Sikh shrines in Pakistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A backgrounder

Sandeep Rai, Aanchal Bedi, Oct 15, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, Aanchal Bedi, Oct 15, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, Aanchal Bedi, Oct 15, 2023: The Times of India

Pakistan has 345 standing Sikh shrines, over 100 of them directly connected to the first six Gurus. But only 22 are functional, and two collapsed in rains this year

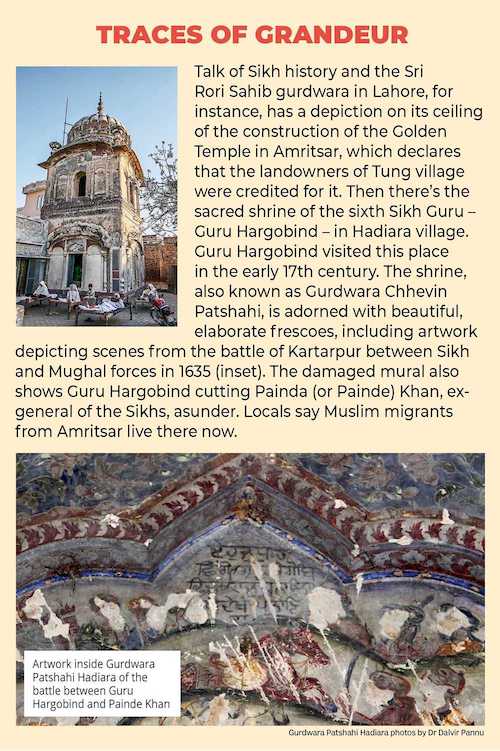

Not far from the Wagah-Attari border near Amritsar, in a village in Pakistan’s Lahore district, a gurdwara marks the spot Guru Nanak once used for prayer, sitting among pebbles and rocks with his companion Bhai Mardana. It was built in the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. But Sri Rori Sahib Gurdwara – ‘rori’ is Punjabi for pebbles – no longer stands at the site as the important symbol of Sikh faith that it is. Visit the place now and all you’d find is the portion of a wall and signs of the decades of neglect that finally led to the structure coming down in torrential rain on July 10 this year.

Sri Rori Sahib is a symbol of the condition in which numerous other gurdwaras find themselves today in Pakistan. For while the gurdwaras at Nankana Sahib, Panja Sahib, and Kartarpur Sahib are well-known and thronged by people from around the world, the majority of the gurdwaras in the Pakistani countryside have long cried out for care and attention. Among these are scores of gurdwaras associated with the first six Sikh Gurus.

“At present, there are 345 gurdwaras standing in Pakistan, of which 135 are directly connected to the first six Gurus. But at present, only 22 are functional. The rest have been left to their own fate,” said Lahore-based Noshaba Shehzad, an independent researcher.

Need For Ground Support

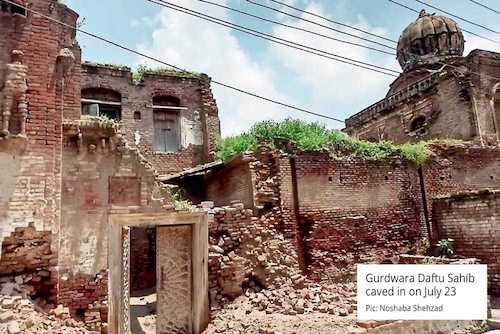

Sri Rori Sahib was not the only gurdwara to have crumbled in the monsoons. Gurdwara Daftu Sahib, in Daftu village of Kasur district, caved in on July 23. This was where the revered 17th century Sufi poet Baba Bulleh Shah is said to have taken refuge from Islamic fundamentalists. Bulleh Shah’s compositions and sermons are well-loved and popular among people on both sides of the border. And it is the people themselves who need to be made a central part of any efforts to save these gurdwaras, feel some experts.

“Spreading awareness about the secular narrative of Sikh traditions on which these monuments were built is imperative. A sense of belonging has to be nurtured in ground zero, the sooner the better. I strongly reject the idea of simply relying on the Sikh diaspora to pump in money for the restoration of these buildings without local support,” says Dalvir Pannu, the US-based author of ‘The Sikh Heritage – Beyond Borders’.

While the diaspora is not to be discounted, they do admit that there are limits to what they can achieve.

“I went to Pakistan in the late ’90s and tried to identify the many gurdwaras there. We’ve been able to restore a few but it’s a tough task in the face of local resistance and encroachment. Concerted efforts are needed from the Pakistan government and the international Sikh community to preserve our history,” said Balbinder Singh Nanuwan, president of the Khalsa International Welfare Society in the UK.

Harpreet Singh Sachal, a real estate developer from Canada, echoes Nanuwan. “Historic gurdwaras in the land where Sikhism originated are getting destroyed one after the other either due to a lack of maintenance or encroachment. Since the majority of Sikhs moved out after Partition, the last 76 years have witnessed utter neglect of these marvels of architecture. The international Sikh community has carried out some restoration work but what is needed is a collective effort,” he said.

Cradle Of Sikhism

The Pakistan government has an office for maintaining the estates and assets of those who left during the Partition, but it has not been very effective at preserving the gurdwaras in the country.

“Lahore is the cradle of Sikh history, but we’ve not been able to preserve it. The Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB) lacks teeth and only gets active during festivals. Its rights are also limited, so there is little scope for taking up the task of restoring historically relevant properties, including the gurdwaras lying in a dilapidated condition,” said Dr Kalyan Singh, the first Sikh professor in Pakistan since 1947. He teaches at the Government College University (GCU), Lahore.

A part of the problem has to do with the minuscule population of Pakistani Sikhs. “Minorities in Pakistan are too small numerically to enjoy any kind of influence. The Sikh population here is just about 20,000,” the GCU professor said. Kirpa Singh, an ETPB executive board member, agrees. “It is true that a little over 20 gurdwaras are functional in Pakistan. The reason is that the size of the Sikh population here is not enough to take care of the hundreds of gurdwaras scattered across the rural belt of Pakistan’s Punjab. At present, the community is mainly concentrated around Peshawar, Lahore, and a few other places,” he said.

Things are different wherever there is a presence of Sikhs, but maintaining the distant gurdwaras can be challenging. “Those who live in big cities have their business establishments and jobs there. It is not possible for them to migrate to remote villages to look after the shrines there. In the absence of Sikhs in such areas, it makes little sense to restore abandoned gurdwaras. Nonetheless, we do make efforts to not let such structures collapse and keep repairing them from time to time,” Kirpa Singh added.

Solutions Near And Far

There are examples of gurdwaras being converted to schools, houses and places of worship. Built in 1937, Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha on Kashmir Road in Mansehra city of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan currently houses a municipal library. In 2021, ETPB decided to take over possession and open it for the local Sikh community to offer prayers. Similarly, another gurdwara in Sargodha city is now the Government Ambala Muslim High School.

Finding new uses for these structures ensures that they receive suitable attention though Haroon Khalid, the Pakistani author of ‘Walking with Nanak’, does note that protecting their historical value becomes difficult in such cases.

“These instances should not be seen as Hindu spaces being occupied by Muslims. In the people’s imagination, these places are still sacred. However, since the context has changed, they express their sacredness in a way or language known to them. The idea is to retain the sanctity of a particular place even if it means giving it a new identity. But the fallout is that the history linked to it might also be forgotten as it’s not part of the discourse anymore,” he says.

Over in India, Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) president Harjinder Singh Dhami said they are “ready to contribute to this noble cause in whatever way the neighbouring country’s government and their Sikh body may deem fit”.

“Sikh shrines left behind in Pakistan represent the genesis of our faith that was propagated by Guru Nanak Dev and carried forward by successive Gurus. We strongly feel that the Pakistan government must focus on the restoration of at least those gurdwaras that have historical relevance. Pakistan Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (PSGPC) and ETPB should assign responsibility among local community members to ensure that the gurdwaras are well-maintained,” he said.