Vanjari: Deccan

Contents |

Vanjari

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Vanjari — carriers, cultivators, cart-drivers and labourers, found scattered almost all over the dominions.

History

ln the districts of Parbhani and Bhir, where they muster strong, th^ have a tradition that they came from the north about tt*ee hundred years ago. They are believed to be descended from the migratory tribes who, under the general name Banjaras, canied grain, tobacco, &c., on pack bullocks, from market to market, and from the interior to the sea-shore, whence they brouglrf back salt to inland towns. Th^y probably came into the Deccan with the forces of the Moghul Generals, by whom they were engaged to carry provisions and supply the armies with corn and -fodder. Owing to the opening of cart roads and railways. their occupation Jis grain carriers has suffered during the last seventy yearsj and although a few of the Vanjaris still follow their original calling, the bulk have settled down as peaceful culti- vators and are now hardly distinguishable from the local Kunbis. Their early settlements in the Deccan were probably the highlands of the Balaghats, whence colonies appear to have spread over the low lying plain as far east as the District of Warangal.

The word Vanjari is only a variant of the Hindi Banjara (Sanskrit, Ban — forest, char — to wander), the Hindi ' ba ' being changed into the Marathi ' wa ' as in the cases of the Hindi ' Bana ' into Marathi 'Wana,' Baidya into ' Vaidya,' ' Bania ' into " Wani ' and so on. The Vanjaris, however, resent this origin and claim to be a branch of the Marathi Kunbis. Their striving after social dis- tinction has not yet proved successful, as they are still looked down upon by the Maratha Kunbis.

Origin

Regarding their origin Mr. Kitts, (the Berar Census Report, 1881), says : — "The Vanjaris claim to be of Maratha origin.

They are a race of Kshatriya origin, belonging to the east of India, and mentioned by Manu as among those wljp, by the omission of holy , rites and neglect to see Brahmins, had gradually 4unk to the lowest of the four classes. They assert that, with other castes, tKey were allies of Parshuram, when he ravaged the Harihayas andthe Vindhya mountains, and that the task of guarding the Vindhya passes was entrusted to them. From their prowess in keeping down the beasts of prey which infested the ravines under their charge, they became known as the 'Vanya Shatru,' subsequently contracted into Vanjari." To confound them with the Banfara carrier castes, whose name ' Vancharu ' means ' forest wanderers ' iS to give them great offence. In religion they are often Bhagwatas. They practise early marriage and in nearly every point resemble Kunbis. The caste is, in the main, agricultural."

The ingenuity displayed in deriving the name Vanjari from 'Vanajari' (Vanaja — wild beasts and Ari — enemy or destroyer), or Vanya Shatru is remarkable, but fails to explain satisfactorily the connection of the caste with the Marathas. Their legend also throws no light upon their origin and is apparently devised to raise the caste in social estimation. •

Internal Structure

The Vanjaris of the Hyderabad Terri- tory are divided into two sub-castes: (1) Ladjin Wanjari and (2) Raojin Wanjari, the members of which eat together but do not intermarry.

The Lad Vanjaris, like the other Lad castes of the Dominions, * probably hail from 'Lat' the ancient name of the southern Gujarath, which included Broach, Ujjain and Nasik. How wealthy and opulent these people were and how extensive was the trade they carried in their palmy days will be perceived from the following quotation. (Bombay Gazetteer, Vol. XVI) : —

"The Vanjari story of the great Durga Devi Famine, which lasted from 1396 to H07, is that it was named from Durga, a Lad Vanjari woman, who had amassed great wealth and owned a million pack bullocks which she used in bringing grain from Nepal, Burmah and China. She distributed the grain among the starving people and gained the honourable title of ' Mother of the world,' Jagachi Mala.' With the construction of the Railways and the increased use of carts thei.% nomadic trade guilds broke down and th» Lad Vanjaris settled as cultivators on the soil of the Deccan."

The Lads are chiefly found in Aurangabad and Parbhani Districts. Raojin Vanjaris are found in the districts of Bhir and Nander. The derivation of their name is uncertain, nor have the members of this ssb-caste any traditions which will give a clue to their origin or to the period of their immigration. In physical appearance the members of both tjje sub-castes resemble each other and differ little from the Maratha Kunbis, to whose manners, customs and usages they now mostly conform. A portion of the Raojin Vanjaris have migrated to, and settled in, the Telugu Districts of Indur, Warangal and Nalgundah and though they have adopted the local customs, manners and language, they have still 'preserved their Maratha names (with the affix, 'ji' as, Ramaji, Vyankoji, &c.), and Maratha sur-names and the worship of the Maratha deities. There are indica- tions, however, that these new settlers, like brethren in the Maratha- wada, are fast losing their tribal identity and, in a generation or two, will be entirely absorbed in the mass of the people by whom they are surrounded.

Each of the sub-castes, above referred to, is further sub- divided into two endogamous groups, Baramasis and Akarmasis, the latter being composed of the illegitimate descendants of the former. Intermarriages and community of food are prohibited between these two classes.

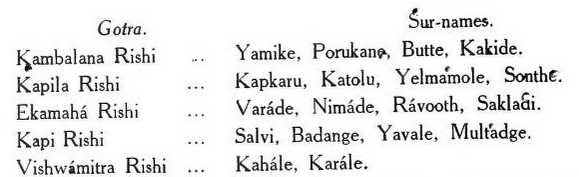

The Vanjaris profess to have twelve gotras, each of which is again sub-divided into four sub-septs or family groups.

The gotras with sur-names attached to each are given below : — Golra. Sur-names.

Atma Rishi ... Dhatrak, Parad, Pindike, Ranmale.

Rangu Rishi ... Hamandi, Navathe, Mole, Dahithe.

Bagama Rishi ... Kanganti, Apale, Kanare, Korde.

Vashistha Rishi ... Kale, Kole, Sankle, Tidke.

Kasypa Rishi ... Karipe, Naik, Lalgote, Bharashanker.

Katipa Rishi ... Korike, Rangte, Ramanwi, Sangle.

Amba Rishi ... Lavange, Bodke, Pandarbate, Avade.

The gotra system is peculiar to the Vanjaris and serves to, dis- tinguish them from the Maratha Kunbis. It is still oljperved in the Telugu Districts, but in Marathawida it is falling into disuse and giving way to the exogamous sections Based upon family names. ^Thui with the Maratha Vanjaris the gotras are* exogamous only in theory for, in actual life, families bearing the same sur-name are debaned from intermarriages. The fifty family names (kulis), which comprised the early exogamy of the Vanjaris, have been, of late, developed Into numerous others, a list of some being attached to this article. This development probably deranged the gotra system and was, no doubt, due to the multiplication of the original families and their consequent distribution over a wider range pi country. The Vanjari sui-names, with a few exceptions, have evidently been borrowed from the Maratha Kunbis. These facts tlearly mark the stage of transition through which the Vanjaris are rapidly passing, so that in course of time they will be so completely welded with the Maratha Kunbis as to obliterate all traces that distinguish the two races from one another.

A man must marry within his sub-caste, but cannot marry within his section. Marriage with a mother's sister's daughter or a father's sister's daughter is not allowed. It may be allowed with the daughter of a maternal uncle. A man may marry two sisters, but two brothers cannot marry two sisters. Adoption is practised, in which case the adopted boy must belong to the same section as his adoptive father. Subsequent to his adoption the boy is not allowed to marry in the sections of both families.

Marriage

Both infant and adult marriages are in force. Sexual indiscretions before marriage are not tolerated and should an unmarried girl become pregnant she is turned out of the caste. Polygamy is permitted theoretically to any extent.

The negotiations towards marriage are opened by the fathet of the boy and if the results are satisfactory an astrologer is re- quested to compare the horoscopes of the bride and bridegroom and ts see if the proposed match will be auspicious and happy. On an auspicious day the betrothal of Kunku Lavme ceremony is performed at the girl's house, when the gods Ganesh and Varuna are worshipped, clothes and cocoanut pieces are presented to the girl and a mark is made, with ^unkyan, upon her forehead. The same ceremony having been gone through at the boy's house, a date is fixed for the celebration of masiage and invitations are sent to kinsmen and 'friends. A few days before the wedding, Bir Kdrya is solemnised. Deceased ancestors, represented by embossed plates, are placed in a doli (a sort of litter) and carried to the Maruti's temple, the procession being headed by a man dancing fantastically and flourishing naked swords. To the god Maruti are offered two pounds of cooked rice, the offering being thrown by handfuls on either side of the way as the procession returns home. The ancestors are restored to their seats and caste people are feasted in honour of the occasion. Generally, between one and five days before marriage, the bjide and the bridegroom and their parents are smeared with turmeric and oil. Among the Vanjaris the wedding precedes Deookfl Karya, or the enshrinement of the marriage guardian deity, which is represented by Pdnch Pallaoi, or the leaves of five trees. Viz., the Mango {Magnijera indica), Jdmbul (Eugenia jambolana), Umbar {Ficvs glomerata), Samdad (Prosopis spicigera) and Rui (Calo- tropis gigantea). A manied couple, related to the bride or bridegroom, have the skirts of their garments fastened in a knot and are taken under a canopy of cloth to the Maruti's temple. The woman bears in her hand a bamboo basket containing a winnowing fan, uncooked articles of food and a wheat cake coloured with turmeric, while her husband holds a rope and an axe. At the temple, the pair are received by the Gnrava, or the god's priest, who takes the god's offering contained in the basket and ties the Panch Pallaois with the rope to the axe. This done the party return home and fasten the sacred twigs to the wedding post. On this day the couple bringing the Devaka axe required to observe a fast.

On the wedding day the marriage procession is formed at the house of the bridegroom who is conducted to ijie house of the bride. There, under the wedding canopy, the betrothed pair are made fe stand face to face on bullock saddles and a curtain is held between them by the family priest. After the recital of auspicious mantras, the priest weds the couple by throwing grains of rice over their heads. This is followed, on the removal of the curtain, by the Kanyadgn ceremony, or the presentation of the bride to the bridegrc^im and his acceptance of the gift. The bridegroom tben puts the mangalsutia round the bride's neck and the priest fastens \an\anams, or thread bracelets, on their wrists. Here a singular ceremony is performed. A washerwoman sprinkles oil over the wedded couple with betel leaves tied to an arrow. She afterwards dips two areca nuts into water, bores a hole into each and binds them, each with a woman's hair, on the right arm of the bride and the bridegroom respectively. The newly wedded pair are next seated on the earthen platform built under the canopy and throw clarified butter into the sacred fire (Homo) kindled by the priest. After this they ar^ presented with clothes and coins by the assembled guests. With the corneK of their clothes knotted together, the young couple then pass* round, make obeisance to the family gods and elderly relatives and finally bow to the bride's mother who unties the knot of their garments. On the performance of the zdl ceremony, at which the bride is entrusted to the care of the bridegroom's parents, the bridal pair are seated on horseback and taken in procession, first to the Hanuman's temple and thence to the bridegroom's house. A grand feast to the caste people terminates the proceedings.

The Telugu Vanjaris marry their daughters as infants between the ages of five and twelve. They allow their girls to cohabit prematurely, a practice which is not tolerated by the Maratha Vanjaris. Their marriage ceremony is modelled after the fashion of the Telugu castes and comprises : —

The worship of patron deities and deceased ancestors; Prathdnam, Kottanam, Airani Kundalu, Maildpolu, Lagnam, Kmydidn, Pddghattanam, Jilkar Bdlam, Kankanam, Talwdl, Brahmdmodi, Bdshingam, Ndgvells, Pdnpu, &c. All these cere- monies have been'fully described in an article on the Kapus. At the performance of the Nfgvelly ceremony goats are sacrificed and caste jieople are feasted. No pusti is worn by the Telugu Vanjari females who? it is alleged, were deprived of it by Wayu, the god who presides 'over air.

Widow-Marnage

Widow-marriage is permitted, the widow bemg expected not to marry any member of her late husband's family. She IS also not to marry a bachelor unless he is previously wedded to a Rui plant. The ritual tsed at a widow marriage (Mohtar) is very simple. On a dark night the widow and her proposed husband are seated side by sid5 with their clothes knotted by a Brahman. Five areca nuts are placed on a wooden stool in front of them and on the bridegroom pushing them away, with the end of a sword, from off the stool the pair become husband and wife.

Divorce

Divorce is allowed on the ground of the wife's adultery, or if the couple cannot live in harmony. It is effected by ihe expulsion of the adulterous woman in the presence of the caste Panckdyaf.

Inheritance

The Vanjaris follow the Hindu Law of Inherit tance.

Religion

The Vanjaris worship all the Hindu divinities but special reverence is done by them to their patron deity Khandoba of Jejuri, in whose honour a Gondhal dance is performed after the completion of a marriage. Other deities, Bhavani of Tuljapur and Mahur, Bhairoba, Mhasoba, Mari Ai, are also honoured with a variety of offerings. They observe all the Hindu festivals principally Akshatritiya in Vaishakha (May), Nagapanchami in Shravana (August), Dassera in Aswin (October) and Shimga in Falgun (March). Their priests are Deshastha Brahmans and their Gurus, or spiritual guides, are Gosavis.

The Telugu Vanjaris are Vibhutidharis and the followers of Aradhi Brahmins. (A few of them have been converted to Lingayit- ism and conduct their religious observances under the guidance of Jangams, the Lingayit priests). They appease Pochamma, Ellama and other minor gods of Telingana with offerings of fowls, goals and sweetmeat; but the cult of Khandoba and the worship of deceased ancestors, which are characteristics of Maratha Vanjyjis, still prevail among them and play a prcHninent part in their religion.

funeral Ceremonies

Vanjaris usually 'bury fheir dead. Cremation is also resorted to and is becoming more genej^l. Children and persons dying of accident are buried. A male corpse is bome to the cemetery in white and a female in green clothes. On the 1 0th day after death the chief mourner shaves his moustaches, offers rice balls for the benefit of the deceased and' provides a funeral feast for the caste people. On the 13th day he is required to feed a Gosavi. The Lingayit Vanjaris bury theil dead in a sitting posture with legs folded and ^with a Lingam plagued in the 'hands. The manes of ancestors are propitiated on the 3rd day of the light half of Vaishakha (May) and on the Pttra Amavasya day (middle of September).

Social Status

The social status of Vanjaris is nearly as high as that of Maratha Kunbis and Telugu Kapus, from whose hands they eat cooked food. In respect of diet they eat mutton, fowl, fish, deer, hare and indulge in strong drinks. They abstain from pork, deeming the pig the most unclean of animals. Tlfey do not eat carrion or the leavings of other people.

Occupation

Originally grain carriers and cattle merchants, most of the Vanjaris have now taken to cultivation, and hold lands on permanent and other tenures. They are patels of villages, but a few have risen to the status of zamindars or landlords. The poorer members of the caste are personal servants, cart-drivers and landless day labourers. A few still cling to their original occupation as carriers of grain and cattle merchants and rear bullocks and sell them at a profit in distant markets. The Vanjaris [rave caste Panchayats to whom social disputes and caste quarrels are referred for settlement. The decisions of these bodies are enforced on pain of loss of caste. The members of the caste do not wear the sacred thread.