Kumbh, Maha Kumbh, Ardh Kumbh: Allahabad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Mahakumbh, its meaning, significance

Triveni Of Gyan, Bhakti And Karm

Meena Om, January 23, 2025: The Times of India

The human body is like a pot; whatever exists outside also resides within. That which forms the Brahmand, Universe, also constitutes us. Thoughts sent out to the Universe inevitably come back. The vortex of negative thoughts, information and energy we create, too, boomerangs.

The Mahakumbh is an occasion to cleanse the body, mind, and soul by fostering positive thoughts and generating higher energy. Many take a dip at the Kumbh to wash away their sins, though bathing in the sacred River Ganga at any time has the same effect.

Usually, self-aware individuals make sankalps, pledges, during the Kumbh, offering their shortcomings, dishonesty, or addiction to holy rivers. Symbolic rituals, like discarding a small piece of gold, signify detachment from material obsessions.

However, the true significance of Kumbh is that it offers an opportunity to be on the path of jnan, by tasting jnan amrit, the nectar of self-realisation and wisdom, which enhances one’s unique individuality. The wisdom imparted by gurus and swamis at this grand congregation elevates spiritual growth. Prayagraj hosts the sangam, a confluence of three sacred rivers: the Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati, known as Triveni. Vedic texts emphasise harmony of body, mind, and soul, each represented by these rivers.

The Ganga purifies the body, the Yamuna heals the mind, and the invisible Saraswati enhances the soul. Saraswati, named after Ma Saraswati – the goddess of wisdom and sadbuddhi, good sense – symbolises the flow of true knowledge. In Kali Yug, information abounds, but wisdom remains obscured. The river became ‘lupt’, disappeared, as humanity prioritised indulgence over wisdom. The Saraswati might resurface, and society may collectively evolve by following the path of truth. Each yug is governed by three symbolic divine powers. At the onset of a yug, Maha Saraswati dominates, fostering wisdom, learning, and scientific progress. Saraswati thrives through sadhana, penance.

As the age advances, Mahalakshmi’s influence grows, bestowing material prosperity. Over time, Lakshmi’s dominance eclipses Saraswati, leading to societal decline as materialism takes precedence. When an imbalance arises, Mahakali force descends, destroying imperfections. This cycle is Nature’s way of evolution.

Mahakali acts through five elements – in the form of forest fires, volcanic eruptions, floods, earthquakes, global warming, and wars. Although global consciousness is awakening but the gap between information-based knowledge and wisdom has widened. Unlived and unrealised knowledge often feeds ego. We must shatter the ego and false identities to realise, ‘i am nothing, just a medium for universal laws of truth, love, karm, and light.’ Practising dhyan, meditation and contemplation daily aligns an individual with cosmic energies, enhancing personal growth. Working on the self, enables one to sow the seed for universal oneness and harmonious coexistence.

Though Kumbh has its relevance, for those in constant communion with Parmeshwar, the supreme entity, and praying for the welfare of all jada-chetan, matter and being, the saying of Saint Raidas, ‘Mann changa toh kathauti mein Ganga’– when the heart is pure, the Ganga is present even in a small wooden basin, conveys the spiritual truth.

History, evolution

Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

PRAYAGRAJ: Allahabad has a new name, the city also has a new look.

From the railway station to the civil lines, from Arail village to the Sangam area, about 300 murals have brightened the city’s landscape. Even the trees on the Arail road have been painted in bold, barking colours. Kumbh 2019 is less than a fortnight away and Prayagraj already looks like an open-air art gallery.

The murals are largely Hindu mythological in content. Scenes of Samudra Manthan mentioned in the Puranas have been recreated. In times when building a Ram Mandir in Ayodhya is among the hottest political topics of the season, Ram, Sita and Hanuman are well-represented on the city’s walls. One of them, in flaming red and bold yellow, just says “Jai Shri Ram”. Medieval saints such as Kabir and Sankaracharya also find a place. So do scenes from the common pilgrim’s life: women praying at the ghats, for instance. Buildings have been symmetrically painted to create the feel of a temple in some murals.

The painted trees depict a wide variety of animals. Looking at them a child can be taught to spot a penguin, a zebra, a giraffe, and more. Some are just geometric representations. The angry Hanuman is one of the paintings. The initiative is inventive but it does raise the question whether the paint would end up hurting the trees. “Tree-friendly painting material was used to ensure that their health is not damaged,” says Ashish Kumar Goyal, commissioner, Allahabad.

DM (Kumbh Mela) Vijay Kiran Anand says the idea of “Paint My City” was to ensure community participation. “It was meant to conserve heritage and beautify the city as well as highlight Union government campaigns such as Namami Gange,” he says. Among the flagship programmes of the Narendra Modi government, the project had the ambitious objective of reducing pollution of the river and help its rejuvenation. Quite a few murals carry the Namami Gange logo.

The painting of Prayagraj has generally resonated positively in the city. Interior designer Satyendra Pratap Singh is one of those who appreciates the city’s new look. “The religious paintings give a sense of what Allahabad is, a punya bhoomi. The whole city looks like an ashram,” he says. Harishankar Patel, who runs a sweetshop in Arail village, says the street art has transformed his village even though fretful pigs run amok on a garbage heap next door.

Several organisations, such as Delhi Street Art, took part in the project. “About 100 painters with street art experience from my team alone were involved in the job from October to December. Five of them came from foreign countries such as the UK, Russia and US,” says Yogesh Saini, founder, Delhi Street Art.

However, social scientist Badri Narayan bemoans the lack of representation given to all communities in the murals. “Allahabad was also a seat of Sufi knowledge but that aspect of the city doesn’t find any representation. It would have been nice if poets like Akbar Allahabadi and Firaq Gorakhpuri (real name: Raghupati Sahay) were given space,” says Narayan, director, Gobind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute. Renowned litterateur Harivansh Rai Bachchan is among those who does.

Novelist Neelum Saran Gour points out that the city has three co-existing and interlinked narratives: Indic, Islamicate and European. “However, the walls and the trees show only one of the three. The freedom struggle, to which Allahabad was central and integral, is missing,” she says.

From Harshvardhan’s Magh mela to the Raj-era Kumbh

Avijit Ghosh, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

Academic and author Neelum Saran Gour was born and bred in Allahabad. One of her works is about the culture and history of the city. A professor of English at the University of Allahabad, she speaks with Avijit Ghosh on her memories of the Kumbh mela, the rising politicisation of the festival and the changes it has brought to her city:

What are your memories of the Kumbh mela?

For me as a teenager, Kumbh meant waking up in the winter cold to the sound of endless footsteps. These were thousands of pilgrims coming in from surrounding villages and walking by our home. I was not deeply into the religious side of Kumbh. My husband’s family used to do the kalpawas. You stay by the Sangam for a month and observe certain rules of restraint. They used to rent a tent and carry the entire kitchen with them. Even the dog used to be there. It was something like a picnic.

The Kumbh was something for the city to enjoy. It was religious no doubt. But it was quietly religious. It was dignified and serene; a quiet, spacious and easy affair. Kalpawas was a private choice. Kumbh did not impact the consciousness of the people. The infrastructure of the city remained untouched by the festival. The Kumbh area had tents and lights. But it was all very simple compared to the present.

What’s different now?

In our childhood days, the Kumbh wasn’t an event trumpeting in your eardrums. In 2013, we couldn’t go to the Sangam due to traffic congestions and the detours. It was impossible for the ordinary citizen to visit the festival without getting utterly exhausted. In 1977, we had walked across the Kumbh nagri. We were younger then, but it was also easier to do so. Due to the growing scale, locals like us find it difficult to visit now. We managed to visit the area even during the Ardh Kumbh in 2007. But in 2013, we just could not go. We went when it was all over.

I sensed the political noise for the first time in 2013. The big hoardings talking about Hinduism being in danger. It was the Hindutva forces, the VHP. There was something different and combative in the air. We bought a trident at Kumbh in the 1980s. Today the trident has become a symbol of aggression. It wasn’t before. I like the idea of trident. The yogi plants it before himself when he meditates alone in the wilds of the mountains with the fire burning. It is a symbol separating the life of the saintly solitude from the chaos of the ordinary world. I never looked upon it as a weapon of militancy. Which is why I have never taken it off the wall.

The Kumbh was never called the Kumbh. The whole idea of Kumbh was constructed during the British period by the Prayagwals, the pandas on the banks of the river. Earlier, it was called the Magh mela and King Harshvardhan started it. Although the Magh mela, as attested by Chinese travellers, was a multi-religious conclave for Buddhists, Shaivites and sun worshippers who received generous endowments from Harshvardhan, it also witnessed scenes of sectarian clash and conflict.

Is Kumbh 2019 about making a political statement?

Yes, it is a power spectacle. And I do think that it has something to do with the 2019 election. The festival draws practising Hindus from all over India. It is very convenient to bring them all together at one site. I often think that it is using religion for extra-religious ends. The vast multitude comes for their own purpose. At the same time, if these signals are being thrown from all sides, there may be some impact. If it is there in every hoarding, in every pravachan, there could be an accumulative impact.

The Kumbh preparation has recast Allahabad as a city. What is your take?

The roads have been broadened. It is very good news for a city that is filling up with more and more vehicles every year. But we are not happy about so many trees being felled. Maybe new plantations will replace the lost trees. And one doesn’t know the kind of material being used when there’s a haste to finish projects. So much of historical value has been damaged. A Mughal doorway near Khusro Bagh which had great historic value has been pulled down. That could have been avoided.

In other countries, people are so mindful about heritage. Here there has been a domineering disregard for that. However, I am happy to see the new roads. The illegal encroachments deserved to be pulled down. In all fairness, I am happy to see the different shape being given to the city. I am optimistic that we will find a better city at the end of it.

A platform for nationalist sentiments: 1858-1998

Adrija Roychowdhury, Jan 9, 2025: The Indian Express

On November 1, 1858, a grand durbar was organised at Allahabad in what is today known as Malaviya Park. The Viceroy, Lord Canning, read out the historic proclamation of the Queen which would end the 250-year rule of the East India Company, and thereby transfer the government directly to the Crown. One crucial aspect of the proclamation was the promise that henceforth there would be no interference on religious matters on the part of the government, and that Indians would retain their autonomy on the practice of the religion.

Although Canning’s speech was attended by only a few Indians, the implications of what he said were surely not lost upon them. Allahabad-born freedom fighter and educationist Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, whose politics was closely tied to religion, labelled the Queen’s Proclamation to be a Magna Carta. The site of the proclamation had its significance too, Allahabad would soon become a major centre of politics and religious gatherings, including the Maha Kumbh which is hosted every 12 years.

Allahabad and the making of a modern Kumbh Mela

There is a widely held belief that the Kumbh Mela is an ancient religious gathering, or rather it is ageless. Historian Kama Maclean, who is a leading authority on the history of the Kumbh Mela, has suggested in her works that this very idea of timelessness is what gives a sense of sanctity to the Mela in the eyes of its followers. Maclean is among a group of historians who suggest that the present character of the Kumbh Mela — held at Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik and Ujjain every 12 years — is a recent development that can be dated back to the late 19th or early 20th century.

James Lochtefeld in his work, The Construction of the Kumbh Mela (2004), writes that the earliest references to the Kumbh Mela would make it clear that the name was only associated with the mela at Haridwar. In an interview with indianexpress.com he says that “this mela’s timing is astrologically determined.” “Haridwar is the only place where the Kumbh rashi (Aquarius) is the determining factor,” he says, explaining the origins of the name.

Lochtefeld also cites two texts, one written in 1695 and another in 1759, which state that only the Haridwar mela was specifically called ‘Kumbh’. These texts explicitly describe other festivals now identified with the Kumbh Mela cycle – the Magh Mela in Prayagraj and the Simhastha Mela in Nashik and Ujjain. These other pilgrimage festivals, while also important, were unconnected with the Haridwar Kumbh Mela.

It is only much later that the different festivals in the four cities came to be identified with the Kumbh Mela. Maclean in her book, Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765-1954 (2008), argues that the Prayag Kumbh Mela began only from the latter half of the 1800s and was instituted by the Prayagwals who were local pilgrimage priests. This was a way for them to concentrate pilgrim traffic for longer periods than the annual Magh Mela. “The Prayagwals basically wanted to bulletproof their festival in the face of terrible retribution by the British. They wanted this larger connection to give the Magh Mela even greater religious authorit, and thus make it more difficult to cancel,” says Lochtefeld.

Lochtefeld argues that the akhadas (traditional groups of Hindu ascetics that participate in the Kumbh Mela) were the main players who were involved in creating a nexus of these four cities through the Kumbh Mela. “With the decline of Mughal power in the 1700s and a power vacuum being created in North India, the akhadas emerged as powerful forces,” he says. “They had money and land and carried out trade, much of which happened at these festivals.”

The akhadas used their powerful networks to coalesce at this period and first establish themselves through the Kumbh Mela at Haridwar, Allahabad and Nashik. Ujjain was added to this nexus later. It is the mela at Prayagraj or Allahabad though that emerged as the largest, a stature it continues to hold.

Maclean in her work explains the position of significance that Allahabad acquired in the years following the 1857 revolt. After the devastation at Agra, the capital of the North-Western provinces was relocated to Allahabad. The city was planned and rezoned to make it safe for the European population. By the late 19th century, Allahabad was no longer referred to as a ‘mofussil’ and was instead given the epithet of the ‘Queen of the North’. The city “was considered to be the most extensive and successful example of formal planning in British India,” notes historian J B Harrison in his article ‘Four Gridirons’ (1986).

Allahabad became a seat of government and public life. A High Court was established in 1867, the Muir Central College in 1877 and the Allahabad University in 1887. The city would soon come to be inhabited by a thriving student population, who along with the existing influential Indian families and the Prayagwals, would form the local roots of the early Indian National Congress. “This political nexus was to have significant consequences for the Allahabad Mela,” writes Maclean.

From the late 19th century onwards, the Allahabad Kumbh Mela would become a platform for staging nationalist sentiments through religious activities. “Part of this was because of the British government’s policy of not interfering with religious affairs. So religion became a theatre for nationalist activities,” says Lochtefeld. He gives the example of the Ganesh Chaturthi which became a nationalist festival in the 1890s. The Kumbh too began to carry out a similar function.

A stage for nationalist ideas

One of the first changes to affect the Kumbh Mela was the emergence of an influential Hindu ‘lobby’ that wanted to create a space within the colonial state where Indian political sovereignty was respected. “In the hands of this lobby, the festival began to change, as these early nationalists argued in sophisticated terms that religious rites had become rights,” writes Maclean. Consequently, the mela’s character began changing from an syncretic, eclectic kind to one that conformed to the notions of a “Hindu religious festival”.

One aspect of this change was in the kind of products that were put up for sale in the fair. In the early part of the 19th century, the mela attracted luxury products from as far as Persia. British travel writer Fanny Parks noted the presence of pearls, semi-precious stones, bows and arrows, sable and dresses, and Persian and Arabic books in the mela of the 1830s. Contrarily, from the latter part of the century, devotional goods including trinkets, tracts, religious paraphernalia, idols of Hindu gods and goddesses, puja supplies and the like began appearing.

At the same time, the presence of non-Hindus was increasingly tolerated less. As Maclean notes, Muslim barbers doing ‘mundan’ or selling flowers and other paraphernalia, or simply attending the fair, which was common earlier, was now disliked. Similarly, there were frequent complaints against the missionaries preaching colonial propaganda at the site, a phenomenon that had been common in the last several decades.

From the beginning of the 20th century, the Kumbh Melas became a site where nationalist ideas were disseminated. “As nationalism developed, the hub of politics emanating from Allahabad’s notables, such as Motilal Nehru, Madan Mohan Malaviya and Purushottam Das Tandon, gave it a national reputation, giving the pilgrimage an extra dimension,” writes Maclean.

The pilgrimage manuals from the early 20th century onwards, for example, began suggesting pilgrims to also visit the secular sites of Allahabad, such as Minto Park (later known as Malaviya Park) and Anand Bhavan, home of Motilal Nehru.

Jawaharlal Nehru in his writings had mentioned about pilgrims, who after taking a bath at the Sangam, would often visit the Bharadwaj Ashram, across his home. “Curiosity, I suppose, brought most of them, and the desire to see well known persons they had heard of, especially my father. Our political slogans they knew well, and all day the house resounded with them,” he wrote.

Historian William Gould in his book Hindu Nationalism and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial India (2004) notes that the Congress leaders in the course of the 20th century would make direct use of the religious festivals and religious spaces “during processions and political meetings.” At the Magh Mela and the Kumbh Mela, he writes, the “Congress had established permanent camps.” During the 1907 mela, for instance, there were reports of Hindu ascetics preaching swadeshi and nationalism. The local press of the time had published its approval of this development as a task befitting sadhus as exemplars of the nation, writes Maclean.

The 1907 mela was also attended by nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak, causing much apprehension among the British authorities, who were conscious of the political furore created by his Ganapati festivals. Tilak’s meeting at Allahabad was attended by a small group of eager students, who went about communicating the message of swadeshi to the pilgrims on the mela ground. His visit was soon followed by that of the moderate leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Both leaders’ presence at Kumbh was part of their efforts to propagate their respective parties’ positions with regard to the national movement. When Tilak passed away a few years later in 1920, his ashes were brought to Allahabad where they were immersed in the Sangam during a ceremony that was attended by his colleagues, including Motilal Nehru. The poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan, who was present at the event, is known to have commented about the ceremony as being almost a pilgrimage.

By the 1930s, the mela was being used actively by the Congress to spread the message of civil disobedience. Gould in his book writes that at the Kumbh and the Magh Melas of the opening weeks of 1930, sanyasis played a leading role in turning the festivities into political rallies. On January 13, fifteen sanyasis held a procession where they sang a national song at the Haridwar mela. A similar procession, accompanied by a national flag, was carried out on the same day in Allahabad. Meanwhile, pamphlets were circulated by the Arya Samaj leader Swami Parmanand asking people to abstain from intoxicants and foreign-produced goods. The calls of the sanyasis, suggests Gould, “knitted Congress policy with religious sanctions.”

Maclean observes that one of the greatest statements of political mobilisation was found in the 1936 Ardh Kumbh Mela. The Swadeshi League had displayed an idol of Bharat Mata at their camp which was attended by a large number of visitors. In what would appear as a counter, the British authorities displayed a large figure of a sadhu on a high platform, fitted in with a loudspeaker.

While the Kumbh was used to convey political messaging, Lochtefeld explains that it was “political in the larger sense” as it was not just limited to the views of different organisations or parties but also carried larger socio-cultural messages. During the 1930 mela, for instance, the British government spread knowledge about the Sarda Marriage Act (1929) that penalised the marriage of girls below the age of 14 and boys under 16.

As recently as 1998, recalls Lochtefeld, he came across an old man carrying around anti-dowry signs during the ascetic processions at the Kumbh Mela in Haridwar. In the same mela, he also came across booths spreading information on agriculture as well as street plays promoting vaccinations for children. The Kumbh, he suggests, has been a theatre for social change. “If there is any group trying to seek recognition, or any problem that deserves attention, Kumbh provides an opportunity to engage with a large audience,” Lochtefeld says

Further reading:

James G. Lochtefeld, The Construction of the Kumbh Mela, South Asian Popular Culture, 2004

Amrit snan, 1930-2025

95 years apart, 2 melas with a lot in common

________________________________________

Coming full circle after a gap of 95 years, all the three ‘amrit snans’ (formerly ‘shahi snans’) organised in 1930 and 2025 Kumbh Mela have occurred on the same dates and days. Records with National Archives of India reveal the three special bathing days of Makar Sankranti, Mauni Amavasya and Basant Panchami took place on Jan 14 (Tuesday), Jan 29 (Wednesday) and Feb 3 (Monday), respectively, in 2025 Kumbh after a gap of 95 years, reports Shalabh. In 1930, the mela lasted a month, from Jan 14 and Feb 13, which was attended by an estimated 2.1 crore devotees. Tragedy had struck on Mauni Amavasya day in 1930 when an elephant ran amok for 20 minutes killing several people before halting in the Yamuna.

Vedic scholar and a faculty member at the Luck

now University, Shyamlesh Kumar Tiwari said: “What is seen as a coincidence can be described as an interesting concept of time called ‘Kaalchakra’. Events keep recurring in the cosmology as per ‘chaturyuga’.”

Administrative arrangements

Kumbh area is UP’s 76th district, for 4 months

UP govt has declared Maha Kumbh area in Prayagraj as anew district for four months — from Dec 1 to March 31, 2025. The decision has been made to streamline the management and administration of the upcoming Kumbh Mela, ensuring smooth operations for the grand religious event that begins on Jan 13. The newly formed districtwill be known as MahaKumbh Mela. TNN

Maha Kumbh Administrative expenditures: 1882-2024

Rajiv Mani, Dec 27, 2024: The Times of India

PRAYAGRAJ: Even as the city is all set to host the biggest-ever Maha Kumbh with an approximate expenditure of Rs 7,500 crore and expected footfall of 40 crore devotees, TOI has scanned the archives to find out how this confluence of faith has grown through the past century.The archives show that during the 1882 Maha Kumbh, about 8 lakh bathed on Mauni Amavasya, the biggest bath days, when unified India's population was 22.5 crore. The expenditure was Rs 20,288 (equivalent to Rs 3.65 crore today). The 1894 event saw about 10 lakh participants from a population of 23 crore, with an expenditure of Rs 69,427 (approximately Rs 10.5 crore in current value).

The 1906 Kumbh attracted about 25 lakh participants, with an expenditure of Rs 90,000 (at present valued at Rs 13.5 crore) when the population was 24 crore. Similarly, during the 1918 Maha Kumbh, about 30 lakh took holy dip in Sangam, with the population at 25.20 crore. The administration allocated Rs 1.37 lakh (equivalent to Rs 16.44 crore today).

The documents also contain complete details of the arrangements done by the British govt.

According to historian Prof Yogeshwar Tiwari, a notable incident occurred during the 1942 Kumbh when the then Viceroy and Governor General of India Lord Linlithgow visited the city with Mahamana Pt Madan Mohan Malaviya.

"The viceroy was astonished to see lakhs of people from different parts of the country in different costumes in the Kumbh area, taking a bath in Sangam and engrossed in religious activities. When he enquired about publicity costs, Mahamana replied, just two paise. He explained by showing the 'Panchang' (almanac), saying, this almanac comes for two paisa," said Tiwari.

Mahamana clarified that the almanac informed devotees nationwide about festival dates. Hindu tradition ensured awareness of each festival's significance and location, naturally drawing pilgrims without formal publicity or invitations.

As Prof Tiwari recounts, Mahamana told the Viceroy, "This is not a crowd. This is a confluence of devotees who have unwavering faith in religion and God. This infuses devotion in the devotees. The Viceroy, impressed by this explanation, showed respect to the Kumbh devotees.”

Missing persons

2019: 1,000 lost pilgrims a day

Sitting in a corner of the ‘Bhoole Bhatke Shivir’, 72-year-old Vindhyawati’s eyes scan the entrance to the tent every few minutes. The resident of Satna in Madhya Pradesh had been looking forward to her pilgrimage to the Kumbh Mela for years, but on that day, February 8, she was separated from her family among the millions assembled on the Ganga’s banks for the largest such gathering in the world.

‘Separated and lost at the Kumbh Mela’ is a recurring, much-referenced and even fond trope of Indian popular culture, including Hindi movies, which in the 1970s used to have entire plots revolving around it. But for pilgrims who actually get lost in the thronging crowds, ranging from the very young to the old and infirm, it is a traumatic experience. The people who man the Bhoole Bhatke Shivir now have technology to help them re-unite families.

A pilgrim was kind enough to bring Vindhyawati to the tent. In a state of shock, the old woman had hardly spoken to anyone at the camp as she kept looking for her kin for two whole days, worried that she might never see them again.

On Sunday that she heaved a sigh of relief when she saw her family members’ faces on a smartphone screen via a video call after a volunteer traced their contact number. Later during the day, a police team accompanied Vindhyawati to Satna.

Camps like Bhoole Bhatke Shivir are run using carefully-maintained manual records, but computerization is also helping. At computerized centres, volunteers keep updating details of lost people, which are then displayed prominently on screens across.

The task is massive: by February 10, the day of the third and last Shahi Snan of Kumbh 2019, volunteers managed to reunite over 24,000 people with their families, according to senior superintendent of police (Kumbh) KP Singh. By then, 14 crore pilgrims had taken part in the holy dip at the Ganga from the day the Mela began on January 15. Which means on any average day, more than 1,000 pilgrims go missing or are separated from their groups.

“We have set up 15 special police teams to take lost persons back to their native states if their fellow pilgrims have already left. This time, we sent 72 people back home. We traced their families after compiling information through various means including biometric details,” SSP Singh said.

Computerized lost-and-found camps was first introduced during the 2013 Mahakumbh, while the traditional camps have been operational since 1946.

In the 2013 Mahakumbh alone over 42,000 lost people were reunited with their families, while the Mela saw 16 crore pilgrims participating. In the 2007 Ardh Kumbh, over 23,000 people were similarly reunited.

Organiser of Bhoole Bhatke Shivir, Umesh Tiwari said, “Once inside our camps, volunteers offer lost pilgrims food and blankets.It could take days to find their families.”

Murals

2018

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

See pictures:

Streets come alive with art in Prayagraj .jpg|Streets come alive with art in Prayagraj

A priest outside a temple at Ram ghat.jpg|A priest outside a temple at Ram ghat

Hanuman adorns a wall.jpg|Hanuman adorns a wall

Trees never looked as colourful...

4 major art spots in Prayagraj

Sculpted figures being put up to create a mythological theme for Kumbh

Gods watch over all...

High-rises too get a splash of colour

Flyovers get a makeover in vibrant colours

Gods watch over all...

Art, life and spirituality converge at Kumbh

Quality of water

2025

Kushagra Dixit, Feb 21, 2025: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The Sangam waters where millions of devotees have been taking a holy dip every day during the ongoing Maha Kumbh has been found to be contaminated with alarming levels of faecal and total coliform, prompting National Green Tribunal (NGT) to summon UP govt authorities.

A quality assessment report submitted to NGT by Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) on Feb 3 said the coliform levels - a key indicator of the presence of untreated sewage and human and animal excreta - were found to be 1,400 times the standards in the Ganga and 660 times in the Yamuna at some stretches on a particular day, making the river waters unfit for bathing.

According to CPCB standards, for organised outdoor bathing, the total coliform levels must not exceed 500 MPN (Most Probable Number) per 100ml. However, CPCB found that by Jan 19, total coliform levels had reached a whopping 700,000 MPN/100ml in the Ganga and 330,000 MPN/100ml in the Yamuna. It analysed the samples on Jan 12, 13, 14, 15 and 19, and the total coliform levels never met standards.

CPCB findings not only indicated non-compliance with NGT's earlier directive to maintain critical water quality standards, but also raised concerns over public health and environmental sustainability, the tribunal's principal bench, headed by its chairperson Justice Prakash Shirvastava, noted during a hearing on Feb 17.

The high levels of faecal bacteria in the waters pose significant risks of waterborne diseases, while excessive organic pollution threatens aquatic life and overall river health.

Pointing out that UP Pollution Control Board (UPPCB) had not filed any comprehensive action taken report, as directed by tribunal in Dec last year, the bench ordered the board's member secretary and the state authority responsible for maintaining water quality in river Ganga at Prayagraj to appear before it virtually during the next hearing on Feb 19.

NGT had in Dec asked CPCB and UPPCB to monitor and report the water quality regularly, while also ensuring that untreated sewage did not flow into the two rivers so that the pilgrims who came for a holy bath did not suffer. It directed the agencies to analyse water samples from the rivers at least twice a week at regular intervals.

In compliance, CPCB submitted its report, which said river water quality did not conform to the bathing criteria at all the monitored locations on various occasions.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2018

Administration

Vegetarian, teetotaller, non-smoking policemen wanted: 2018

Wanted: Men — young, energetic, vegetarian, teetotaller, non-smoker and soft-spoken. This is no matrimonial advertisement, but the qualities the Kumbh Mela administration is looking for in policemen to be deployed during the Mela in Allahabad, starting January 15, 2019.

This apart, the policemen should also have “certified good character” clearances from their seniors. The department has also decided no police official on duty during the Kumbh should belong to Allahabad.

Deployment of security will start by October. More than 10,000 men in uniform, including paramilitary personnel, are expected to be on duty during the Kumbh.

An age limit has been set for various ranks — constables to be assigned duties should be below age 35, head constables below 40 and subinspectors and inspectors below 45 years.

DIG/SSP (Kumbh) K P Singh, said, “We’ve written to the SSPs of Bareilly, Badaun, Shahjahanpur and Pilibhit to verify the character of policemen who have applied for the Mela duty as the department seeks only vegetarian, non-smoking, non-drinking and soft-spoken policemen for the period.”

Starting October 10, police will be assigned duties in four phases. Around 10% will be deployed in the first phase, Singh said, and 40% in the second phase in November. In phases three and four, 25% of paramilitary forces will be deployed in December.

The DIG added that he has written to SSPs to interview policemen personally as officials for the second, third and fourth phases will be coming from western and other parts of the state.

2019

Administrative arrangements

Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 5, 2019: The Times of India

Area and number of visitors

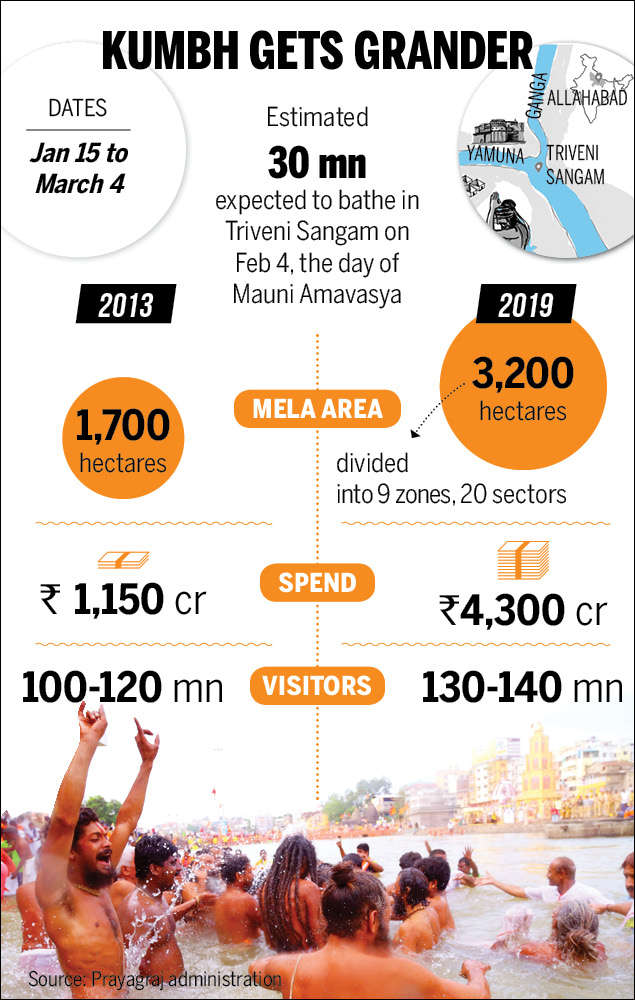

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 5, 2019: The Times of India

From January 15 to March 4, an estimated 130-140 million pilgrims and tourists are expected to do the same during the Kumbh Mela. For the devout, a holy dip will rid them of their sins, free them from the cycle of life and death.

The term Kumbh is contested. Some insist that the 2019 event is Ardh Kumbh, in accordance with the traditional alternating cycle of Kumbh and Ardh Kumbh every six years. But last year Yogi Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh government rechristened Ardh Kumbh as Kumbh. Kumbh, henceforth, will officially be known as Mahakumbh. Interestingly, Modi described the event as “Ardh Kumbh” in a December 16 speech in the city.

Renaming is the flavour of the season; till last month, Allahabad was the town’s official name. The renaming, especially of the festival, is argued even at the Sangam ghat.

But there’s unanimity that the scale of arrangements is unprecedented. In 2013, the mela was spread over 1,700 hectares; this time it is 3,200. The budget for Kumbh 2019 is Rs 4,300 crore; as per reports, it was about a third in 2013. “ Jo na 2001 mein hua, na 2013 mein hua, aisi vyavastha dekhne ko mil rahi hai (The arrangement is more than 2001 or 2013),” says boatman Ramesh Nishad, referring to the street lights and toilets in the area.

The arrangements were still a work in progress, though. Last Sunday, tractors purposefully carried tons of black sand at Sangam. And one saw hundreds of commodes waiting to be fitted in the mela area.

For the government, sanitation seems to be a key area. Dozens of health department workers in maroon jackets keenly collect any piece of paper or plastic lying about. “In all, 1,22,500 toilets, including 20,000 septic tank toilets, are being laid out,” says AP Paliwal, additional director for health and sanitation (mela).” He talks about an elaborate mechanised system of compactors and tippers for solid waste management. “We don’t want a single drop of sewage to pollute the river.” A special medical unit to track and avert possible break-outs of epidemics has been set up.

Using drones for surveillance, carrying out mock anti-terror drills and setting up an integrated command and control centre with 1,100 cameras for real-time feed — the BJP government seems keen to project Kumbh as a safe and efficiently-managed, high-tech event. Digital screens across the city show films on Kumbh day and night. On social media — Facebook, Twitter and Instagram — the campaign is relentless. The returns, though, are modest. The official Kumbh handle has 8,500 followers while Facebook’s official Kumbh page has 37,000 likes.

Social scientist Archana Singh says the administration has taken a techonological leap in providing traffic information on Google maps and signage in satellite town parking and mobile app, to facilitate pilgrims. “But to enjoy these facilities you need a smartphone. They seem to have overlooked the fact that an overwhelming majority of pilgrims come from rural, technology-challenged backgrounds,” she says.

Singh’s team provides inputs to the local police to improve its efficiency. Arranging e-rickshaws for the physically challenged and having volunteers who speak different languages and dialects to assist the police are among the suggestions provided by them. “We have also organised workshops for police with special emphasis on gender sensitisation,” Singh says.

Outside the mela area, the rest of the city is also getting ready for Kumbh. Broken pavements have either been or are being repaired and upgraded. Road dividers are bringing order to traffic. “Nine railway overbridges have been constructed in and around the city. Six underbridges have been widened,” says Ashish Kumar Goyal, commissioner, Allahabad. He adds, “More than half of the Kumbh budget is for the city’s permanent works.”

For a city that seemed to have regressed with time, infrastructure projects have been fast-tracked due to the Kumbh. “Earlier, Allahabad had an airstrip. Now it has a full-fledged terminal,” Goyal says. PM Modi inaugurated the new terminal last month. SpiceJet will begin a daily flight from Delhi on January 6.

Illegal encroachments, some several decades old, have been removed. Trees, even older, have been felled. About 300 murals have transformed the city into a flamboyant open-air art gallery even though there’s near-amnesia on the city’s Mughal and British past.

There is a flip side to the city’s recasting. Dust hangs over Prayagraj like a thin film of brown smoke. “You would have never seen so many people wearing pollution masks in Allahabad as today,” says Singh.

Social scientist Badri Narayan says there was a need to distinguish between the well-heeled encroacher who expanded his house illegally from the urban poor: the tea sellers, the hawkers. “The administration could have been more sympathetic towards them. Development must have a human face,” says Narayan, who’s the director of Gobind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute.

But Goyal has a different take. He says that even places of worship were shifted by taking locals into confidence. “We have got tremendous public support for removal of encroachments,” he says. Novelist Neelum Saran Gour points out that a Mughal doorway near Khusro Bagh was pulled down. “That could have been avoided,” she says. But adds, “I am optimistic that we will find a better city at the end of it.”

Kumbh is boom time for many small traders and hawkers. The city’s 600-odd boatmen are also expecting a major jump in their income. Boatman Rishi Nishad said: “On an average we earn Rs 300 to Rs 800 per day. During Kumbh, we are expecting to at least triple our income. Not only because of the number of visitors, but also rates will double due to high demand.” Priest Dinesh Pandey also expects a similar raise in his earnings during the seven-week festival.

Many small hawkers are worried, though, that they won’t be able to set up their stalls. Sunil Kumar, who peddles cheap hosiery for a living, says his shop was shifted two km away. He is worried that he might be forced to shift again. “ Chhoti pheriwalon ko bahut pareshaniyan hai (There are lots of problems for small hawkers),” he says.

Not all problems have been resolved yet. But the UP government is working overtime to make the holy festival a success. “We are in the process of applying for three Guinness records in the areas of cleanliness and transport and for the ‘Paint My City’ campaign,” says Goyal.

For most pilgrims, however, the Kumbh has one simple meaning. As a couplet on one of the banners says, “ Anya teerthon mein gyaan, aur Prayag mein moksha ka snan (In other holy places you get knowledge / In Prayag, you get the bath of salvation).

The three shahi snans and Mahashivaratri

The 49-day Kumbh mela drew to a close at the Sangam notching up three world records in the Guinness Book and a footfall of 24 crore people. On Monday, over 1crore faithful took the holy dip on Mahashivaratri, the last of the ‘snans’ that started on January 15.

The Prayagraj Mela Authority secured three world records: over 7,600 people came together to create the world’s fastest handprint painting in eight hours, it mobilized 10,000 individuals to sweep multiple venues at five locations in a single day, and paraded the largest number of buses in the world, a fleet of 503 running a length of 3.2km.

Officials said around 45% of devotees took a dip at the three shahi snans — 2.25 crore at Makar Sankranti on January 15, more than 5.5 crore at Mauni Amavasya on February 4 and 2 crore on Basant Panchami on February 10.

UP minister of state (independent charge) Suresh Kumar Rana said, “The Kumbh Mela hosted delegates from 192 countries.”

An Italian national at the Kumbh, Alasendaro, said, “The atmosphere is rustic yet replete with spirituality and energy. It’s a great experience and can be felt only through physical experience.”

The Kumbh will be officially declared closed on Tuesday by UP CM Yogi Adityanath.

2025

Wholesale hub shut due to Kumbh, medical crisis in Prayagraj

Kapil Dixit, February 21, 2025: The Times of India

PRAYAGRAJ: With the rush of devotees for Maha Kumbh leading to 'unofficial' closure of the wholesale medicine market in Prayagraj, the city is facing a crisis of medicines, including life-saving drugs, but the authorities have so far ignored the SOS messages from traders.

Leader Road, which happens to be the wholesale medicines hub, falls on the busiest path from Sangam towards the railway station. Therefore, the entry of trucks carrying supplies is prohibited and since mid-Jan, the market has been unable to operate properly due to the unabated flow of devotees. As a result, the medicine stocks, especially of BP, heart diseases and diabetes, are nearly exhausted at both wholesalers and retailers.

Anil Dubey, who heads the Allahabad chemist and druggist association, told TOI, "Since Jan 24, traders in the wholesale drug business have not been able to operate their business properly, which has led to a huge gap between demand and supply."

Traders complained the supply chain had been hit as trucks carrying even drugs are not allowed to enter the city limits. "Association members have made several attempts to convey the shortage of drugs to the district authorities concerned, but in vain," Dubey said. No transporter is ready to book medicine consignments to Leader Road due to the strict measures of police and district authorities, he added.

Govt authorities, however, shrugged off the crisis and said there was no official order for the closure of the market.