Shahpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Shahpur District

District in the Rawalpindi Division of the Punjab, lying between 31 32' and 32 42' N. and 71 37' and 73 23' E., with an area of 4,840 square miles. It adjoins the Districts of Attock and Jhelum on the north, Gujrat on the east, Gujranwala on the south-east, Jhang on the south, and Mianwali on the west.

Physical aspects

The Jhelum river divides Shahpur into two parts, nearly equal in area. Entering the District at its north-east corner, the river flows almost due west for 60 miles, and then near Khushab turns southward, its width increasing from -sDects 2 to 15 miles during its course through the District. The tendency of the river to move westward has caused it to cut in under its right bank, receding from the eastern bank, under which deposits of silt have formed a fertile stretch of low-lying land densely populated by prosperous cultivators. The Jhelum valley, though it comprises at most a fourth of the area of the whole District, contains more than a half of its population and all its towns.

East of the Jhelum, the District includes that part of the Chaj Doab, or country between the Chenab and Jhelum, which is called the Bar, consisting of a level uncultivated upland covered with brushwood. Its climate is dry and healthy. The character of this tract is, however, being rapidly changed by the Jhelum Canal. As the network of irrigation spreads, trees and bushes are cut down, and the country cleared for cultivation. Metalled roads are being built, and colonists imported from the congested Districts of the Province, while the Jech Doab branch of the North-Western Railway has been extended to Sargodha, the head-quarters of the new Jhelum Colony.

West of the Jhelum stretches an undulating waste of sandhills knovsn as the Thai, extending to the border of Mianwali. Broken only by an occasional well, and stretching on three sides to the horizon, the Thai from Nurpur offers a dreary spectacle of rolling sandhills and stunted bushes, relieved only by the Salt Range which rises to the north. Good rain will produce a plentiful crop of grass, but a failure of the rains, which is more usual, means starvation for men and cattle. North of the Thai runs the Salt Range. Rising abruptly from the plains, these hills run east and west, turning sharply to the north into Jhelum District at one end and Mianwali at the other* The general height of the range is 2,500 feet, rising frequently to over 3,000 feet and culminating in the little hill station of Sakesar (5,010 feet). The mirage is very common where the Salt Range drops into the Thai.

1 Thiotighout this article the information given relates to the District as it was before the fan-nation of the Sargodha takstl in 1906. Brief notices of the new talisil and its head- quartets will bj found m the articles on SARGODHA TAHSIL and SAR- GOUHA TOWN.

The greater part of the District lies on the alluvium, but the central portion of the Salt Range, lying to the north of the Jhelum river, is of interest. The chief feature of this portion of the range is the great development attained by the Productus limestone, with its wealth of Permian fossils. It is overlain by the Triassic ceratite beds, which are also highly fossiliferous. Here, too, upper mesozoic beds first begin to appear ; they consist of a series of variegated sandstones with Jurassic fossils, and are unconformably overlain by Nummulitic limestone and other Tertiary beds. The lower part of the palaeozoic group is less extensively developed than in the eastern part of the range, but the salt marlj with its accompanying rock-salt, is still a constant feature in most sections. Salt of great purity is excavated at the village of Warcha 1 .

East of the Jhelum the flora is that of the Western Punjab, with an admixture of Oriental and desert species ; but recent canal extensions tend to destroy some of the characteristic forms, notably the saltworts (species of Hakxylon^ Salicornia^ and Sahola\ which in the south- east of the District often constitute almost the sole vegetation. The Thai steppe, west of the Jhelum, is a prolongation northwards of the Indian desert, and its flora is very similar to that of Western Rajputana. In the Salt Range a good many Himalayan species are found, but the general aspect of the flora is Oriental. The box (B?txus) t a wild olive, species of Ztzyphus, Sageretta, and Dodonaea are associated with a number of herbaceous plants belonging to genera well-known in the Levant as well as in the arid North- Western Himalaya, e.g. Dianthus^ Scorzonera, and Merendera. At higher levels Himalayan forms also appear. Trees are unknown in the Thai, and, except Acacia modesta and Tecoma undufata, are usually planted; but the klkar (Acacia arabica) is naturalized on a large scale on the east bank of the Jhelum.

'Ravine deer' (Indian gazelle) are found in the Salt Range, the Thai, and the Bar. There are antelope in very small numbers in the Shahpur tahsl^ while hog are found in the south-east of the District and occasionally in the Salt Range. In the Salt Range leopards are rare and wolves common. Urial (a kind of moufflon) also live on the hills, and jackals are numerous everywhere.

The town of Khushab and the waterless tracts of the Bar and Thai are, in May and June, among the hottest parts of India. The thermo- meter rises day after day to 115 or more, and the average daily maximum for June is 108. When the monsoon has once begun, the temperature rarely rises above 105. The Salt Range valleys are

1 Wynne, 'Geology of the Salt Range,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxiv j C. S. Middlemiss, Geology of the Salt Range,' Records, Geological Survey of India, vol. xiv, pt. i. generally about 10 cooler than the plains, while at Sakesar the temperature seldom ranges above 90 or below 70 in the hot months, January is the coldest month. The average minimum at Khushab is 39. The District is comparatively healthy, though it suffers con- siderably from fever in the autumn months. The Bar has a better climate than the river valleys, but has deteriorated since the opening of the Jhelum Canal.

The rainfall decreases rapidly as one goes south-west, away from the Himalayas. In the Jhelum valley and Salt Range it averages 15 inches. In the Thai the average is 7 inches. The great flood of 1893 will be long remembered. On July 20-1 in that year the Chenab dis- charged 700,000 cubic feet per second, compared with an average discharge of 127,000.

History

At the time of Alexander's invasion, the Salt Range between the Indus and the Jhelum was ruled by Sophytes, who submitted without resistance to Hephaestion and Craterus in the autumn of 326 B.C. The capital of his kingdom is possibly to be found at Old BHERA. After Alexander left India, the country comprised in the present District passed successively, with intervals of comparative independence, under the sway of Mauryan, Bactrian, Parthian, and Kushan kings, and was included within the limits of the Hindu kingdom of Ohind or Kabul. In the seventh and eighth centuries, the Salt Range chieftain was a tributary of Kashmir. Bhera was sacked by Mahmud of Ghazni, and again two centuries later by the generals of Chingiz Khan. In 1519 Babar held it to ransom; and in 1540 Sher Shah founded a new town, which under Akbar became the head-quarters of one of the subdivisions of the Sitbah of Lahore, In the reign of Muhammad Shah, Raja Salamat Rai, a Rajput of the Anand tribe, administered Bhera and the surrounding country; while Khushab was managed by Nawab Ahmadyar Khan, and the south-eastern tract along the Chenab formed part of the territories under the charge of Maharaja Kaura Mai, governor of Multan. At the same time, the Thai was included among the dominions of the Saloch families of Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan.

During the anarchic period which succeeded the disruption of the Mughal empire, this remote region became the scene of Sikh and Afghan incursions. In 1757 a force under Nur-ud-din Bamizai, dis- patched by Ahmad Shah Durrani to assist his son Timur Shah in repelling the Marathas, crossed the Jhelum at Khushab, marched up the left bank of the river, and laid waste the three largest towns of the District Bhera and Miani rose again from their ruins, but only the foundations of Chak Sanu now mark its former site. About the same time, by the death of Nawab Ahmadyar Khan, Khushab also passed into the hands of Raja Salamat Rai. Shortly afterwards Abbas Khan, a Khattak, who held Pind Dadan Khan and the Salt Range for Ahmad Shah, treacherously put the Raja to death, and seized Bhera, But Abbas Khan was himself thrown into prison as a revenue defaulter; and Fateh Singh, nephew of Salamat Rai, then recovered his uncle's dominions.

After the final success of the Sikhs against Ahmad Shah in 1763, Chattar Singh, of the Sukarchakia mis I or confederacy, overran the whole Salt Range, while the Bhangi chieftains parcelled out among themselves the country between those hills and the Chenab. Mean- while, the Muhammadan rulers of Sahiwal, Mitha Tiwana, and Khushab had assumed independence, and managed, though hard pressed, to resist the encroachments of the Sikhs. The succeeding period was one of constant anarchy, checked only by the gradual rise of Mahan Singh, and his son, the great Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The former made himself master of Miani in 1783, and the latter succeeded in annexing Bhera in 1803. Six years later, Ranjit Singh turned his arms against the Baloch chieftains of Sahiwal and Khushab, whom he over- came by combined force and treachery. At the same time he swallowed up certain smaller domains in the same neighbourhood; and in 1810 he effected the conquest of all the country subject to the Sial chiefs of Jhang. In 1816 the conqueror turned his attention to the Maliks of Mitha Tiwana. The Muhammadan chief retired to Nurpur, in the heart of the Thai, hoping that scarcity of water and supplies might check the Sikh advance. But Ranjit Singh's general sank wells as he marched, so that the Thvanas fled in despair, and wandered about for a time as outcasts. The Maharaja, however, after annexing their territory, dreaded their influence and invited them to Lahore, where he made a liberal provision for their support. On the death of the famous Hari Singh, to whom the Tiwana estates had been assigned, Fateh Khan, the representative of the Tiwana family, obtained a grant of the ancestral domains. Thenceforward, Malik Fateh Khan took a prominent part in the turbulent politics of the Sikh realm, after the rapidly succeeding deaths of Ranjit Singh, his son, and grandson. Thrown into prison by the opposite faction, he was released by Lieutenant (afterwards Sir Herbert) Edwardes, who sent him to Bannu on the outbreak of the Multan rebellion to relieve Lieutenant Reynell Taylor. Shortly afterwards the Sikh troops mutinied, and Fateh Khan was shot down while boldly challenging the bravest champion of the Sikhs to meet him in single combat. His son and a cousin proved themselves actively loyal during the revolt, and were rewarded for their good service both at this period and after the Mutiny of 1857.

Shahpur District passed under direct British rule, with the rest of the Punjab, at the clobe of the second Sikh War. At that time the greater part of the country was peopled only by wild pastoral tribes, without fixed abodes. Under the influence of settled government, they began to establish themselves in permanent habitations, to cultivate the soil in all suitable places, and to acquire a feeling of attachment to their regular homes. The Mutiny of 1857 had little influence upon Shah- pur, The District remained tranquil ; and though the villages of the Bar gave cause for alarm, no outbreak of sepoys took place, and the wild tribes of the upland did not revolt even when their brethren in the neighbouring Multan Division took up arms. A body of Tiwana horse, levied in this District, did excellent service during the Mutiny, and was afterwards incorporated in the regiment now known as the 1 8th (Tiwana) Lancers.

No less than 270 mounds have been counted in the Bar. None of them has been excavated, but they serve to recall the ancient prosperity of the tract, which is testified to alike by the Greek his- torians and by local tradition. The most interesting architectural remains are the temples at Amb in the Salt Range, built of block kankar. The style is Kashmiri, and they date probably from the tenth century, the era of the Hindu kings of Ohind. Sher Shah in 1540 built the fine mosque at BHERA ; and the great stone clam, now in ruins, across the Katha torrent at the foot of the Salt Range is also attributed to him.

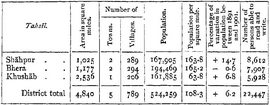

The population of the District at the last four enumerations was : (1868) 368,288, (1881) 42i,5 8 > (1891) 493,588, and (1901) 524,259, dwelling in 5 towns and 789 villages. It increased by 6-2 per cent, during the last decade. The Dis- trict is divided into three tahsils SHAHPUR, BHERA, and KHUSHAB the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named. The towns are the municipalities of SHAHPUR, the administrative head- quarters of the District, MIANI, SAHIWAL, KHUSHAB, and BHERA.

The following table gives the chief statistics of population in 1901 :

NOTE. The figures for the areas of tahsfls are taken from revenue returns. The total District area is that given in the Cenws Report.

Muhammadans number 442,921, or 84 per cent, of the total ; Hindus, 68,489; and Sikhs, 12,756. The density of the population is low, as might be expected in a District which comprises so large an area of desert. The language spoken is Western Punjabi, or Lahnda, with three distinct forms in the Jhelum valley, the Thai, and the Salt Range respectively. The last has been held to be the oldest form of Punjabi now spoken in the Province.

The most numerous caste is that of the agricultural Rajputs, who number 73,000, or 14 per cent of the total population. Next come the Jats (64,000), Awans (55,000), Khokhars (24,000), and Baloch (14,000). Arains are few, numbering only 7,000, while the Maliars, very closely akin to them, number 4,000. The commercial and money- lending castes- of numerical importance are the Aroras (43,000) and Khattris (16,000). The Muhammadan priestly class, the Saiyids, who have agriculture as an additional means of livelihood, number 10,000. Of the artisan classes, the Julahas (weavers, 25,000), Mochis (leather- workers, 19,000), Kumhars (potters, 15,000), and Tarkhans (carpenters, 14,000) are the most important ; and of the menial classes, the Chuhras (sweepers, 34,000), Machhis (fishermen, bakers, and water-carriers, 14,000), and Nais (barbers, 9,000). Mirasls (village minstrels) number 10,000, About 48 per cent, of the population are supported by agri- culture.

The American United Presbyterian Mission has a station at Bhera, where work was started in 1884. In 1901 the District contained 21 native Christians.

Agriculture

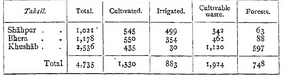

In the valleys of the Jhelum and Chenab, and in the plain between them, the soil is chiefly a more or less sandy loam, with patches of clay and sand. The Thai consists chiefly of sandhills, gricu tire, interspersed with patches of hard level soil and tracts of ground impregnated with salts, while in the hills a fertile detritus of sandstone and limestone is found, The conditions of agriculture, however, depend on the facilities for irrigation and not on soils, nd the unirrigated cultivation is precarious in the extreme. The District is held chiefly on the bhaiyachara and pattldari tenures, though zaniindari lands cover about 145 square miles and lands leased from Government about 5,000 acres. The area for which details are available from the revenue records of 1903-4 is 4,735 square miles, as shown below :

Wheat is the chief crop of the spring harvest, occupying 579 square miles in 1903-4, Gram and barley covered 92 and 19 square miles respectively. In the autumn harvest spiked millet (bajra) is the prin- cipal staple, covering 209 square miles; cotton covered 66 square miles, pulses 50, and great millet (jowar) 56.

During the ten years ending 1900-1, the area under cultivation increased by 19 per cent., and it is still extending with the aid of the new Jhelum Canal. There is little prospect of irrigation in the Thai, as, although it lies within the scope of the proposed Sind-Sagar Canal, the soil is too sterile to make irrigation profitable. Nothing has been done to improve the quality of the crops grown. Loans for the sinking of wells are appreciated in the tract beneath the hills and in the Jhelum valley; more than Rs. 5,800 was advanced under the Land Improvement Loans Act during the five years ending 1903-4.

There are no very distinct breeds of cattle, though the services of Hissar bulls are generally appreciated. The cattle of the Bar are, however, larger and stronger than those of the plains, and there is an excellent breed of peculiarly mottled cattle in the Salt Range. A great deal of cattle-breeding is done in the Bar, and a large profit is made by the export of ghl. Many buffaloes are kept. The Dis- trict is one of the first in the Punjab for horse-breeding, and the Shahpur stock is considered to be one of the best stamp of remounts to be found in the Province. A considerable number of mules are bred. A large horse fair is held annually, and 44 horse and 13 donkey stallions are maintained by the Army Remount department and 3 horse stallions by the District board. Large areas have been set apart in the Jhelum Colony for horse runs, and many grants of land have been made on condition that a branded mare is kept for every 2^ acres. Camels are bred in the Bar and Thai. A large number of sheep are kept, both of the black-faced and of the fat-tailed breed, and goats are also kept in large numbers. The donkeys, except in the Jhelum and Chenab valleys, are of an inferior breed, but are largely used as beasts of burden.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 883 square miles, or 58 per cent, were classed as irrigated. Of this area, 343 square miles were irrigated from wells, and 540 from canals. In addition, 107 square miles, or 7 per cent, of the cultivated area, are subject to inundation from the Chenab and Jhelum, and much of the land in the hills classed as unirrigated receives benefit from the hill torrents. The LOWER JHELUM CANAL, which was opened in October, 1901, irrigates the uplands of the Bar. The remainder of the canal-irrigation is from the inundation canals (see SHAHPUR CANALS), which, with the excep- tion of three private canals on the Chenab, all take off from the Jhelum. It is intended to supersede them gradually by extensions of the Lower Jhelum Canal. In 1903-4 the District had 7,545 masonry wells, worked by cattle with Persian wheels, besides 241 unbricked wells, lever wells, and water-lifts. Fields in the Salt Range are embanked so as to utilize to the utmost the surface drainage of the hills, and embankments are thrown across the hill torrents for the same purpose.

Forests

In 1903-4 the District contained 775 square miles of 'reserved' and 25 of unclassed forest under the Deputy-Conservator of the Shahpur Forest division, besides 21 square miles of military reserved forest, and 3 square miles of 'reserved' forest and 692 of waste lands under the Deputy-Com- missioner. These forests are for the most part tracts of desert thinly covered with scrub, consisting of the van (Salvadord), jand (Prosopis), leafless caper and other bushes, which form the characteristic vege- tation. The Acacia arabica, slusham (Dalbergia Sissoo\ and othei common trees of the plains are to be found by the rivers, and planted along roads and canals and by wells ; but as a whole the District is very poorly wooded. The forest revenue from the areas under the Forest department in 1903-4 was Rs. 77,000, and from those under the Deputy-Commissioner Rs. 59,000.

Salt is found in large quantities all over the Salt Range, and is excavated at the village of Warcha, the average output exceeding 100,000 maunds a year. Small quantities of lignite have been found in the hills south of Sakesar ; gypsum and mica are common in places, and traces of iron and lead have been found in the Salt Range. Petro- leum also has been noticed on the surface of a spring^ Limestone is quarried from the hills in large quantities, and a great deal of lime is burnt. Crude saltpetre is manufactured to a large extent from the earth of deserted village sites, and refined at five licensed distilleries, whence it is exported. The manufacture of impure carbonate of soda from the ashes of Salsola Griffithii is of some importance.

Trade and Communication

Cotton cloth is woven in all parts, and is exported in large quan- tities, while silk and mixtures of silk and cotton are woven at Khushab, and cotton prints are produced. Felt ru & s are made at that town and at Bhera ' Bhera also turns out a good deal of cutlery, and various

kinds of serpentine and other stones are used there for the handles of knives, caskets, paper weights, &c. The woodwork of Bhera is above the average, and good lacquered turnery is made at Sahiwal. Gunpowder Tnd fireworks are prepared on a large scale at several places. Soap is also manufactured.

Cotton is exported both raw and manufactured, and there is a large export of wheat and other grains, which will increase with the develop- ment of the Jhelum Colony. Other exports are wool, ghl, hides and bones, salt, lime, and saltpetre. The chief imports are piece-goods, metals, sugar, and rice.

The Sind-Sagar branch of the North-Western Railway crosses the north-eastern corner of the Bhera tahsil, and, after passing into Jhelum District, again enters the District, crossing the Khushab tahsil. The Jech Doab branch strikes off through the heart of the District, running as far as Sargodha, the head-quarters of the Jhelum Colony. There is also a short branch to Bhera. A light railway from Dhak to the foot of the hills near Katha, a distance of about 10 miles, is under survey, in the interests of the coal trade.

The District is traversed in all directions by good unmetalled roads, the most important leading from Lahore to the frontier through Shah- pur town and Khushab, and from Shahpur to Jhang and Gujrat The total length of metalled roads is 20 miles, and of unmetalled roads 838 miles. Of these, 13 miles of metalled and 26 miles of unmetalled roads are under the Public Works department and the rest under the District board.

The Jhelum is crossed between Shahpur and Khushab by a bridge of boats, dismantled during the rains ; and a footway is attached to the railway bridge in the Bhera tahsil. There are sixteen ferries on the Jhelum, those on the Chenab being under the management of the authorities of Gujranwala District. A certain amount of traffic is carried by the former river, but very little by the latter.

Prior to annexation, the greater part of Shahpur was a sparsely populated tract, in which cultivation was mostly dependent on wells and on the floods of the Jhelum river ; and although the District has been affected by all the famines which have visited the Punjab, it is not one in which distress can ever rise to a very high pitch. No serious famine has occurred since annexation, and with the con- struction of the Lower Jhelum Canal the Chaj Doab may be said to be thoroughly protected.

Administration

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, aided by two Assistant or Extra- Assistant Commissioners, of whom one is in charge of the District treasury. It is divided for administrative purposes into the three tahsils of SHAHPUR, BHERA, and KHUSHAB.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for criminal justice. Civil judicial work is under a District Judge; and both officers are subordinate to the Divisional Judge of the Shahpur Civil Division, who is also Sessions Judge. There are two Munsifs, one at head-quarters and the other at Bhera. The principal crime of the District is cattle-lifting, though dacoities and murders are not uncommon. In the Salt Range blood-feuds are carried on for generations.

VOL. XXII. P At the beginning of the nineteenth century the tract which now forms the District was held by various independent petty chiefs, all of whom were subdued by Ranjit Singh between 1803 and 1816. Till 1849 it was governed by Sikh kardars, who took leases of the land revenue of various blocks of country, exacting all they could and paying only what they were obliged. The usual modes of collection were by taking a share of the grain produce or by appraisement of the standing crops, and the demand was not limited to any fixed share of the harvest On annexation in 1849 the District was assessed village by village in cash, the Sikh demand being reduced by 20 per cent. ; but even this proved too high. In 1851 the distress found voice, and the revenue was reduced in the Kalowal (Chenab) tahsil from Rs. 1,00,000 to Rs. 75,000. In 1852 a summary settlement was carried out, giving a reduction of 22 per cent. In 1854 began the regular settlement, which lasted twenty years and resulted in a further decrease of a quarter of a lakh. A revised settlement was concluded in 1894, The average rates of assessment were Rs. 2 (maximum Rs. 3-10, minimum 6 annas) on 'wet' land, and R. 0-15-6 (maximum Rs. 1-9, minimum 6 annas) on ' dry ' land. These rates resulted in an imme- diate increase of 38 per cent, in the demand, the incidence per acre of cultivation being R. 0-15-9. The average size of a proprietary holding is 5 acres.

The collections of land revenue and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees :

The District contains five municipalities, SHAHPUR, BHERA, MIANI, SAHIWAT,, and KHUSHAB. Outside these, local affairs are managed by the District board, whose income, derived mainly from a local rate, was a lakh in 1903-4, while the expenditure was Rs. 85,000, education being the largest item.

The regular police force consists of 502 of all ranks, including 100 municipal police, and the Superintendent usually has one Assis- tant Superintendent and four inspectors under him. Village watch- men number 538. There are 17 police stations and 5 outposts. The District jail at head-quarters has accommodation for 280 prisoners.

Shahpur stands tenth among the twenty-eight Districts of the Province in respect of the literacy of its population. In 1901 the proportion of literate persons was 4-2 per cent. (7-5 males and 0-7 females). The number of pupils under instruction was 2,119 in 1880-1, 8,560 in 1890-1, 7,961 in 1900-1, and 8,495 * n x 9 3-4-

In the last year there were 7 secondary and 74 primary (public) schools, and u advanced and 231 elementary (private) schools, with 696 girls in the public and 293 in the private schools. The District possesses two high schools, both at Bhera. It also has twelve girls 5 schools, among which Pandit Diwan Chand's school at Shahpur is one of the best of its kind in the Province. The total expenditure on edu- cation in 1903-4 was Rs, 48,000, of which the municipalities contri- buted Rs. 5,800, fees Rs. 21,000, endowments Rs. 1,400, Government Rs. 4,000, and District funds Rs. 15,600.

Besides the civil hospital at Shahpur, the District has eight outlying dispensaries. At these institutions 109,428 out-patients and 1,463 in-patients were treated in 1904, and 4,977 operations were performed. The income was Rs. 17,000, the greater part of it coining from muni- cipal funds.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 12,072, repre- senting 23 per 1,000 of the population.

[J. Wilson, District Gazetteer (1897); Settlement Report (1894); Grammar and Dictionary of Western Panjdbi^ as spoken in the Shah- pur District (1899); and General Code of Tribal Custom in the Shahpur District (1896).]