Pan, weaving caste

Contents |

Pan

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

Pamoa, Panr, Pab, Panika, Chik, Chik-Baraik, Baraik, Ganda, Mahato, Sauasi, Tanti, a low weaving, basket-making, and servile caste scattered under various names throughout tbe north of Orissa and the southern and western parts of Chota Nagpur. "In feature," says Colonel Dalton, "these people are Aryan or Hindu rather "than Kolarian or Dravidian. Their habits are all much alike, "repudiating the Hindu restrictions upon food, but worshipping "Hindu gods and goddesses, and having DO peculiar customs which " stamp them us of the other races. 1" In Singbhum they are said by the same authority to be "domesticated as essential consti¬tuents of every Ho village community," aud "now almost undis¬tinguishable from the Hos.2" In another place they are described as " in all probability remnants of the Aryan colonies that the Hos subjugated.3 "

From these somewhat contradictory utterances it is not quite easy to gather what was Oolonel Dalton's final opinion as to the origin of the Pans. In one place he credits them with features of an Aryan or Hindu type, in another he speaks of them as almost undistinguishable from the Hos-the most markedly Negrito-like representatives of the Dravidian race. The distinction between Kolarian and Dravidian mentioned by him is of course purely linguistic, as has been explained in the introduction to these volumes.

I Dalton, Ethnolo.oy of Bengal, p. 325.

2 Dalton, op. cit., ]96, 25.

3 Dalton, Gp. cit., p. ]85.

The suggestion that the Pans may be the remnants of Aryan colonies subjugated by the Hos takes us back into prehistoric times, and raises the probably insoluble question: Were there ever Aryan colonies in the region where we find the Pans; and if so, is there any-thing to show that the HoS' subj ugated them? To the best of my knowledge the only evidence for the existence of such colonies consists of certain soanty architectural remains buried here and there in the jungles of Chota Nagpur, and of the shadowy tradition that the Singbhum copper mines were worked by the J ains. Tbis seems a slender foundation for the conjecture that the Pans of the present day are the descendants of prehistoric Aryan colonists who were subdued by the Dravidian races of Chota Nagpur and settled down as helots in communities of alien blood, retaining¬their religion, but parting with that purism in matters of food which has always distinguished the Aryan in comparison with the Dasyu ..

Traditions

Fortunately there is no necessity to enter upon this speculative line of inquiry. Not only do their own tradi¬ tions claiming descent from the snake throw doubt on the Aryan pedigree whioh has been made out for them, but the most cursory examination of the exogamous divisions of the Pans affords convincing evidence of their Dravidian origin. The caste has a very numerous set of totems, comprising the tiger, the buffalo, the monkey, the tortoise, the cobra, the mon ¬goose, the owl, the king-crow, the peacock, the centipede, various kinds of deer, the wild fig, the wild plum, and a host of others which I am unable to identify. They have in fact substantially the same set of totems as the other Dravidian tribes of that part of the country, and make use of these totems for regulating .marriage in precisely the same way. The totem follows the line of male descent. A man may not marry a woman who has the same totem as himself, but the totems of the bride's ancestors are not taken into account, as is the case in the more advanced forms of exogamy. In addition to the prohibition of marrying among totem kin, we find a b ginning of the supplementary system of reokoning prohibited degrees. 1'he formula, however, is curiously incomplete. Instead of mentioning both sets of uncles and aunts and barring seven generations, as is usual, the Pans mention only the paternal uncle and exclude only one generation. They are therefore only a stage removed from the primitive state of things when matrimonial relations are regulated by the simple rule of exogamy, and kinship by both parents has not yet come to be recognized. Like most castes which are spread over a large area of country, the Pans appear under several different names, the origin of It is a singuiar fact that the tiger gives its name to two separate groups. One of these is called Kulllai. a word which must have denoted tiger in the original language of the Pans (compare the Santali Kulh) j while the other, B6ghail, is obviously of Hindi origin. whioh it is now diffioult to trace. Thus in Manbhum they call them¬selves Baraik. 'the great ones,' a title used by the Jadllbansi Rajputs, the Binjbias, Rautias, and Kbandaits ; in Western Lobardaga and Sarguj it we meet them under the name of Ch ik or Ch ik Barai k i in Singbhum they are Sawasi or Tanti, and in the Western Tribu¬tary Statcs they are called Ganda, a name which suggests the possibility of descent from the Gonds, a tribe which in former times appears to have extended further to tbe east, and to have occupied a more dominant position than is the case at the present day.

Internal structure

In Orissa five sub-castes areknown:-(l) Orh-Pan or Uriya-Pan, a semi-Hinduised group supposed to have sprung £rom a liaison between a Pan woman and a member of one of the lower Uriya castes, but now claim¬ing a higher social status than the PallS of the original stock; (2) Buna-Pan, including those Pans who weave cloth only; (3) Betra-Pan or Raj-Pan, basket-makers and workers in cane, also employed as musicians, syces, and chaukidars. (4) Pim-Baistab, com¬posed of Pans who have become Vaishnavas and who officiate as priests for their own caste. As a general rule it may be laid down that religious differences within the pale of Hinduism do not lead to the formation of endogamous groups. Among Agarwals and Oswals Jains and Hindus intermarry. Itis only in Orissa that the Vaishnava members of several castes seem to cut themselves offfrom their own caste and from the general body of Vaishnavas, and form a new sub-oaste undM a double name denoting the origin of the groups. (5) Patradia, consisting of those Pans who live in the villages of the Kandh tribe, work as weavers and perform for the Kandhs a variety of servile functions. Tbe group seems also to include the descendants of Pans, who sold themselves as slaves, or were sold as Merias or victims to the Kandhs. The precise history of the Patradia sub-caste is of course obscure, but I see no reason to doubt the possibility of an endogamous group being formed in the manner alleged. There is no question whatever as to the Pans occupying a separate quarter,¬a kind of Ghetto,-in the Kandh villages, where they weave the cloth that the tribe requires, and also work as farm-labourers, cultivatincr Jand belonging to the Kandhs, and making over to their landlord~ balf the produce as rent. . These Pans naturally come to be looked down upon by other Pans who serve Hindus or live in villages of their own and then come to be ranked as a separate sub-oaste as regards the slave class all~ged to be. illcl~ded in the group. We know that an extenslve traffic m chlldren de ltined for human sacrifice used to go on in the Kandh cou ntry, and that the Pans were the agents who "sometimes purch'11ed, but more frequently kidnapped, the children, whom they sold to the Kandhs, and were so debased that they occasionally sold their own offspring, though they knew of course the fate that awaited them." Moreover, apart from the demand for sacrificial purposes, the practice of selling men as agricultural labourers was untIl a few years ao-o by no means uncommon in the wilder parts of tile Chota N acrp~r Division, where labour is scarce and cash payments are ahnost unknown. Numbers of formal bonds have come before me whereby

men sold not only themselves, but their children for a lump sum to enable them to marry, and on several occasions attempts have been made to enforce such contracts in the courts, and to prevent the Kamia, as a slave of this class is called, ITom emigrating to the tea districts of Assam, or n:om otherwise evading the obligations he had taken upon himself. There is nothing therefore antecedently improbable in the existence of a slave sub-caste among the Pans.

Marriage

Pan girls are usually married atter they are fully grown up, and the Hindu practice of infant-marriage is confined to a few well-to•do members of the Orh-Pan sub-caste, who have borrowed it from their orthodox neighbours as a token of social respectability. The standard bride-price is said to be Rs. 2 in cash, a maund and a half of husked rice, a goat aud two saris-one for the bride aud one for her mother-in-law. In Orissa the simple marriage ceremony in vogue is performed by a member of the Pan-Vaishnava sub-caste, who, as has been mentioned above, serve the Pans as priests, and are often spoken of inaccurately as their "Brahmans." In Chota Nagpur, where the organization of the caste is less elaborate than in Orissa, men of the Nageswar caste not unfrequently serve the Pans as priests; or again any member of the caste with a turn for cere¬monial functions may officilLte, and the post is usually filled by a Bhakat or devotee. '1'he most essential portions of the ritual are believed to be sindw'dan, the smearing of vermilion on the bride's forehead, and the parting of her hair and tying together the hands of the bride and bridegroom. The widows may marry a second time, and it is deemed the proper thing for her to marry her deceased husband's younger brother. She may in no case marry the elder brother. Divorce is permitted, for almost any reason, with the sanction of the caste pancMyat. In Orissa the headman of the caste, styled Dalai or Behera, presides on such occasions, and a cMrida-patra or bill of divorcement is drawn up. The husband is also required to provide her with food and clothing tor six months. Divorced wives are allowed to marry again.

Religion

The professed religion of the Pans is a sort of bastard Hindu¬ ism, varying with the locality in which they happen to be settled. In Orissa and Singbhum they incline to Vaishnavism, and tell a silly story about their descent from Duti, the handmaiden of Radha, while in Lohardaga the worship of MaMdeva and Devi Mai is more popular. This veneer of Hinduism, however, has only recently been laid on, and we may discern underneath it plentiful traces of the urimitive animism common to all the Dravidian tribes. Man is surrounded by unseen powers-to call them spirits is to define too closely-which need constant service and propitiation. and visit a negligent votary with various kinds of diseases. The Pans seem now to be shuffiing off this uncomfortable creed and deserting their anClent gods, while as yet they have not taken vigorously to Hinduism, aud they are described by one observer as having very little religion of any kind. Among the minor gods in vogue among them mentioll may be mane of Pauri Pahal'i or Bar-Pahar, a divinity of unques¬tionably Dravidian origin, who inhabits the highest hill in the neighbourhood and demands the sacrifice of a he-goat in the month of Pbalgun, and occasional offerings of ghi all the year round. '1'he snake is also worshipped as the ancestor of the caste. An attempt was made recently by the Pans of Moharbhanj to induce Brahmans to officiate for them as priests at marriages and funeral ceremonies, but no Brahmans could be persuaded to undertake these offices.

Disposal of the dead

The southern Pans usually bury their dead in Orissa with the bead pointing to the east, while in Sing¬ bhum it is turned towards the north. In Lohardaga both cremation and burial are in vogue. Rape seed and water are offered to the deceased and to his ancestors on the eleventh day after death.

Social status and occupation

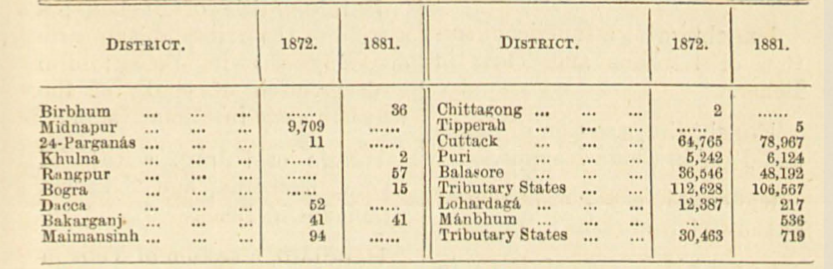

The sooial status of the caste according to Hindu ideas is exceedingly low. They eat beef, pork, and fowls, drink wine, and regard themselves as better than the H ari in virtue of their abstain¬ iug from horse flesh. In Lohardaga they eat kacM, drink and smoke with Mundas and Oraons. Their original oocupation is admitted to be weaving, but many of them have now taken to oulti¬ vation. The Buna Pans of Orissa are noted thieves. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Pans iu 1872 and 1881;¬