Port Blair

Contents |

Port Blair, 1908

Physical aspects

A Penal Settlement in the Andaman Islands, Bay of Bengal, which consists of the South Andaman and the islets attached thereto, covering an area of 473 square miles. Of this total, 327 square miles are in actual occupation. The unoccupied area consists of the densest jungle. The occupied area is partly cleared for cultivation, grazing, and habitation, and aspects partly afforested. A great part of the unoccupied area is in the hands of the hostile Jarawas ; but they are gradually retreating northwards under pressure of the forest operations, which are extending over the whole area of the Penal Settlement.

The South Andaman Island has a very deeply indented coast-line, comprising the following harbours : on the east coast, Port Meadows and Port Blair ; on the south coast, Macpherson's Strait ; on the west coast, Port Mouat, Port Campbell, and Port Anson. Vessels of large draught can anchor and trade with safety in these in any weather and at all seasons. If Baratang be reckoned with the South Andaman as a natural apanage, Elphinstone Harbour must be added to the list. Smaller vessels also find the following places safe for shelter and most convenient for work : on the east coast, Colebrooke Passage, Kotara Anchorage, and Shoal Bay ; on the west coast, Elphinstone Passage in the Labyrinth Islands, and in some seasons Constance Bay ; in Ritchie's Archipelago, Kwangtung Strait and Tad ma Juru, and in some seasons Outram Harbour.

For forest trade, the staple commerce of the islands, a more con- venient natural arrangement is hardly imaginable. Port Mouat is only 2 miles distant from Port Blair, over an easy rise ; Shoal Bay is 7 miles, with an easy gradient from Port Blair, and runs into Kotara Anchorage ; and Port Meadows is but a mile from Kotara Anchorage. Creeks navigable by large steam-launches run into Port Blair from some dis- tance inland. Five straits surround the island : two, Macpherson's Strait and Elphinstone Passage, navigable by ships; and the rest, Middle Strait, Colebrooke Passage, and Homfray's Strait, navigable by large steam-launches. Diligent Strait, practicable for the largest ships, and only 4 miles across at the narrowest point, separates Ritchie's Archipelago from the main islands ; and the archipelago is itself intersected everywhere by straits and narrows, which are mostly navigable.

The whole of the Settlement area consists of hills separated by narrow valleys, rendering road-making and rapid land communication difficult. The main ranges are the Mount Harriett Range, up to 1,500 feet; the Cholunga Range, up to 1,000 feet; and the West Coast Range, up to 700 feet. These run almost parallel, north and south, down the centre of the island. To the north, the Cholunga Range breaks up into a number of more or less parallel ridges. To the south, below Port Blair Harbour, the country is a maze of hills rising to 850 feet, and tending to form ridges running north and south.

No stream in the island could be called a river, and on the cast coast perennial streams are not common. On the west and north, however, more surface water is found, and perennial streams running chiefly from south to north are fairly numerous. Fresh water is, how- ever, everywhere obtained without much difficulty from wells, and rain-water reservoirs (tanks) could be formed in all parts. Navigable salt-water creeks are numerous, and are of much assistance in water- carriage.

History

The old settlement at the Andamans, established by the well-known Marine Surveyor Archibald Blair in 1789, was not a penal settlement at all. It was formed on the lines of several then in existence, e.g. at Penang and Bencoolen, to put down piracy and the murder of shipwrecked crews. Convicts from India were sent incidentally to help in its development, precisely as they were sent to Bencoolen, and afterwards to Penang, Malacca, Singapore, Moulmein, and the Tenasserim province. Everything that Blair did was performed with ability ; and his arrangements for estab- lishing the settlement in what he named Port Cornwallis (now Port Blair) were excellent, as were his selection of the site and his surveys of parts of the coast, several of which are still in use. The settlement flourished under Blair; but unfortunately, on the advice of Commodore Cornwallis, brother of the Governor-General, the site was changed for strategical reasons to North-East Harbour, now Port Cornwallis, where it flourished at first, but subsequently suffered much from sickness. Here it was under Colonel Alexander Kyd, an engineer officer, and a man of considerable powers and resource. On the abandonment of the settlement in 1796, on account of sickness, it contained 270 convicts and 550 free Bengali settlers. The convicts were transferred to Penang and the settlers taken to Bengal. After that the islands remained unoccupied by the Indian Government till 1856, the present Penal Settlement being formed two years later.

Since its foundation, the history of the Penal Settlement is merely one of continuous official development from March, 1858 (when Dr. P. J. Walker, an experienced Indian Jail Superintendent, arrived with 4 European officials and 773 convicts, and commenced clearings in Port Blair Harbour), to the present day.

The penal system in force at the Andaman s is sui generis, has grown up on its own lines, and has been gradually adapted to the require- ments of the present complex conditions. The system has always been independent of, and was never at any time based on, the Indian prison system, and has been continuously under development from its inception by Sir Stamford Raffles for about a hundred years. The fundamental principles on which it is founded are still substantially what they were originally, and have stood the criticism, the repeated examination, and the modifications in detail of a century without material alteration. The classification of the convicts, the titles of those who are selected to assist in controlling the general body, the distinguishing marks on their costume, the modes of employing them, and their local privileges are virtually now as they were at the beginning.

The first temporary Superintendent of the Andamans was Captain (afterwards General) Henry Man, who had long been Superintendent of the Penal Settlements in the Straits. In January, 1858, he was authorized by the Government of India to follow generally the system in force in the Straits Settlements, and received powers under the Mutineers Acts, XIV and XVII of 1857 (since repealed). Captain Man was succeeded in March, 1858, by Dr. P. J. Walker, who drew up rules, sanctioned by the Government of India, which were based on instructions identical with those given to Captain Man. These were followed by the Port Blair and Andamans Act, XXVII of 1861 (since repealed), and by modifications in the rules made by successive Superintendents and by Lord Napier of Magdala, as the result of an official inspection of the Settlement in 1863. In 1868, when General Man became permanent Superintendent, he embodied in the Andaman system the Straits Settlements Penal Regulations, and thus brought the system still more closely into line with that of the Straits Settlements. These modifications still affect almost every part of it. A formal Regulation was drafted in 1871, and after discussion by Sir Donald Stewart, Chief Commissioner and Superintendent, Mr. (Justice) Scarlett Campbell, and Sir Henry Norman, became the Andaman and Nicobar Regulation, 1874, supplemented by rules passed by the Governor- General-in-Council and the Chief Commissioner. In 1876 a new Andaman and Nicobar Regulation was drawn up, but the rules under the Regulation of 1874 were continued. These rules, together with the Superintendent's by-laws (Settlement Standing Orders) passed under them, and modified from time to time by the Government of India and by the Commission of Sir C. J. Lyall and Sir A. Leth- bridge in 1890, form the still-growing penal system of the present day.

The methods employed were originally a new departure in the treat- ment of prisoners, the salient features being the employment of con- victs on every kind of labour necessary to a self-supporting community, and their control by convicts selected from among them. Permission to marry and settle down is given after a certain period, when the convict is called a ' self-supporter.' Indian convicts were first trans- ported in 1787 to Bencoolen in Sumatra to develop that place, then under the Indian Government. The Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Stamford Raffles, drew up a dispatch in 1818, explaining the principles he had already successfully adopted for their management; and in 1823 he sent the Government a copy of his Regulations. In 1825 Bencoolen was ceded to the Dutch, and the convicts were transferred to Penang and Singapore. Penang had been occupied in 1785, and convicts were sent there in 1796. When the Bencoolen convicts arrived, they remained under the Regulations of Sir Stamford Raffles, and in 1827 the Penang Rules were adapted from these. When Malacca was occupied in 1824, convicts were sent there from Penang, and shortly afterwards they too were placed under the Penang Rules. Singapore had been founded by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819; and in 1825 convicts arrived there from Bencoolen and India, and in 1826 from Penang. The Bencoolen Rules, and later the Penang Rules, were in force at Singapore, with modifications, for many years, until Regu- lations for the management of Indian convicts were drawn up in 1845 by Colonel Butterworth, the Governor of Singapore, known as the Butterworth Rules. They were modified by Major McNair, Superin- tendent of the convicts, in 1858. The Butterworth Rules were founded on the principles laid down by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1818 and on his Bencoolen Rules. A leading part in the drafting and working of these was taken by General Man, to whom it fell to start the Andaman Penal Settlement in 1858. He carried them with him to Moulmein and the Tenasserim province, to which places Indian convicts were also trans- ported ; and when he was appointed permanent Superintendent of the Andaman Penal Settlement in 1868 he embodied the Regulations for Tenasserim in the rules and orders he found already existing. The intimate connexion of the Andamans with the original penal system from the beginning is further illustrated by the fact that, when the old settlement at Port Cornwallis was broken up in 1 796, the convicts were transferred to Penang.

The Penal Settlement is administered by the Chief Commissioner, Andamans and Nicobars, as Superintendent, with a Deputy and a staff of Assistant Superintendents and overseers, who are almost all Europeans, and sub-overseers, who are natives of India. The petty supervising establishments are staffed by convicts. There are, besides, special departments Police, Medi- cal, Commissariat, Forests, Tea, Marine, &c., of the usual type in India, except that all civil officers are invested with special powers over convicts. Civil and criminal justice is administered by a series of courts under the Chief Commissioner and the Deputy-Super- intendent, as the principal courts of original and appellate juris- diction. The Chief Commissioner is also the chief revenue and financial authority.

The Penal Settlement centres round the harbour of Port Blair, the administrative head-quarters being on Ross Island, an islet of less than a quarter of a square mile, across the entrance of the harbour. For administrative purposes it is divided into two Districts and four sub- divisions. The subdivisions remain constant, but their distribution between the Districts has varied from time to time. At present they are as follows : Eastern District (head-quarters, Aberdeen) Ross, Haddo ; Western District (head-quarters, Viper Island) Viper, Wim- berley Ganj.

Within the subdivisions are stations, places where labouring convicts are kept, and villages, where either ' free ' settlers or ' self-supporters ' dwell. As these stations and villages enter largely into the life and description of the place, a list is given here.

Persons transported to Port Blair by the Government of India are either murderers who for some reason have escaped the death penalty, or perpetrators of the more heinous offences against the person and property. Their sentences are chiefly for life ; but some, varying from very few to a considerable number, with long-term sentences, are also sent from time to time. Except under special circumstances, con- victs are not received under eighteen years of age, nor over forty, and they must be certified as medically fit for hard labour before trans- portation. Youths between eighteen and twenty are kept in the boys' gang under special conditions. Girls of about sixteen are occasionally received ; but as all women locally unmarried are kept in the female jail, a large enclosure consisting of separate sleeping wards and work- sheds, there are no special rules for them.

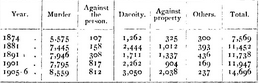

The following table shows that murder and heinous offences against the person, dacoity (gang robbery with murder or preparation for murder), and other heinous offences against property, make up nearly the whole total :

These figures illustrate clearly the violent character of the convicts, and it is of value to examine their behaviour under continuous restraint. Between 1890 and 1900, the average proportion of convicts who com- mitted or attempted murder was 0-12 per cent., the figures rising to 0.154 in 1894. Neither the nature of the labour nor the discipline enforced appears to have any effect on the tendency to murder, and the motives traced are similar to those disclosed among an ordinary population, while murderous assaults are usually committed quite sud- denly on opportunity and cause arising.

The full penal system, as at present worked, is as follows. Life- convicts are confined in the cellular jail for six months, where the discipline is severe but the work is not hard. They are then put to hard gang labour in outdoor work for 4-J years, and are locked up at night in barracks. For his labour during this period the convict receives no reward, but his capabilities are studied. During the next five years he remains a labouring convict, but is eligible for the petty posts of supervision and the easier forms of labour ; he also gets a very small allowance for little luxuries, or to deposit in the special savings bank. He has now completed ten years in transportation, and can receive a ticket-of-leave, being termed a ' self-supporter.' In this condition he earns his own living in a village ; he can farm, keep cattle, and marry or send for his family. But he is not free, has no civil rights, and cannot leave the Settlement or be idle. After twenty to twenty-five years spent in the Settlement with approved conduct, he may be released either absolutely or, in certain cases, under con- ditions as to place of residence and police surveillance. While a ‘ self- supporter,' he is at first assisted with house, food, and tools, and pays no taxes or cesses ; but after three to four years, according to certain conditions, he receives no assistance, and is charged with every public payment which would be demanded of him were he a free man.

The women life-convicts are similarly dealt with, but less rigorously. The general principle is to divide them into two main classes : those in, and those out of, the female jail. Every woman must remain in the female jail unless in domestic employ by permission, or married and living with her husband. Women are eligible for marriage or domestic employ after five years in the Settlement, and if married they may leave the Settlement after fifteen years with their husbands ; but all married couples have to wait till the expiry of both their sentences, and they must leave together. If unmarried, women remain twenty years in the jail. They rise from class to class, and can become petty officers on terms similar to those for the men.

Term-convicts are treated on the same general lines, except that they cannot become ‘ self-supporters,' and are released at once on the expiry of their sentences.

Convict marriages, which are described below under Caste, are carefully controlled to prevent degeneration into concubinage or irregular alliances ; and the special local savings bank has proved of great value in inducing a faith on the part of the convicts in the honesty of the Government, besides its value in causing habits of thrift and diminishing the temptation to violence for the sake of money hoarded privately.

The whole aim of the treatment is to educate for useful citizenship, by the insistence on continuous practice in self-help and self-restraint, leading to profit Efforts to behave well and submission to control alone guide the convict's upward promotion ; every lapse retards it. And when he becomes a ' self-supporter,' the convict can provide money out of his own earnings as a steady member of society, to afford a sufficient competence on release. The incorrigible are kept till death, -the slow till they mend their ways, and only those who are proved to have good in them return to their homes. The argument on which the system is based is that the acts of the convict spring from a constitutional want of self-control.

All civil officers in the Settlement are Magistrates and Civil Judges, with the ordinary powers exercised in India; and if a term-convict misbehaves seriously, his case can be tried magisterially and an addi- tional punishment inflicted. In the case of a life-convict, any sentence of ' chain gang ' that may be imposed is added to the twenty (or twenty-five) years that he must, in any case, remain. Any offence under the Indian Penal Code or other law is punishable executively as a 'convict offence; except an offence involving a capital sentence, which is tried at Sessions in the ordinary manner. ' Convict offences' though punishable executively, are all tried, however trivial, by a fixed cuasi-judicial procedure, including record and appeal, so that the con- vict is made to feel that justice is as secure to him as to the free.

The convicts, while in the Settlement, are divided in several ways. The great economic division for both sexes is into labouring convicts and * self-supporters ' ; the former perform all the labour of the place, skilled and unskilled, and the latter are chiefly engaged in agriculture and food supplies. The commissariat division is into l rationed' and 4 not rationed ' ; in the former class are nearly all the labouring convicts, and in the latter all the ' self-supporters ' and some of the labouring convicts. The financial division is into classes indicating those with and those without allowances, with numerous subdivisions according to the scale of allowances.

There are 1 also disciplinary gangs, involving degradation either on account of bad character on arrival, or while in the Settlement. These are known as Cellular Jail Prisoner, Chain Gang, Viper Jail Prisoner, Habitual Criminal Gang, Viper Island Disciplinary, Unnatural Crime Gang, Chatham Island Disciplinary, ' D ' (for ' doubtful ') ticket men. The * D ' ticket may be explained as follows. Prisoners in the third class are obliged to wear wooden neck tickets, bearing full particulars of their position. On the ticket is the convict's number, the section of the Indian Penal Code under which he was convicted, the date of his sentence, and the date his release is due. For a convict of ' doubtful ' character the ticket has a D ; for one of a gang of criminals convicted together it has a star, and the presence or absence of A shows the class of ration ; for a life-prisoner it has L.

There is a class of ' connected ' convicts. Prisoners convicted in the same case, marked by a star on the neck ticket, are all specially noted and never kept in the same station or working gang. These special arrangements sometimes involve considerable care and organization, as a gang of dangerous dacoits may arrive in Port Blair forty strong.

The Settlement is divided into what are known as the 'free' and 'convict' portions, by which the free settlers living in villages are separated from the * self-supporters ' who also live in villages. Every effort is made to prevent unauthorized communication between these two divisions. No adult person can enter the Settlement without permission, or reside there without an annual licence ; and certain other necessary restrictions are imposed on him as to his movements among and his dealings with the convicts, on pain of being expelled or punished. The 'free' subdivisions are Ross, Aberdeen, Haddo, and Garacherama. The * convict' subdivisions are Viper and Wimberley Ganj.

A large proportion of the free settlers are descendants of convicts (known in Port Blair as the * local-born ') and permanent residents. Like every other population the 'local-born' comprise every kind of personal character. Taken as a class they may, however, be described thus. As children they are bright, intelligent, and unusually healthy. It is the rule, not the exception, for the whole of a ' local-born ' family to be reared. On the score of intelligence they do not fail throughout life. As young people they do not exhibit any unusual degree oi violence or inclination to theft, but their general morality is distinctly low. Among the girls, even when quite young, there is a painful amount of prostitution, open and veiled : the result partly of temptation in a population in which the males very greatly preponderate, but chiefly due to bad early associations, convict mothers not being a class likely to bring up their girls to a high morality. The boys, and some- times the girls, exhibit much defiant pride of position, in being free as opposed to the convict, combined with a certain mental smartness, idleness, dislike of manual labour, and disrespect for age and authority that stand much in their way in life. Their defiant attitude is probably due to the indeterminate nature of their social status, as has been observed of classes unhappily situated socially elsewhere. Heredity seems to show itself in both sexes rather in a tendency towards the meaner qualities than towards violence of temperament. The adult villagers are quarrelsome and as litigious as the courts will permit them to be. They borrow all the money they can, do not get as much out ol the land as they might, and spend too much time in attempting to get the better of neighbours. At the same time, it would be an entire error to suppose that the better elements in human nature are not exhibited, and many convicts' descendants have shown themselves upright, capable, hardworking, honest, and self-respecting. On the whole, considering their parentage, the ‘ local-born' population is oi a much higher type than might be expected, though there is too great a tendency on the part of the whole population to lean on the Government, the result probably of the minute supervision necessary in the conditions of the Settlement.

population

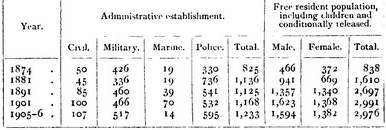

The population of the Penal Settlement consists of convicts, their guards, the supervising, clerical, and departmental staff, with the families of the latter, and a limited number of ex convict and trading settlers and their families, Detailed statistics have been maintained since 1874, and are shown in the tables on the next page; but it must be remembered that in intervening years the numbers of the convicts may vary con

siderably.

The mother tongues of the population are as numerous as in the parts of India and Burma from which it is derived ; but the linguk franca of the Settlement is Urdu (Hindustani), spoken in ever) possible variety of corruption, and with every variety of acceiit All convicts learn it to an extent sufficient for their daily wants and the understanding of orders and directions. It is also the ver- nacular of the ‘local-born, whatever their descent. The small extent to which many absolute strangers, such as the Burmans, the inhabitants of Madras, and others, master it, is one of the safeguards of the Settle- ment, as it makes it impossible for any general plot to be batched. In barracks, in boats, and on works where men have to be congregated, every care is taken to split up nationalities, with the result that, except on matters of daily common concern, the convicts are unable to con- verse confidentially together. The Urdu of Port Blair is thus not only exceedingly corrupt from natural causes, but it is filled with technicali- ties arising out of local conditions and the special requirements of convict life. Even the vernacular of the ' local-born ' is loaded with them. These technicalities are partly derived from English, and are partly specialized applications to new uses of pure or corrupted Urdu words. As opportunity has arisen, some of these have been collected and printed from time to time in the Indian Antiquary. The most prominent grammatical characteristic of this dialect appears in the numerals, which are everywhere Urdu, but are not spoken correctly.

The conditions under which the people live are so artificial and so unlike those of an ordinary community that it is impossible to describe them on the usual lines. There are hardly any natural movements to observe and report. The following remarks aim at a description of the social state of the convicts and of the unofficial population in the regulated conditions of life imposed on them.

The restrictions under which the free residents live have a distinct effect on the characters of those subjected to them from childhood to death, an effect which will become more and more apparent as generation after generation of convicts' descendants come under their pressure. They include Government establishments introduced from India, traders from India and Burma, domestic servants who have accompanied their masters, very few settlers from outside, and the descendants of convicts who have settled in the Penal Settlement after their release.

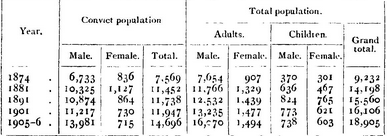

General convict statistics for a series of years are given below :

In this table the ' escaped ' are those who have not been heard of again. As a matter of fact, such unfortunates, as a rule, die in the jungles or are drowned at sea. Very rarely does a convict escape to the mainland.

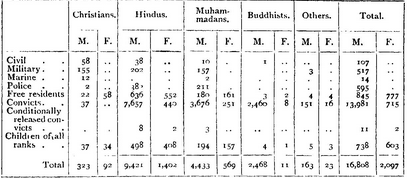

At the Census of 1901 the population of Port Blair was distributed over an occupied area of 327 square miles in 29 'stations/ or places where labouring convicts are kept, and 34 ‘ villages, 7 or places where free residents or ticket-of-leave convicts (' self-supporters ') reside. The population then numbered 16,256, including 150 persons 114 males and 36 females on the mail steamer. Details of the population on March 31, 1906, are shown in the table on the next page.

Every religion in India is represented among the convicts, but it was impossible to classify Hindus by sect. The Sikhs are represented chiefly in the military police battalion, the Buddhists by the Burman convicts, and the Christians by the British infantry garrison and the officials. It may be noticed that not one person was returned as a Jew among all the convicts.

The necessary work of the Settlement is all performed by convicts. Omitting those employed as public servants, the ex-convict and free unofficial population is chiefly supported by agriculture, which was recorded as the mearis of subsistence of 57 per cent.

As the maintenance of caste among natives of India involves the maintenance of respectability, and as the aim of the penal system is the resuscitation of respectability among the convicts, nothing is per- mitted that would tend to destroy the caste feeling among them. The tendency as usual is to raise their caste wherever that is possible, and occasionally some crafty scoundrel is convicted of illegitimate associa- tion with fellow Hindus. Two Mehtars (sweepers) were some time ago detected in successfully managing this : one, a ' self-supporter,' masque- raded for years in his village as a Rajput (Rajvansi), and another for years was cook to a respectable Hindu free family on the ground of being a Brahman. It is also not at all uncommon for low-caste ex-convict settlers to adopt a mode of dress and life which would be quite inadmissible if they were to return to their native villages. In Port Blair, as elsewhere, the great resort of those desiring to raise their social status is the adoption of Islam. On the other hand, instances have occurred in which men who were not so by caste have volunteered to become Mehtars, debasing their social status in order to adopt what they regarded as a less arduous mode of life than cooly labour.

Considerable ethnographic interest attaches to the descendants of convicts, as a marked difference is maintained at present between the free introduced from India and the free with the taint of convict blood. In certain cases the barrier is broken down socially, but entry by marriage into a ' local-born ' family is regarded as degrading to an immigrant from India. How long this will last, and in what 'direc- tions the barrier will be habitually broken through, is worth watching. At present there is much greater sympathy on the part of the im- migrants, temporary or permanent, with the actual convicts than with their descendants.

Although the ' self-supporter ' is entitled to send for his family from India, he very seldom does so, or it may be that the families are seldom willing to join convicts ; and the result is that the ‘ local-born ' are nearly all the descendants of convict marriages. Any ' self-supporter ' may marry a convict woman from the female jail, if he has the permis- sion of the Settlement authorities and the marriage is in accordance with the social custom of the contracting parties. In practice, an inquiry ensues on every application, covering the eligibility of the parties to marry under convict rules, the capacity of the man to support a family, and the respective social conditions in India of both parties. A Hindu would not be allowed to marry a Muhammadan woman, while an un- divorced Muhammadan woman with a husband living in India would not be allowed to marry at all, and so on. When the preliminaries have been settled, often after prolonged inquiry, permission is registered by the Superintendent, who then calls upon the parties to appear before him and certify, on a given date, that they have been actually married according to their particular rite. The marriage is registered by the Superintendent and becomes legal. Owing to the enormous variety of marriage rites in India, the statement of the parties that the appropriate ceremonies have been performed is accepted. In carrying out this prac- tice there is no difficulty as regards Christians, Muhammadans, and Buddhists, endogamy within their group being easily ensured; but some difficulty has arisen as regards Hindus. Customs among Hindus differ indefinitely, not only in every caste but with every locality ; and as the convicts come from various castes and localities, in the strict view of the question hardly any Hindu marriage contracted in Port Blair could be in accordance with custom, which, be it noted, is a different question from legality. In the Settlement, however, the knot has been cut since 1881 by recognizing only the four main divisions (varna) of Hindus as separate castes, within which there must be endogamy among the Hindu convicts : namely, Brahmans, Kshattriyas, Vaisyas, and Sudras. Before 1881, under pressure of the dominating conditions, the rule was merely Hindu to Hindu, Muhammadan to Muhammadan, Chris- tian to Christian; Buddhists and others hardly came into consideration.

The birth and growth of caste among convicts' descendants is thus a question of the growth and formation of new or special local Hindu castes, which can be studied obscurely in every part of India, and clearly enough in all regions where a Hindu propaganda is being carried among indigenous and animistic populations in the course of the natural spread of civilization along new lines of communication. In Port Blair the caste feeling exists as distinctly, within limits, among the ' local-born' Hindus, as it does elsewhere among the natives of India ; and the interest of the question lies in observing how the people have settled the relative social status of the descendants of what, in India, would be looked on as the offspring of mixed castes ; for fond as they are of talking of their caste and claiming it, the ' local-born ' have but hazy ideas on the subject as it is understood in the localities from which their parents came. They take into consideration only the caste of the father, as they understand it, that of the mother being ignored. Having introduced this great innovation into custom, they divide them- selves into high and low castes ; the children of Brahman, Kshattriya, and Vaisya fathers holding themselves, so far as they can, to be of high caste and apart from the whole of the innumerable castes coming under the head of Sudra or low caste. Then a ' local-born ' man marries, if possible, the daughter of a man of the same caste as his own father. Thus is a full caste system like that of India being developed among the descendants of the convicts.

The present customs connected with marriage among the ' local-born' show clearly that there is as yet no notion of hypergamy, and that under pressure of surrounding conditions caste has to be set aside in marriages, and can only be maintained by ignoring the caste of the mothers. There is, however, a strong desire to marry into the same caste, and wherever practicable this is no doubt done. It is probable that caste mainte- nance in its strictness will commence in the isogamy which, in India, is so merged in hypergamy that it was left out of consideration in the last Census Reports. That in time caste will rule marriages and social relations in the Penal Settlement in all its accustomed force, there appears to be little doubt.

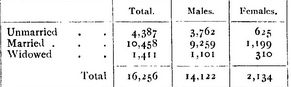

The following table gives statistics of civil conditions in 1901 :

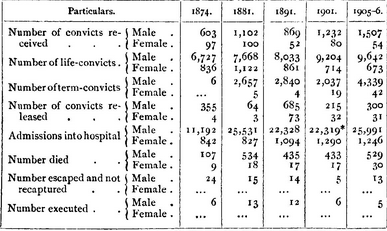

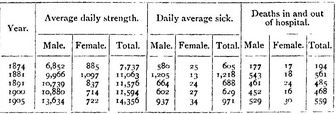

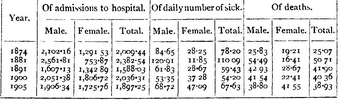

Sickness and mortality are always matters of great consideration among a convict population ; but the conditions are also artificial, owing to the conflict between efficiency in discipline and labour, and the maintenance of a low sick-rate and death-rate by regulations and direct measures. The tendency on one side is to err in the direction of penality and economy, and on the other to secure health by leniency and extravagance. Port Blair has had no exceptional experience of this struggle, which is perpetually maintained wherever prisoners are congregated in civilized countries. All convict sickness and mortality tables must be considered with these qualifications. While the annual rainfall does not bear any real relation to either sickness or death-rate, the monthly rainfall has a decided effect on the sick-rate, which rises regularly every year during the rains (June-September). The following tables compare sickness and mortality in the Settlement for a series of recent years, mostly corresponding with census years :

RATIO PER 1,000 OF AVERAGE STRENGTH

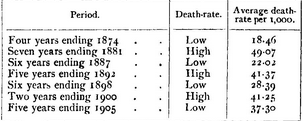

Statistics for isolated years are, however, illusory, as from some causes not yet reported the sickness and mortality appear to rise and fall in successions of years, as shown in the following abstract :

CYCLES OF HEALTH

The worst year on record was 1878-9, with a death-rate of 67-30. Sickness and death-rates for any given period or year are really due to a combination of causes, which are very difficult to determine, but an elaborate inquiry made in 1902 showed that the highest rates are among the latest arrivals. The inference is that the health statistics for any given period depend largely on the number of new arrivals and convicts of short residence present ; and it is possible, for example, that the high rate in 1878-9 was due to the weakness caused by the prevalence of famine in India.

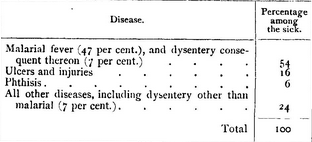

The following figures may be taken as approximately exhibiting the relative importance of prevalent diseases :

Ulcers and injuries are classed together, as they are both ordinarily caused by outdoor work, and are largely due to the carelessness of the convicts. The organization of a mosquito brigade and other apparatus for reducing mosquitoes will perhaps largely reduce the importance of malaria. After fever, dysentery (caused by malaria and otherwise) is the chief disease, and is being combated by improved cooking, milk, and diet. Phthisis (with tuberculosis), as an infectious preventible disease likely to spread if unchecked, is being treated in a special hospital, and by other preventive measures.

Agriculture

Only about 6 per cent, of the labouring convicts are employed as agriculturists, and those chiefly to supply special articles of food for the convicts and staff, such as vegetables, tea, coffee, and cocoa. But agriculture is the main source of livelihood among the ‘self-supporters,' whose labours have contributed to the solid progress of the Settlement. The area of cleared land has increased from 10,421 acres in 1881 to 25,189 in 1905, and that of cultiva- tion from 6,775 to 10,364 acres. Although the working of the regu- lations has very largely reduced the number of ‘ self-supporters ' in the last decade, the result of steady agricultural labour for many years is shown by increased productive capacity in the land, and a rise in the prosperity of the 'self-supporters.' The value of supplies pur- chased from these rose from 1,913 in 1874 to 3,260 in 1881, 3,572 in 1891, and 7,116 in 1901.

Revenue system

All the land in the Penal Settlement is vested in the Crown, and all rights in it are subject to the orders of the Government of India. Prac- tically the land is held at a fixed rent under licence from the Chief Commissioner, on conditions which, system 6 inter alia, subject devolution and transfer to his con- sent, and determine the occupation on compensation of a year's notice or on breach of the conditions. The working of the rules, framed primarily to meet the requirements of the ' self-supporter ' convicts, is in the hands of the District officers, through amins or native revenue officials. Village revenue papers like those maintained in India are kept up, and fixed survey fees are demanded.

House sites, except those of cultivators which are free, are divided into four classes, and a tax is levied varying from Rs. 2 to Rs. 25 according to the net annual income of the holders.

Land for cultivation is divided into valley and hill land, the rent being fixed according to quality with a maximum of Rs. 4-8 per acre for the valley and Rs. 2-4 for the hill land. Licences are given for five years, and may be surrendered on three months' notice. They are subject to special conditions for each holding, and to general con- ditions, among which are that the land may not be surrendered or transferred without permission, and that 5 per cent, of the amount paid by the transferee is paid to the Government as a fine. Similar conditions arc attached to licences for house sites. Grazing fees are levied by licence for the use of the Government (common) lands for grazing or cutting grass for cattle, at the rate of Rs. 2 per annum per animal, and in the case of goats 8 annas per annum each ; but culti- vators may graze two bullocks free for each 5 to 15 blghas (1 2/3 to 5 acres) of land held by them.

‘ Self-supporters,' subject to good behaviour, can hold land on, inter alia, the following general terms : free rations and free use of village servants for six months ; free grant of an axe, hoe, and da ; rent, tax, and cess free for three to four years, with a limit of 5 blghas if the land is uncleared jungle, or for one to two years with a limit of 10 blghas if the land is already cleared. Double holdings are permitted up to two years. 'Self-supporters' must not sublet or alienate their holdings, must occupy them effectively, must assist in making village tanks, roads, and fences, and must keep houses and villages clean and in good repair. Their houses may be sublet, with permission, but only to other ' self-supporters/ as free men and convicts may not live together in villages.

The following cesses and fees are levied : educational cess, collected with the revenue on house sites and land, according to grade, from Rs. 3 to 6 annas per annum ; village conservancy fees, from 4 to 2 annas per house per mensem, collected monthly; chaukldari (vil- lage officials) fees, 4 annas per house or lodger per mensem, collected monthly ; salutri (veterinary) fees, raised from possessors of cattle to provide for veterinary care and inspection of village cattle, at about half the educational cess.

The village officials, who receive fixed salaries, are the chaudhri (headman) and the chauklddr (watchman). The chaudhri is the head of the village, responsible for its peace and discipline, and for assis- tance in the suppression of crime. He is the village tax collector, auctioneer, and assistant land revenue official. The chaukidar is his assistant.

Generally speaking a ‘self-supporter ' has an income of from Rs. 7 a month upwards, and an agricultural ' self-supporter ' can calculate on a net income of not less than Rs. 10 a month. As the peasantry of India go, the ‘self-supporter ' is well off. The free resident popula- tion are probably not in so good circumstances, so far as it depends on the land.

Forests

The forests are worked by officers of the Indian Forest department as nearly as may be on Indian lines, and the Settlement is divided into afforested and unafforested lands. The * reserved ' ^ forest areas amount to about 156 square miles. As little change as possible is made in these, but the growing condition of the Settlement makes it sometimes imperative to effect small altera- tions in area. The Forest department superintends the extraction of timber and firewood, and the construction of tramways ; but the con- version of timber at the steam saw-mill on Chatham Island is done by the Public Works department. In 1904-5 the Forest department employed 1,102 men. Elephants are used to drag logs from the forests to tramways or the sea, and rafts are towed by steamers to Port Blair. This is a comparatively new department for utilizing convict labour, and is now the chief source of revenue in cash. The earnings under this head have increased from 16 lakhs in 1891 and 2.8 lakhs in 1901 to 6.2 lakhs in 1904-5. In the last year the total charges amounted to 3.4 lakhs.

Trade and manufactures

Although the ' self-supporters ' and the free residents follow occupa- tions other than agriculture and Government service, the numbers so employed have but a comparatively small effect on the industries of the Settlement, and practically all the labour available is found by the labouring con- victs. There is an unlimited variety of work, as can be seen from the following list of objects on which they are employed : forestry, land reclamation, cultivation, fishing, cooking, making domestic utensils, breeding and tending animals and poultry, fuel, salt, porterage by land and sea, ship-building, house-building, furniture, joinery, metal-work, carpentry, masonry, stone-work, quarrying, road-making, earthwork, pottery, lime, bricks, sawing, plumbing, glazing, painting, rope-making, basket-work, tanning, spinning, weaving, clothing, driving machinery of many kinds and other superior work, signalling, tide-gauging, designing, carving, metal-hammering, electric-lighting, clerical work and accounting, hospital compounding, statistics, bookbinding, print- ing, domestic and messenger service, scavenging, cleaning, petty super- vision. The machinery is large and important, and some of the works are on a large scale.

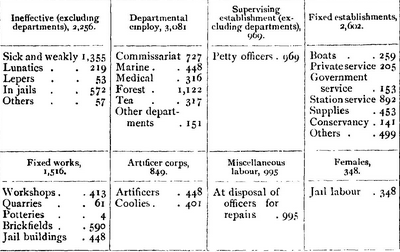

The general heads of employments of labouring convicts appear from the following abstract of the labour statement on December 21, 1906 :

In the Phoenix Bay workshops a great variety of work is performed,

under the heads of supervision, general, machinery, wood, iron, leather,

silver, brass, copper, tin ; and attached to the shops are a foundry,

a tannery, and a limekiln. This department is always growing. The

whole of the out-turn is absorbed locally, and no export trade is under-

taken. The work done has nearly all to be taught to the convicts

employed, and is performed partly by hand and partly by machinery.

By hand they are taught to make cane-work of all sorts, plain and

fancy rope-making, matting, fishing-nets, and wire-netting. They do

painting and lettering of all descriptions. They repair boilers, pumps,

machinery of all sorts, watches and clocks. In iron, copper, and tin,

they learn fitting, tinning, lamp-making, forging, and hammering of all

kinds. In brass and iron they perform casting in large and small sizes,

plain and fancy, and hammering, In wood they turn out all sorts of

carpentry, carriage-building, and carving ; and in leather they make

boots, shoes, harness, and belts. They tan leather and burn lime. By

machinery, in iron and brass, they perform punching, drilling, boring,

shearing, planing, shaping, turning, welding, and screw-cutting. In

wood they learn sawing, planing, tonguing, grooving, moulding, shaping,

and turning; and in wheel-making they do the spoke-tenoning and

mortising. Machinery is continually being added, in order to relieve

labour for forestry and agriculture, the two descriptions of employ-

ment which are best calculated to make the Settlement completely

self-supporting. Machinery will make it industrially, and forestry and

agriculture financially, independent : points that are never lost sight of

and control the labour distribution.

The work of the Marine department about Phoenix Bay is chiefly connected with the building, equipment, and working of the steam- launches, barges, lighters, boats, and buoys maintained.

In the female jail women are employed on the supply of clothing, but they also do everything else necessary for themselves ; and the only two men allowed to work inside the jail are the Hospital Assistant and the jail carpenter.

The bulk of the exports consist of timber, empties belonging to the Commissariat department, canes and other articles of jungle produce, edible birds'-nests, and trepang. The imports consist chiefly of Govern- ment stores’ of various kinds, private provisions, articles of clothing, and luxuries.

Communications

The means of communication are good, and may be grouped as by water about the harbour, by road, and by tram (animal and steam haulage). Eight large and two small steam-launches, and a considerable number of lighters, barges, and boats of all sizes are maintained. Sailing boats, except for the amuse- ment of officers, are, for obvious reasons, not permitted. Several ferries ply at frequent intervals across the harbour. The roads are metalled practically everywhere, and are unusually numerous. Where convicts are concerned, it is a matter of importance to be able to move about quickly at very short notice. The roads include about no miles of metalled and about 50 of unmetalled routes. The tram-lines by animals are chiefly forest, and their situation varies from time to time according to work. The steam tram-lines are from Settlement Brick- fields to South Quarries and Firewood area, 5 miles ; North Bay to North Quarries, 2 miles ; Forest Wimberley Ganj to Shoal Bay, 7 miles ; Bajajagda to Constance Bay and Port Mouat, 6 miles. Short lines are maintained at a number of other places.

The harbour of Port Blair is well supplied with buoys and lights. The lighthouse on Ross Island is visible for 19 miles, and running-in lights, visible 8 miles from both entrances to the harbour, are fixed on the Cellular Jail at Aberdeen and on South Point. There is also a complete system of signalling (semagraph) by day and night on the Morse system, worked by the police. Local posts are frequent, but the foreign mails are irregular. Wireless telegraphy between Port Blair and Diamond Island off the coast of Burma has been worked successfully since 1905, and the various portions of the Settlement are connected by telephone.

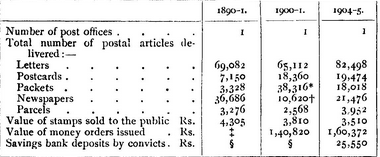

The external postal service is effected by the Port Blair post office, which is under the control of the Postmaster-General, Burma. The Chief Commissioner, however, regulates the relations of the post office with convicts. The following table gives statistics of the postal business :

- Including unregistered newspapers.

t Registered as newspapers in the Post Office. J The figures are included in those given for Bengal. No returns issued.

Finance

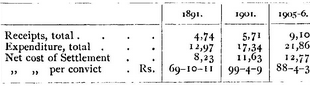

The penal system is primarily one of discipline, financial considera- tions giving way to this all-important point. The labour of the convicts is firstly disciplinary ; secondly, it provides for the wants of the Settlement so far as these can be sup- plied locally ; thirdly, it is expended on objects directly remunerative. All necessary expenditure in cash is granted directly by the Govern- ment of India, and against this are set off the earnings of the convicts in money. The following table gives the total receipts and expendi- ture for a series of years, in thousands of rupees, but a considerable variation occurs from year to year :

The value of convict labour expended on local work and supplies is not included.

The net cash cost of the convict at any given period depends on how far convict labour is employed on objects returning a cash profit, and also on the number of ‘ self-supporters,' who supply local products at a far smaller cost than those procured from places outside the Settle- ment. Since 1891, very large jails and subsidiary buildings have been under construction, absorbing labour which could otherwise have been employed in the forests and on other objects remunerative in cash, while the number of 'self-supporters' has been greatly reduced by a change in the regulations, resulting in a reduction of agricultural holdings and the "amount of jungle cleared annually. Both of these arrangements are disciplinary, and illustrate the dependence of cost on general policy.

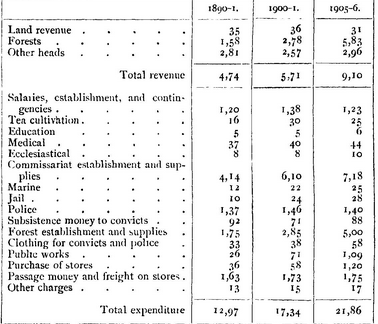

The following table shows the progress of the principal sources of revenue and expenditure, in thousands of rupees :

Public works

The public works are constructed and maintained in all branches by the artificer corps, an institution going back historically long beyond the foundation of Port Blair in the Indian penal settlement system. Men who were artisans before conviction, and men found capable after arrival, are formed into the artificer corps, which is divided into craftsmen, learners, arid coolies. This corps is an organization apart, has special privileges and petty officers of its own, known as foreman petty officers, who labour with their own hands, and also supervise the work of small gangs and teach learners.

The total strength of the British and Native army stationed in the islands in 1905 was 444, of whom 140 were British. The Andaman Islands now belong to the Burma division. The military station, Port Blair, is attached to Rangoon, and is usually garrisoned by British and Native infantry. Port Blair is also the head-quarters of the South Andaman Volunteer Rifles, whose strength is about 30.

The police are organized as a military battalion 701 strong. Their duties are both military and civil, and they are distributed all over the Settlement in stations and guards. They protect the jails, the civil officials, and convict parties working in the jungles, but do not exercise any direct control over the convicts.

Education

The 'local-born' population is better educated than is the rule in India, as elementary education is compulsory for all male children of self-supporters. 7 The sons of the 'local-born' and ot the free settlers are also freely sent to the schools, but not the daughters ; fear of contamination in the latter case being a ruling consideration, in addition to the usual conservatism in such matters. A fair proportion acquire a sufficient knowledge of English for clerkships. Provision is also made for mechanical training to those desiring it, though it is not largely in request, except in tailoring ; and there is a fixed system of physical training for the boys. Native employes of Government use the local schools for the primary education of their children. Six schools are maintained, of which one includes an Anglo-vernacular course, while the others are primary schools. In 1904-5 these contained 152 boys and 2 girls of free parents, and 55 boys and 40 girls of convict parents ; and the total expenditure was Rs. 5,360. Owing to mistakes in enumeration, the census returns for literacy arc of no value.

Medical

There are four district and three jail hospitals in charge of four medical officers, under the supervision of a senior officer of the Indian Medical Service. Medical aid is given free to the whole population, and to Government officials under the usual Indian rules. The convicts unfit for hard labour are classed as sick and detained in hospital, convalescents, light labour invalids, lepers, and lunatics. For each of these classes there are special rules and methods of treatment under direct medical aid. Practically every child born in the Settlement is vaccinated.

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.