiar to India, but prevails widely in various parts of the world.77

Origin of Cow-worship

The explanation of the origin of cow-worship has been a subject of much controversy. The modern Hindu, if he has formed any distinct ideas at all on the subject, bases his respect for the cow on her value for supplying milk, and for general agricultural purposes.

The Panchagâvya, or five products of the cow—milk, curds, butter, urine, and dung—are efficacious as scarers of demons, are used as remedies in disease, and play a very important part in domestic ritual Gaurochana, a bright yellow pigment prepared from the urine or bile of the cow, or, as is said by some, vomited by her or found in her head, is used for making the sectarial mark, and as a sedative, tonic, and anthelmintic. In Bombay it is specially used as a remedy for measles, which is considered to be a spirit disease.78

There is, again, something to be said for the theory which finds in these animals tribal totems and fetishes.79 We have a parallel case among the Jews, where the bull was probably the ancient symbol of the Hyksos, which the Israelites having succeeded them could adopt, especially as it may have been retained in use by their confederates the Midianites; and it appears in the earliest annals of Israel as a token of the former supremacy of Joseph and his tribe, and was subsequently adopted as an image of Iahveh himself.

So, speaking of Egypt, Mr. Frazer writes: “Osiris was regularly identified with the bull Apis of Memphis and the bull Mnevis of Heliopolis. But it is hard to say whether [229]these bulls were embodiments of him as the corn spirit, as the red oxen appear to have been, or whether they were not entirely distinct deities which got fused with Osiris by syncretism. The fact that these two bulls were worshipped by all the Egyptians, seems to put them on a different footing from the ordinary sacred animals, whose cults were purely local. Hence, if the latter were evolved from totems, as they probably were, some other origin would have to be found for the worship of Apis and Mnevis.

If these bulls were not originally embodiments of the corn god Osiris, they may possibly be descendants of the sacred cattle worshipped by a pastoral people. If this were so, ancient Egypt would exhibit a stratification of the three great types of religion corresponding to the three great stages of society. Totemism or (roughly speaking) the worship of wild animals—the religion of society in the hunting stage—would be represented by the worship of the local sacred animals; the worship of cattle—the religion of society in the pastoral stage—would be represented by the cults of Apis and Mnevis; and the worship of cultivated plants, especially of corn—the religion of society in the agricultural stage—would be represented by the worship of Osiris and Isis. The Egyptian reverence for cows, which were never killed, might belong either to the second or third of these stages.”80

There is some evidence that the same process of religious development may have taken place in India.

It is at least significant that the earlier legends represent Indra as created from a cow; and we know that Indra was the Kuladevatâ or family godling of the race of the Kusikas, as Krishna was probably the clan deity of some powerful confederation of Râjput tribes. Cow-worship is thus closely connected with Indra and with Krishna in his forms as the “herdman god,” Govinda or Gopâla; and it is at least plausible to conjecture that the worship of the cow may have been due to the absorption of the animal as a tribal totem of the two races, who venerated these two divinities.

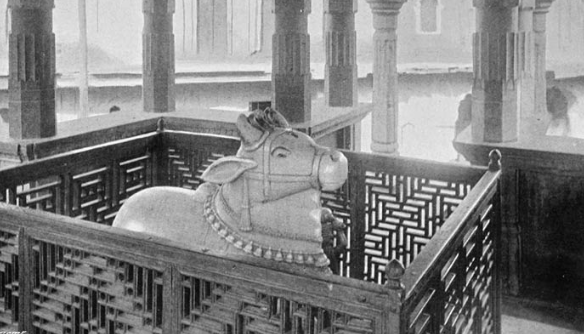

Further, the phallic significance of the worship, in its [230]modern form at least, and its connection with fertility cannot be altogether ignored.81 This is particularly shown in the close connection between Siva’s bull Nandi and the Lingam worship; and there seems reason to suspect that the bull is intended to intercept the evil influences which in the popular belief are continually emitted from the female principle through the Yonî. As we have already seen, the dread of this form of pollution is universal.

Hence when the Lingam is set up in a new village the people are careful in turning the spout of the Yonî towards the jungle, and not in the direction of the roads and houses, lest its evil influence should be communicated to them; and in order still further to secure this object, the bull Nandi is placed sitting as a guardian between the Yonî and the inhabited site.82

Cow-worship assumes another form in connection with the theory of transmigration. It has become part of the theory that the soul migrates into the cow immediately preceding its assumption of the human form, and she escorts the soul across the dreaded river Vaitaranî, which bounds the lower world.

Cow-worship: Its Later Development

Though cow-worship was little known in the Vedic period, by the time of the compilation of the Institutes of Manu it had become part of the popular belief.

He classes the slaughter of a cow or bull among the deadly sins; “the preserver of a cow or a Brâhman atones for the crime of killing a priest;”83 and we find constant references in the mediæval folk-lore to the impiety of the Savaras and other Drâvidian races who killed and ate the sacred animal. Saktideva one day, “as he was standing on the roof of his palace, saw a Chandâla coming along with a load of cow’s flesh, and said to his beloved Vindumatî: ‘Look, slender one! How can the evil-doer eat the flesh of cows, that are the object of veneration to the three worlds?’

Then Vindumatî, hearing [231]that, said to her husband: ‘The wickedness of this act is inconceivable; what can we say in palliation of it? I have been born in this race of fishermen for a very small offence owing to the might of cows. But what can atone for this man’s sin?’”84

Re-birth through the Cow

When the horoscope forebodes some crime or special calamity, the child is clothed in scarlet, a colour which repels evil influences, and tied on the back of a new sieve, which, as we have seen, is a powerful fetish.

This is passed through the hindlegs of a cow, forward through the forelegs towards the mouth, and again in the reverse direction, signifying the new birth from the sacred animal. The usual worship and aspersion take place, and the father smells his child, as the cow smells her calf. This rite is known as the Hiranyagarbha, and not long since the Mahârâja of Travancore was passed in this way through a cow of gold.85

The same idea is illustrated in the legend of the Pushkar Lake, which probably represents a case of that fusion of races which undoubtedly occurred in ancient times. The story runs that Brahma proposed to do worship there, but was perplexed where he should perform the sacrifice, as he had no temple on earth like the other gods. So he collected all the other gods, but the sacrifice could not proceed as Savitrî alone was absent; and she refused to come without Lakshmî, Pârvatî, and Indrânî.

On hearing of her refusal, Brahma was wroth, and said to Indra: “Search me out a girl that I may marry her and commence the sacrifice, for the jar of ambrosia weighs heavy on my head.” Accordingly Indra went and found none but a Gûjar’s daughter, whom he purified, and passing her through the body of a cow, brought her to Brahma, telling him what he had done. Vishnu said: “Brâhmans and cows are really identical; you have taken her from the womb of a cow, and this may be considered a second birth.” Siva said: “As she has passed through a [232]cow, she shall be called Gâyatrî.”

The Brâhmans agreed that the sacrifice might now proceed; and Brahma having married Gâyatrî, and having enjoined silence upon her, placed on her head the jar of ambrosia and the sacrifice was performed.86

Respect Paid to the Cow

The respect paid to the cow appears everywhere in folk-lore. We have the cow Kâmadhenû, known also as Kâmadughâ or Kâmaduh, the cow of plenty, Savalâ, “the spotted one,” and Surabhî, “the fragrant one,” which grants all desires.

Among many of the lower castes the cow-shed becomes the family temple.87 In the old ritual, the bride, on entering her husband’s house, was placed on a red bull’s hide as a sign that she was received into the tribe, and in the Soma sacrifice the stones whence the liquor was produced were laid on the hide of a bull. When a disputed boundary is under settlement, a cow skin is placed over the head and shoulders of the arbitrator, who is thus imbued with the divine influence, and gives a just decision. It is curious that until quite recently there was a custom in the Hebrides of sewing up a man in the hide of a bull, and leaving him for the night on a hill-top, that he might become a spirit medium.88 The pious Hindu touches the cow’s tail at the moment of dissolution, and by her aid he is carried across the dread river of death.

I have more than once seen a criminal ascend the scaffold with the utmost composure when he was allowed to grasp a cow’s tail before the hangman did his office. The tail of the cow is also used in the marriage ritual, and the tail of the wild cow, though nowadays only used by grooms, was once the symbol of power, and waved over the ruler to protect him from evil spirits.

Quite recently I found that one of the chief Brâhman priests at the sacred pool of Hardwâr keeps [233]a wild cow’s tail to wave over his clients, and scare demons from them when they are bathing in the Brahma Kund or sacred pool.

The Hill legend tells how Siva once manifested himself in his fiery form, and Vishnu and Brahma went in various directions to see how far the light extended. On their return Vishnu declared that he had been unable to find out how far the light prevailed; but Brahma said that he had gone beyond its limits.

Vishnu then called on Kâmadhenû, the celestial cow, to bear testimony, and she corroborated Brahma with her tongue, but she shook her tail by way of denying the statement. So Vishnu cursed her that her mouth should be impure, but that her tail should be held holy for ever.89

Modern Cow-worship

There are numerous instances of modern cow-worship. The Jâts and Gûjars adore her under the title of Gâû Mâtâ, “Mother cow.” The cattle are decorated and supplied with special food on the Gopashtamî or Gokulashtamî festival, which is held in connection with the Krishna cultus. In Nepâl there is a Newâri festival, known as the Gâê Jâtra, or cow feast, when all persons who have lost relations during the year ought to disguise themselves as cows and dance round the palace of the king.90 In many of the Central Indian States, about the time of the Diwâlî, the Maun Charâûn, or silent tending of cattle, is performed.

The celebrants rise at daybreak, wash and bathe, anoint their bodies with oil, and hang garlands of flowers round their necks. All this time they remain silent and communicate their wants by signs. When all is ready they go to the pasture in procession in perfect silence. Each of them holds a peacock’s feather over his shoulder to scare demons. They remain in silence with the cattle for an hour or two, and then return home.

This is followed by [234]an entertainment of wrestling among the Ahîrs or cowherds. When night has come, a gun is fired, and the Mahârâja breaks his fast and speaks. The rite is said to be in commemoration of Krishna feeding the cows in the pastures of the land of Braj.91

During an eclipse, the cow, if in calf, is rubbed on the horns and belly with red ochre to repel the evil influence, and prevent the calf being born blemished. Cattle are not worked on the Amâvas or Ides of the month. There are many devices, such as burning tiger’s flesh, and similar prophylactics, in the cow-house to drive away the demon of disease. So, on New Year’s Day the Highlander used to fumigate his cattle shed with the smoke of juniper.92 Cow hair is regarded as an amulet against disease and danger, in the same way as the hair of the yak was valued by the people of Central Asia in the time of Marco Polo.93 An ox with a fleshy excrescence on his eye is regarded as sacred, and is known as Nadiya or Nandi, “the happy one,” the title of the bull of Siva.

He is not used for agriculture, but given to a Jogi, who covers him with cowry shells, and carries him about on begging excursions. One of the most unpleasant sights at the great bathing fairs, such as those of Prayâg or Hardwâr, is the malformed cows and oxen which beggars of this class carry about and exhibit.

The Gonds kill a cow at a funeral, and hang the tail on the grave as a sign that the ceremonies have been duly performed.94 The Kurkus sprinkle the blood of a cow on the grave, and believe that if this be not done the spirit of the departed refuses to rest, and returns upon earth to haunt the survivors.95 The Vrishotsarga practised by Hindus on the eleventh day after death, when a bull calf is branded and let loose in the name of deceased, is apparently an attempt to shift on the animal the burden of the sins of the dead man, if it be not a survival of an actual sacrifice. [235]

Feeling against Cow-killing

Of the unhappy agitation against cow-killing, which has been in recent years such a serious problem to the British Government in Northern India, nothing further can be said here. To the orthodox Hindu, killing a cow, even accidentally, is a serious matter, and involves the feeding of Brâhmans and the performance of pilgrimages. In the Hills a special ritual is prescribed in the event of a plough ox being killed by accident.96 The idea that misfortune follows the killing of a cow is common. It used to be said that storms arose on the Pîr Panjâl Pass in Kashmîr if a cow was killed.97

General Sleeman gives a case at Sâgar, where an epidemic was attributed to the practice of cattle slaughter, and a popular movement arose for its suppression.98 Sindhia offered Sir John Malcolm in 1802 an additional cession of territory if he would introduce an article into the Treaty with the British Government prohibiting the slaughter of cows within the territory he had been already compelled to abandon.

The Emperor Akbar ordered that cattle should not be killed during the Pachûsar, or twelve sacred days observed by the Jainas; Sir John Malcolm gives a copy of the original Firmân.99 Cow-killing is to this day prohibited in orthodox Hindu States, like Nepâl.

Bull-worship among Banjâras

There is a good example of bull-worship among the wandering tribe of Banjâras. “When sickness occurs, they lead the sick man to the foot of the bullock called Hatâdiya; for though they say that they pay reverence to images, and that their religion is that of the Sikhs, the object of their worship is this Hatâdiya, a bullock devoted to the god Bâlajî. On this animal no burden is ever laid, [236]but he is decorated with streamers of red-dyed silk and tinkling bells, with many brass chains and rings on neck and feet, and strings of cowry shells and silken tassels hanging in all directions.

He moves steadily at the head of the convoy, and the place he lies down on when tired, that they make their halting-place for the day. At his feet they make their vows when difficulties overtake them, and in illness, whether of themselves or cattle, they trust to his worship for a cure.” The respect paid by Banjâras to cattle seems, however, to be diminishing. Once upon a time they would never sell cattle to a butcher, but nowadays it is an every-day occurrence.100

Superstitions about Cattle

Infinite are the superstitions about cattle, their marks, and every kind of peculiarity connected with them, and this has been embodied in a great mass of rural rhymes and proverbs which are always on the lips of the people.

Thus, for instance, it is unlucky for a cow to calve in the month of Bhâdon. The remedy is to swim it in a stream, sell it to a Muhammadan, or in the last resort give it away to a Gujarâti Brâhman. Here may be noticed the curious prejudice against the use of a cow’s milk, which prevails among some tribes such as the Hos and some of the aboriginal tribes of Bengal. The latter use a species of wild cattle, the Mithun, for milking purposes, but will not touch the milk of the ordinary cow.101

The Buffalo

The respect paid to the cow does not fully extend to the buffalo. The buffalo is the vehicle of Yama, the god of death. The female buffalo is in Western India regarded as the incarnation of Savitrî, wife of Brahma, the Creator. [237]Durgâ or Bhavânî killed the buffalo-shaped Asura Mahisa, Mahisâsura, after whom Maisûr is called. According to the legend as told in the Mârkandeya Purâna, Ditî, having lost all her sons,