Sambalpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Physical aspects

District of the Orissa Division, Bengal, lying between 20 45' and 21 57' N. and 82 38' and 84 26' E., with an area of 3,773 square miles. Up to 1905 the District formed part of the Chhattlsgarh Division of the Central Provinces and on its transfer to Bengal, the Phuljhar zamindari and the Chandarpur- Padampur and Malkhurda estates, with an area of 1,175 square miles and a population (1901) of 189,455 persons were separated from it, and attached to the Raipur and Bilaspur Districts of the Central Provinces. It is bounded on the north by the Gangpur State of Bengal \ on the east by the States of Bamra and Rairakhol ; on the south by Patna, Sonpur, and Rairakhol States ; and on the west by the Raipur and Bilaspur Districts of the Central Provinces. Sambalpur consists of a core of tolerably open country, surrounded on three sides by hills and forests, but continuing on the south into the Feudatory States of Patna and Sonpur and aspects forming the middle basin of the Mahanadi. It is separated from the Chhattlsgarh plain on the west by a range of hills carrying a broad strip of jungle, and running north and south through the Raigarh and Sarangarh States \ and this range marks roughly the boundary between the Chhattlsgarh and Oriya tracts in respect of population and language. Speaking broadly, the plain country con- stitutes the khdlsa^ that is, the area held by village headmen direct from Government, while the wilder tracts on the west, north, and east are in the possession of intermediary pioprietors known locally as zammddrs. But this description cannot be accepted as entirely accurate, as some of the zammdari estates lie in the open plain, while the khdlsa area includes to the north the wild mass of hills known as the Barapahar.

The Mahanadi river traverses Sambalpur from north to south-east for a distance of nearly 90 miles. Its width extends to a mile or more in flood-time, and its bed is rocky and broken by rapids over portions of its course. The principal tributary is the Ib, which enters the District from the Gangpur State, and flowing south and west joins the Mahanadi about 12 miles above Sambalpur. The Kelo, another tributary, passes Raigarh and enters the Mahanadi near Padampur. The Ong rises in Khariar and passing through Borasambar flows into the Mahanadi near Sonpur. Other tributary streams are the Jira, Borai, and Mand. The Barapahar hills form a compact block 1 6 miles square in the north-west of the District, and throw out a spur to the south-west for a distance of 30 miles, crossed by the Raipur- Sambalpur road at the Singhora pass. Their highest point is Debrlgarh, at an altitude of 2,276 feet. Another range of importance is that of Jharghati, which is crossed by the railway at Rengali station. To the southward, and running parallel with the Mahanadi, a succession of broken chains extends for some 30 miles. The range, however, attains its greatest altitude of about 3,000 feet in the Borasambar zammdari in the south-west, where the Narsinghnath plateau is situated. Isolated peaks rising abruptly from the plain are also frequent; but the flat- topped trap hills, so common a feature in most Districts to the north and west, are absent. The elevation of the plains falls from nearly 750 feet in the north to 497 at Sambalpur town. The surface of the open country is undulating, and is intersected in every direction by drainage channels leading from the hills to the Mahanadi. A con- siderable portion of the area consists of ground which is too broken by ravines to be banked up into rice-fields, or of broad sandy ridges which are agriculturally of very little value. The configuration of the country is exceedingly well adapted for tank-making, and the number of village tanks is one of the most prominent local features.

The Barapahar hills belong to the Lower Vindhyan sandstone forma- tion, which covers so large an area in Raipur and Bilaspur. Shales, sandstones, and limestones are the prevalent rocks. In the Barapahar group coal-bearing sandstones are found. The rest of the District is mainly occupied by metamorphic or crystalline rocks. Laterite is found more or less abundantly resting upon the older formations in all parts of the area.

Blocks of 'reserved' forest clothe the Barapahar hills in the north and the other ranges to the east and south-east, while many of the zammdari estates are also covered with jungle over the greater part of their area. The forest vegetation of Sambalpur is included in the great sal belt. Other important trees are the beautiful Anogeissus acuminata } saj ( Terminalia tomentosa), bljasdl (Pterocarpus Marsupium}) and shisJiam (Dalbergia Sissoo). The light sandy soil is admirably fitted for the growth of trees, and the abundance of mango groves and clumps of palms gives the village scenery a distinct charm. The semul or cotton-tree (Bonibax malabaricuni) is also common in the open country.

The usual wild animals occur. Buffaloes, though rare, are found in the denser forests of the west, and bison on several of the hill ranges. Sambar are fairly plentiful, Chttal or spotted deer, mouse deer, ' ravine deer' (gazelle), and the four- horned antelope are also found. Tigers were formerly numerous, but their numbers have greatly decreased in recent years. Leopards are common, especially in the low hills close to villages. The comparatively rare brown flying squirrel (Pteromys oral) is found in Sambalpur. It is a large squirrel with loose folds of skin which can be spread out like a small parachute. Duck and teal are plentiful on the tanks in the cold season, and snipe in the stretches of irrigated rice-fields below the tanks. Flocks of demoiselle cranes frequent the sandy stretches of the Mahanadi at this time. Fish of many kinds, including mahseer, abound in the Mahanadi and other rivers. Poisonous snakes are very common.

The climate of Sambalpur is moist and unhealthy. The ordinary temperature is not excessive, but the heat is aggravated at Sambalpur town during the summer months by radiation from the sandy bed of the Mahanadi. During breaks in the rains the weather at once becomes hot and oppressive, and though the cold season is pleasant it is of short duration. Malarial fever of a virulent type prevails in the autumn months, and diseases of the spleen are common in the forest tracts.

The annual rainfall at Sambalpur town averages 59 inches \ that of Bargarh is much lighter, being only 49 inches. Taking the District as a whole, the monsoon is generally regular. Sambalpur is in the track of cyclonic storms from the Bay of Bengal, and this may possibly be assigned as the reason.

History

The earliest authentic records show Sambalpur as one of a cluster of States held by Chauhan Rajputs, who are supposed to have come from Mainpurl in the United Provinces. In 1797 the District was conquered and annexed by the Marathas; but owing to British influence the Raja was restored in 1817, and placed under the political control of the Bengal Govern- ment. On the death of a successor without heirs in 1849 the District was annexed as an escheat, and was administered by the Bengal Government till 1862, when it was transferred to the Central Provinces. During the Mutiny and the five years which followed it, the condition of Sambalpur was exceedingly unsatisfactory, owing to disturbances led by Surendra Sah, a pretender to the State, who had been imprisoned in the Ranch! jail for murder, but was set free by the mutineers. He returned to Sambalpur and instigated a revolt against the British Government, wt ich he prosecuted by harassing the people with dacoities. He was joined by many of the zamindars^ and it is not too much to say that for five years the District was in a state of anarchy. Surendra Sah was deported in 1864 and tranquillity restored.

The archaeological remains are not very important. There are temples at Barpali, Gaisama 25 miles south-west of Sambalpur, Padam- pur in Borasarnbar, Garh-Phuljhar, and Sason, which are ascribed to ancestors of the Sambalpur dynasty and of the respective zammddrs. The Narsinghnath plateau in the south of the Borasambar zamlndari is locally celebrated for its temple and the waterfall called Sahasra Dhara or ' thousand streams,' which is extremely picturesque. Huma on the Mahanadl, 15 miles below Sambalpur town, is another place of pilgrimage. It is situated at the junction of a small stream, called the Jholjir, with the Mahanadl, and contains a well-known temple of Mahadeo.

Population

The population of the District at the three enumerations was as follows: (1881) 693,499, (1891) 796,413, and (1901) 829,698. On the transfer of territory in 1905 the population was reduced to 640,243 persons. Between 1881 and 1891 the increase was nearly 15 per cent., the greater part of which occurred in the zaminddris, and must be attributed to greater efficiency of enumeration. The District had a half crop in 1897 and there was practically no distress; but in 1900 it was severely affected, and the mortality was augmented by a large influx of starving wanderers from native territory. The District furnishes coolies for Assam, and it is estimated that nearly 12,000 persons emigrated during the decade. There is only one town, SAMBALPUR, and 1,938 inhabited villages.

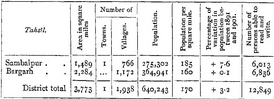

The principal statistics of population, based on the Census of 1901, are given below ;

The figures for religion show that nearly 583,000 persons, or 91 per cent of the population, are Hindus, and 54,000, or 8 per cent., Animists. Muhammadans number only about 3,000. Oriya is the vernacular of 89 per cent of the population, A number of tribal dialects are also found, the principal being Oraon with nearly 25,000 speakers, Kol with n,ooo, and Kharia with 5,000.

The principal castes are Gonds (constituting 8 per cent, of the popu- lation), Koltas (n per cent,), Savaras (9 per cent.), Gahras or Ahlrs (n per cent.), and Gandas (13 per cent.). Of the sixteen zamlndari estates, ten are held by Raj Gonds; two, Rajpur and Barpali, by Chauhan Rajputs ; one, Rampur, by another Rajput ; two, Borasambar and Ghens, by Binjhals; and one, Bijepur, by a Kolta. The Gond families are ancient ; and their numbers seem to indicate that previous to the Oriya immigration they held possession of the country, subduing the Munda tribes who were probably there before them. A trace of the older domination of these is to be found in the fact that the Binjhal zamlndar of Borasambar still affixes the ttka to the Maharaja of Patna on his accession. Koltas are the great cultivating caste, and have the usual characteristics of frugality, industry, hunger for land, and readiness to resort to any degree of litigation rather than relinquish a supposed right to it. They strongly appreciate the advantages of irrigation, and show considerable public spirit in constructing tanks which will benefit the lands of their tenants as well as their own.

The Savaras or Saonrs of Sambalpur, though a Dravidian tribe, live principally in the open country and have adopted Hindu usages. They are considered the best farm-servants and are very laborious, but rarely acquire any property. Brahmans (28,000), though not very numerous, are distinctly the leading caste in the District. The Binjhals (39,000) are probably Hinduized Baigas, and live principally in the forest tracts. Kewats (38,000), or boatmen and fishermen, are a numer- ous caste. The Gandas (105,000), a Dravidian tribe now performing the menial duties of the village or engaging in cotton-weaving, have strong- criminal propensities which have recently called for special measures of repression. About 78 per cent, of the population of the District are returned as dependent on agriculture. A noticeable feature of the rural life of Sambalpur is that i\\QJhankar, or village priest, is a universal and recognized village servant of fairly high status. He is nearly always a member of one of the Dravidian tribes, and his business is to conduct the worship of the local deities of the soil, crops, forests, and hills. He generally has a substantial holding, rent free, containing some of the best land in the village. It is said locally that \hzjhankar is looked on as the founder of the village, and the representative of the old owners who were ousted by the Hindus. He worships on their behalf the indigenous deities, with whom he naturally possesses a more intimate acquaintance than the later immigrants; while the gods of these latter cannot be relied on to exercise a sufficient control over the works of nature in the foreign land to which they have been imported, or to ensure that the earth and the seasons will regularly perform their necessary functions in producing sustenance for mankind.

Christians number 722, including 575 natives, of whom the majority are Lutherans and Baptists. A station of the Baptist Mission is main- tained at Sambalpur town.

Agriculture

The black soil which forms so marked a feature in the adjoining Central Provinces is almost unknown in Sambalpur. It occurs in the north-west of the District, beyond the cross range of Vindhyan sandstone which shuts off the Ambabhona pargana^ and across the Mahanadi towards the Bilaspur border. The soil which covers the greater part of the country is apparently derived from underlying crystalline rocks, and the differ- ences found in it are due mainly to the elimination and trans- portation effected by surface drainage. The finer particles have been carried into the low-lying areas along drainage lines, rendering the soil there of a clayey texture, and leaving the uplands light and sandy. The land round Sambalpur town, and a strip running along the north bank of the Mahanad! to the confines of Bilaspur District, is the most productive, being fairly level, while the country over the greater part of the Bargarh tahsil has a very decided slope, and is much cut up by ravines and watercourses. Nearly all the rice is sown broadcast, only about 4 per cent, of the total area being transplanted. For thinning the crop and taking out weeds, the fields are ploughed up when the young plants are a few inches high, as in Chhattisgarh. A considerable proportion of the area under culti- vation, consisting of high land which grows crops other than rice, is annually left fallow, as the soil is so poor that it requires periodical rests.

1 No less than 235 square miles are held revenue free or on low quit- rents, these grants being either for the maintenance of temples or gifts to Brahmans, or assignments for the support of relatives of the late ruling family. The zamlnddn estates cover 48 per cent, of the total area of the District, 109 acres are held ryotwdri^ and the balance on the tenures described below (p. 15). In 1903-4, 396 square miles, or 9 per cent, of the total area, were included in Government forests; 290 square miles, or 7 per cent., were classed as not available for culti- vation; and 1,102 square miles, or 26 per cent, as cultivable waste other than fallow. The remaining area, amounting to about 2,443 square miles, or nearly 64 .per cent, of that of the District, excluding Govern- ment forests, was occupied for cultivation. In the more level parts of the open country cultivation is close, but elsewhere there seems to be still some room for expansion. Rice is the staple crop of Sambalpur, covering 1,355 square miles in 1903-4. Other crops are

1 The figures in this paragraph refer to the area of the District as it stood before the transfer of Phuljhar, Chandarpur, and Malkhurda, revised statistics of cultivation not being available. til or sesamum (158 square miles), the pulse urad (145), anil (94). Nearly 12,000 acres are under cotton and 4,400 cane. The pulses are raised on the inferior high-lying land manure, the out-turn in consequence being usually very bmall. The pulse kitlthl (Dolichos umflorus] covers 56 square miles. Cotton and /// are also grown on this inferior land. Sugar-cane was formerly a crop of some importance ; but its cultivation has decreased in recent years, owing to the local product being unable to compete in price with that imported from Northern India.

The harvests have usually been favourable in recent years, and the cropped area steadily expanded up to 1899, when the famine of 1900 caused a temporary decline. New tanks have also been constructed for irrigation, and manure is now utilized to a larger extent. During the decade ending 1904, a total of Rs. 77,000 was advanced under the Land Improvement Loans Act, and Rs. 68,000 under the Agricul- turists' Loans Act.

In 1903-4 the irrigated area was only 31 square miles, but in the previous year it had been over 196, being the maximum recorded. With the exception of 12 square miles under sugar-cane and garden produce, the only crop irrigated is rice. The suitability of the District for tank-making has already been mentioned, and it is not too much to say that the very existence of villages over a large portion of the area is dependent on the tanks which have been constructed near them. There are 9,500 irrigation tanks, or between three and four to every village in the District on an average. The ordinary Sambalpur tank is constructed by throwing a strong embankment across a drainage line, so as to hold up an irregularly shaped sheet of water. Below the embankment a four-sided tank is excavated, which constitutes the drinking supply of the village. Irrigation is generally effected by leading channels from the ends of the embankment, but in years of short rainfall the centre of the tank is sometimes cut through. Embankments of small size are frequently thrown across drainage channels by tenants for the benefit of their individual holdings. The Jambor and Sarsutia nullahs near Machida are perennial streams, and the water is diverted from them by temporary dams and carried into the fields. In certain tracts near the MahanadT, where water is very close to the surface, temporary wells are also sometimes constructed for the irri- gation of rice. Irrigation from permanent wells is insignificant. Several projects for new tanks have been prepared by the Irrigation department.

The cattle of the District are miserably poor, and no care is exercised in breeding. As the soil is light and sandy, however, strong cattle are not so requisite here as elsewhere. For draught purposes larger animals are imported from Berar, Buffaloes are largely used for cultivation. They are not as a rule bred locally, but imported from the northern

VOL. XXII. D

Districts through Bila.vpur and Surguja. Those reared in the District are distinctly infeiior. Buffaloes are frequently also used for draught, and for pressing oil and sugar-cane. Only a few small ponies are bred in the District for riding. Goats and sheep are kept by the lower castes for food only. Their manure is also sometimes used, but does not command a price. There are no professional shepherds, and no use is made of the wool of sheep.

Forests

The area of 'reserved' forest is 396 square miles. It is situated on the Barapahar hills in the north of the Bargarh taksll, and on the ranges in the west and south-west of the Sambalpur tahsil. There are two types of forest, the first con- sisting of the sal tree interspersed with bamboos and other trees, and the second or mixed forest of bamboos and inferior species. Sal forest occupies all the hills and valleys of the Sambalpur range, and the prin- cipal valleys of the Barapahar range, or an area of about 238 square miles, It thrives best on well-drained slopes of sandy loam. The mixed forest is situated on the rocky dry hills of the Barapahar range, where sal will not grow, and covers 155 square miles. The revenue in 1903-4 was Rs. 34,000, of which about Rs. 12,000 was realized from the sale of bamboos, Rs. 10,000 from timber, Rs. 3,600 from grazing dues, and Rs. 5,000 from firewood.

Minerals

The Rampur coal-field is situated within the District. Recent exploration has resulted in the discovery of one seam of good steam

Minerals C al and two of rather inferior quality within easy reach of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway. The former, known as the Ib Bridge seam, contains coal more than 7 feet in thick- ness. Two samples which have been analysed yielded 52 and 55 per cent, respectively of fixed carbon. Iron ores occur in most of the hilly country on the borders of the District, particularly in the Borasambar, Phuljhar 1 , Kolabira, and Rampur zamlndaris. Some of them are of good quality, but they are worked by indigenous methods only. There are 160 native furnaces, which produce about 1,120 cwt. of iron annually. When Sambalpur was under native rule diamonds were obtained in the island of Hirakud (* diamond island ') in the Mahanadl. The Jharias or diamond-seekers were rewarded with grants of land in exchange for the stones found by them. The right to exploit the diamonds, which are of very poor quality, was leased by the British Government for Rs. 200, but the lessee subsequently relinquished it. Gold in minute quantities is obtaine&d by sand-washing in the Ib river. Lead ores have been found in Talpatia, Jhunan, and Padampur 2 , and antimony in Junani opposite Hirakud. Mica exists, but the plates are too small to be of any commercial value.

1 Now in Raipur District, Cential Piuvince-. " Now in Bilaspui District, Central Provinces. -

Trade and communication

Tasar silk-weaving is an important industry in Sambalpur. The cocoons are at present not cultivated locally, but are imported from Chota Nagpur and the adjoining States. Plain and drilled cloth is woven. Remenda, Barpali, Chan- darpur 1 , and Sambalpur are the principal centres. A little cloth is sent to Ganjam, but the greater part is sold locally. Cloths of cotton with silk borders, or intermixed with silk, are also largely woven. Bhuhas and Koshtas are the castes engaged, the former weaving only the prepared thread, but the latter also spinning it. Cotton cloth of a coarse texture, but of considerable taste in colour and variety of pattern, is also woven in large quantities, imported thread being used almost exclusively. It is generally worn by people of the District in preference to mill-woven cloth. A large bell-metal industry exists at Tukra near Kadobahal, and a number of artisans are also found at Remenda, Barpah, and Bijepur. Brass cooking and water pots are usually imported from Onssa. The iron obtained locally is used for the manufacture of all agricultural implements except cart-wheel tires. Smaller industries include the manufacture of metal beads, saddles, and drums.

Rice is the staple export of Sambalpur, being sent principally to Calcutta, but also to Bombay and Berar. Other exports include oil- seeds, sleepers, dried meat, and san-hemp. Salt comes principally from Ganjam, and is now brought by rail instead of river as formerly. Sugar is obtained from Mirzapur and the Mauritius, and gur or unrefined sugar from Bengal. Kerosene oil is brought from Calcutta, and cotton cloth and yarn from Calcutta and the Nagpur mills. Silk is imported from Berhampur. Wheat, gram, and the pulse arhar are also imported,, as they are not grown locally in sufficient quantities to meet the demand. The weekly markets at Sambalpur and Bargarh aie the most important in the District. Bhukta, near Ambabhona, is the largest cattle fair and after it rank those of Bargarh, Saraipah, and Talpatia. Jamurla is a large mart for oilseeds ; Dhama is a timber market ; and Bhlkhampur and Talpatia are centres for the sale of country iron implements. A certain amount of trade in grain and household utensils is transacted at the annual fairs of Narsinghnath and Huma.

The main line of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway passes for a short

distance through the north-east of the District, with a length of nearly

30 miles and three stations. From Jharsugra junction a branch line

runs to Sambalpur town, 30 miles distant, with three intervening

stations. The most important trade route is the Raipur-Sambalpur

road, which passes through the centre of the Bargarh tahsil. Next

to this come the Cuttack road down to Sonpur, and the Sambalpm-

1 Now in Bilaspur District, Ce.:tial Provinces. Bilaspur road. None of these is metalled throughout, but the Raipur- Sambalpur road is embanked and gravelled. The District has 27 miles of metalled and 185 of unmetalled roads, and the expenditure on main- tenance is Rs. 24,000. The Public Works department is in charge of 115 miles and the District council of 97 miles of road. There are avenues on 68 miles. The Mahanadi river was formerly the great outlet for the District trade. Boat transport is still carried on as far as Sonpur, but since the opening of the railway trade with Cuttack by this route has almost entirely ceased. Boats can ascend the Mahanadi as far as Arang in Raipur, but this route is also little used owing to the dangerous character of the navigation.

Famine

Sambalpur is recorded as having suffered from partial failures of crops in 1834, 1845, ^74, and 1877-8, but there was nothing more than slight distress in any of those years. In 1896 the mi ' rice crop failed over a small part of the District, prin- cipally in the Chandarpur zammddri t and some relief was administered here. The numbers, however, never rose to 3,000, while in the rest of the District agriculturists made large profits from the high prices prevailing for rice. The year 1900 was the first in which there is any record of serious famine. Owing to the short rainfall in 1899, a com- plete failure of the rice crop occurred over large tracts of the District, principally in the north and west. Relief operations extended over a whole year, the highest number relieved being 93,000 in August, 1900, or 12 per cent, of the population; and the total expenditure was 8 lakhs.

Administration

The Deputy-Commissioner has a staff of three Assistant or Deputy- Collectors, and a Sub-Deputy-Collector. For administrative purposes the District is divided into two tahsils. Sambalpur and Bargarh, each having a tahsildar and Bargarh

also a naib-tahsildar* The Forest officer is generally a member of the Provincial service.

The civil judicial staff consists of a District and two Subordinate Judges and a Munsif at each tahsiL Sambalpur is included in the Sessions Division of Cuttack. The civil litigation has greatly increased in recent years, and is now very heavy. Transactions attempting to evade the restrictions of the Central Provinces Tenancy Act on the transfer of immovable property are a common feature of litigation, as also are easement suits for water. The crime of the District is not usually heavy, but the recent famine produced an organized outbreak of dacoity and house-breaking.

Under native rule the village headmen, or gaontids^ were responsible for the payment of a lump sum assessed on the village for a period of years, according to a lease which was periodically revised and re- newed. The amount of the assessment was recovered from the cultivators, and the headmen were remunerated by holding part of the village area free of revenue. The headmen were occasionally ejected for default in the payment of revenue, and the grant of a new lease was often made an opportunity for imposing a fine which the gaontia paid in great part from his own profits, and did not recover from the cultivators. The cultivators were seldom ejected except for default in the payment of revenue, but they rendered to their gaontias a variety of miscellaneous services known as Ihetl bigari. Taxation under native rule appears to have been light. When the District escheated to the British Government, the total land revenue of the khaha area was about a lakh of rupees, nearly a quarter of which was alienated. Short-term settlements were made in the years succeeding the annexation, till on the transfer of the District to the Central Pro- vinces in 1862 a proclamation was issued stating that a regular long-term settlement would be made, at which the gaontias or hereditary managers and rent-collectors of villages would receive proprietary rights. The protracted disturbances caused by the adherents of Surendra Sah, how- ever, prevented any real progress being made with the survey ; and this gave time for the expression of an opinion by the local officers that the system of settlement followed in other Districts was not suited to the circumstances of Sambalpur. After considerable discussion, the inci- dents of land tenures were considerably modified in 1872.

'Went gaontias or hereditary managers received proprietary rights only in their bhogrd or home-farm land, which was granted to them free of revenue in lieu of any share or drawback on the rental paid by tenants. Waste lands and forests remained the property of Government; but the gaontias enjoy the rental on lands newly broken up during the currency of settlement. A sufficiency of forest land to meet the necessities of the villagers was allotted for their use, and in cases where the area was in excess of this it was demarcated and set apart as a fuel and fodder reserve. Occupancy right was conferred on all tenants except sub-tenants vibhogra.

The system was intended to restrict the power of alienation of land, the grant of which had led to the expropriation of the agricultural by the money-lending castes, and the same policy has recently received expression in the Central Provinces Tenancy Act of 1898. A settlement was made for twelve years in 1876, by which the revenue demand was raised to 1-16 lakhs, the net revenue, exclud- ing assignments, being Rs. 93,000. On the expiry of this settlement, the District was again settled between 1885 and 1889, and the assess- ment was raised to 1-59 lakhs, or by 38 per cent. The revenue incidence per acre was still extremely low, falling at only R. 0-3-11 (maximum R. o-8-io, minimum R. 0-2) excluding the zammdaris. The term of this settlement varied fiom fourteen to fifteen years. It expired in 1902 and the District is again under settlement. The collections of land revenue and total revenue have varied as shown below, in thousands of rupees :

The management of local affairs, outside the municipal area of SAMBALPUR TOWN, is entrusted to a District council and four local boards, one each for the northern and southern zamindari estates, and one for the remaining area of each tahsil The income of the District council in 1903-4 was Rs. 55,000, while the expenditure on education was Rs. 24,000.

The police force consists of 492 officers and men, including a special reserve of 25, and 3 mounted constables, besides 2,765 watchmen for 2,692 inhabited towns and villages. The District Superintendent sometimes has an Assistant. Special measures have recently been taken to improve the efficiency of the" police force, by the importation of subordinate officers from other Districts. Sambalpur has a District jail with accommodation for 187 prisoners, including 24 females. The daily average number of prisoners in 1904 was 141.

In respect of education the District is very backward. Only 3-3 per cent, of the male population were able to read and write in 1901, and but 400 females were returned as literate. The proportion of children under instruction to those of school-going age is 6 per cent. Statistics of the number of pupils under instruction are as follows: (1880-1) 3,266, (1890-1) 7,145, (1900-1) 4,244, (1903-4) 9,376. The last figure includes 2,366 girls, a noticeable increase having lately been made. The educational institutions comprise a high school at Sambalpur town, an English middle school, 6 vernacular middle schools, and 120 primary schools. Primary classes and masters are attached to two of the middle schools. There are six Government girls' schools in the District, A small school for the depressed tribes has been opened by missionaries. Oriya is taught in all the schools. The District is now making progress in respect of education, a number of new schools having been opened recently. The total expenditure in 1903-4 was Rs. 40,000, of which Rs. 35,000 was provided from Provincial and Local funds and Rs. 4,700 by fees.

The District has seven dispensaries, with accommodation for 62 in- patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 85,840, of whom 836 were in-patients, and 1,999 operations were performed. The total expendituie was Rs. 10,700.

Vaccination is compulsory in the municipal town of Sambalpur. The number of persons successfully vaccinated in 1903-4 was 45 per 1,000 of the District population. [J. B. Fuller, Settlement Report (1891). A District Gazetteer is being compiled.]